The feeding frenzy surrounding NFTs highlights the legal and regulatory challenges that the rapidly emerging world of cryptoassets brings – and lawyers will have their work cut out

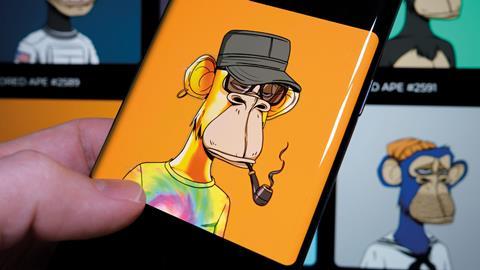

The hottest business trend on the internet at the moment has sprung from the discovery that people will pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for unique strings of digital code known as ‘non-fungible tokens’ (NFTs). Late last year one such token, created on the Ethereum blockchain and depicting a cartoon ‘bored ape’, sold for $3.7m at Sotheby’s.

Not surprisingly, the market in cryptoassets, of which NFTs are one form, is full of potential legal pitfalls. Latest guidance on the topic published last week calls for urgent action on the part of the government ‘to clarify its policy approach and introduce new rules where relevant’ in order to create efficient and orderly markets in cryptoassets.

Such digital tokens are but one topic covered in the new, second edition of Blockchain: legal and regulatory guidance, drawn up by expert group Tech London Advocates and made available on the Law Society’s website. The 230-page guidance covers the whole range of products and services made possible by developments in cryptography, the best known of which is the Bitcoin system of digital coinage. Other innovations include ‘smart’ self-executing contracts and digital coins issued by central banks – including, potentially, the Bank of England.

'Every lawyer will require familiarity with the blockchain, smart legal contracts and cryptoassets – both conceptually and functionally'

Sir Geoffrey Vos, master of the rolls

All these raise significant legal and regulatory issues in fields ranging from data protection and security, to money laundering, gambling, intellectual property, standards of dispute resolution and environmental harm.

The sector is extraordinarily new: the first NFTs, for example, were coined in 2018. But at a time when 2.3 million Britons are estimated to have invested in digital coinage, awareness of these issues can no longer be confined to niche crypto specialists. Introducing the guidance, master of the rolls Sir Geoffrey Vos pointed to three imminent developments that will bring blockchain-based systems into the mainstream. They are: the launch of central bank digital currencies; the widespread adoption of digital transferable documentation; and the transition to ‘smart’ documents. ‘They will mean that every lawyer will require familiarity with the blockchain, smart legal contracts and cryptoassets – both conceptually and functionally,’ he said.

The ability of existing laws and regulatory structures to accommodate these developments varies. Studies by the UK Jurisdiction Taskforce and the Law Commission have concluded that smart legal contracts can be valid in England and Wales, and that disputes arising from them will be of types familiar to our courts. Existing legal concepts can be tweaked – as there can be no such thing as a ‘reasonable computer’, the term ‘reasonable coder’ is likely to enter our vocabulary.

Digital assets may be a trickier proposition, and not just because of the current market frenzy, frequently likened to 17th-century ‘tulip mania’. As the guidance notes in its section on NFTs: ‘It is often unclear what rights the purchase of an NFT gives to the purchaser.’ Such questions are currently exercising the Law Commission, which is expected to publish proposals for a legal regime covering cryptoassets this summer. Speaking at a seminar to launch the expert guidance this week, law commissioner Professor Sarah Green noted that cryptoassets do not fall easily into existing categories of legal ‘things’ – a new third category may be required to sit alongside those of ‘chose in possession’ and ‘chose in action’.

But if all this implies that reputable lawyers should not be touching cryptoassets with a bargepole, solicitor Tom Grogan, chief executive of London firm Mishcon de Reya’s digital transformation arm MDRxTECH, presented a more upbeat view. He likened the current crypto-scene to the state of the worldwide web 25 years ago, before governments and big business took it seriously. ‘In 1996 the internet had just come out of the basement,’ Grogan said. But this was where the innovation happened: ‘It was where people broke things.’

That is all very well, Sir Geoffrey commented, but today in blockchain there is a massive gap between the back alley and the mainstream. The big question is how to jump the crypto world from 1996 to ‘somewhere more like 2006’ – especially in the eyes of his more sceptical judicial colleagues.

Grogan suggested that this will be driven by ‘use-cases’ – products and services that are adopted for their own sake and not because they incorporate specific technologies. But first, we need leadership and a sound legal framework. Optimistically, the guidance says that the UK ‘has an opportunity to develop an effective and proportionate regulatory regime for cryptoassets’.

To get there, lawmakers will need to be nimble. The latest guidance updates the 2020 first edition. Anne Rose, co-lead of the working group, said that updates of the current edition will be needed this year. Lawyers wishing to keep up with the master of the rolls, take note.

No comments yet