The Human Rights Act is likely to be replaced by a bill of rights. Whether the case for reform is made out or not, the lord chancellor does not intend to be thwarted by hostile lawyers

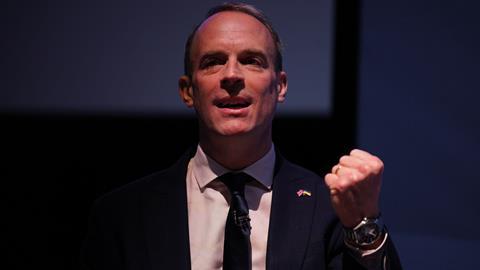

The Ministry of Justice’s consultation on human rights reform remains open (to some), and has so far been greeted with widespread opposition. But lord chancellor Dominic Raab made clear this week that the government has no intention of abandoning its proposals, which would see the Human Rights Act replaced with a bill of rights.

The Law Society says the case for reform is not made out. The lord chancellor disagrees. ‘In the end it is not solely our job to listen to legal practitioners, important as they are, or indeed to serve their interests, but also to stand up for victims and the public and make sure we have a commonsense approach to justice,’ Raab told the Commons on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, in an interview with Joshua Rozenberg for BBC Radio 4’s Law in Action this week, Raab spoke of two areas where we can expect significant changes. A couple of consultation responses that Raab has received may provide a clue on the details.

Raab told Rozenberg that the bill of rights will allow the government to strengthen ‘some of those quintessentially UK rights’ such as free speech. ‘We’re talking at the moment about oligarchs fuelling the Russian war machine, who can come here and use their deep pockets to muzzle authors, journalists, researchers and critics on modest means, using libel laws and the costs regime that applies, and it’s happened notwithstanding the Human Rights Act.’ His aim is to protect free speech from ‘creeping judicial-made privacy law’.

This concern is shared by the Society of Editors, which was invited to attend a roundtable discussion with justice minister Lord Wolfson earlier this month. ‘While the society recognises the need for privacy rights in society and that freedom of expression is not an absolute right, we have seen section 12(4) of the Human Rights Act significantly weakened over the years by the emerging development of the tort of misuse of private information,’ its consultation response states.

'In the end it is not solely our job to listen to legal practitioners, important as they are, or indeed to serve their interests, but also to stand up for victims and the public and make sure we have a commonsense approach to justice'

Dominic Raab

The Society of Editors supports proposals submitted by Associated Newspapers Ltd, Times Newspapers Ltd, News Group Newspapers Ltd and Telegraph Media Group for the introduction of an actual or likely serious harm threshold in misuse of private information cases, and a defence of ‘reasonable belief that publication was in the public interest’.

Courts should be given specific direction on how to approach questions surrounding the public interest and journalistic activity. A higher threshold should be introduced for interim relief to restrain publication before trial than is currently achieved through section 12(3) of the Human Rights Act.

The society also supports newspaper publishers’ proposals on source protection. When considering disclosure, courts would consider the extent to which the information provided by the source relates to issues of public interest; the impact of disclosure on the journalistic source and the journalist; the potential adverse effect which such relief may have on journalistic sources more generally; and any delay by the party seeking disclosure.

When Raab first announced plans to overhaul the Human Rights Act, he said criminals had been abusing human rights for too long, too often – citing the example of a man convicted of domestic abuse claiming the right to family life to avoid deportation. He repeated the citation in his interview with Rozenberg.

Professor Richard Ekins, head of right-of-centre thinktank Policy Exchange’s Judicial Power Project, says in his consultation response that immigration and asylum legislation needs to authoritatively and expressly address the rights questions in play and make provision for how the balance is to be struck in different types of case. For instance, the extent to which it should be open to the secretary of state to order deportation if someone is at risk of maltreatment or if that person would not enjoy UK-level healthcare at home.

‘Legislation might make clear that decisions about the public interest in deportation, and about the proportionality or otherwise of a deportation, are to be made by the secretary of state and not by the court, with the court’s role limited to traditional judicial review principles,’ Ekins adds.

‘The answer then is careful specification of the rights in question in the bill of rights, if such is to be enacted, and careful drafting in immigration and asylum legislation, which makes clear that the latter legislation is parliament’s specific decision on point.’

It appears that, unless the government performs a spectacular U-turn, a bill of rights is coming. Legal practitioners must prepare to drill down into the details.

2 Readers' comments