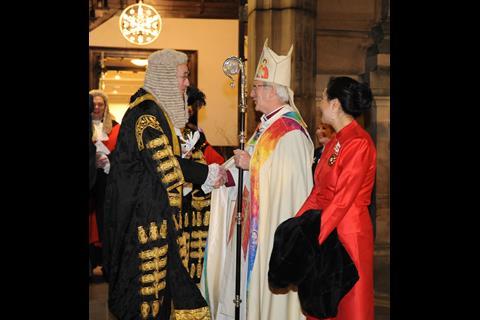

Birmingham lawyers filled the city’s cathedral on Thursday evening for a service to mark 200 years since the formation of the Birmingham Law Society.

In a service and reception that mixed civic and ecclesiastical pomp with good humour, Birmingham’s lawyers pledged ‘to work with all our hearts, and all our minds, and all our strength for the good of [the county’s] people and the well-being of its society’.

The Birmingham society, a professional body older than Chancery Lane, was set up on 3 January 1818 by 19 lawyers at Temple Row – an area that remains the heart of Birmingham’s legal community. The society now has 4,500 members, including 1,000 who joined in the past three years.

Birmingham has long been home to leading national firms such as Pinsent Masons, Eversheds Sutherland, Gowling WLG and Mills & Reeve, and in recent years has welcomed a substantial in-house legal team from Deutsche Bank and a Hogan Lovells office. Prime office space on Snow Hill has allowed the legal community to expand close to Birmingham’s legal heart.

What has changed in 200 years? Presiding over the service, the Very Reverend Matt Thompson noted that the BBC now referred to the lord chancellor as ‘a middle-ranking minister’, a source of concern to many present - though Thompson quipped that, in his world, a middle-ranking minister meant ‘after Canterbury, but before York’.

Appeal Court judge Sir Andrew McFarlane, a Birmingham law student 45 years ago whose early practise was in the city, said a failure to respect lawyers and the law meant there was ‘a risk of the constitution becoming eroded’.

He cited headlines following judgment in Gina Miller’s ‘Brexit’ case, where judges were labelled ‘Enemies of the People’ (Daily Mail), while The Telegraph portrayed the case as ‘Judges v The People’.

Yet people needed rules and wanted them fairly applied, Sir Andrew noted. As one of the judges ruling on the occupation of the area around St Paul’s by the Occupy movement, he observed: ‘It is not often as a judge that you get to encounter and interact with a group of anarchists. What astonished [me] was that almost from day one [at St Paul’s], the anarchists organised their lives according to strict rules. They had their own “police force’, called “prefects”, and someone breaking the rules might be expelled from the site.’

‘In a complex and sophisticated world,’ he added, ‘it is important for individuals and companies to know where they stand.’ In that, lawyers should celebrate the good that they do.

1 Reader's comment