The young bar is debt-ridden and stressed out while senior barristers are nervously contemplating digital justice. Max Walters reports from the Bar Conference.

The Bar Conference on 15 October took place in the long shadow cast by the £1bn Transforming Justice initiative unveiled last month – and proselytisers from the senior judiciary were on hand to spread the word.

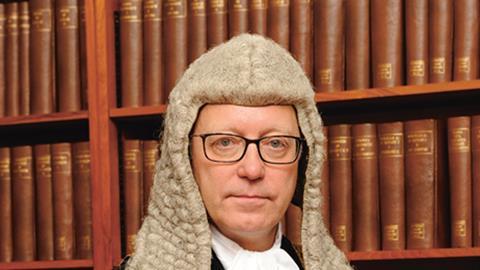

Online dispute resolution will ‘become the norm’ in less complex civil, family and tribunals cases, senior president of tribunals Sir Ernest Ryder (pictured) said in a plenary address.

Ryder said the next few years will see the biggest changes to the justice system since the 1870s – but stressed that access must remain paramount.

He denied the government’s austerity agenda was the driver of reform, arguing that this approach ‘runs the risk of price rationing, the antithesis of equal or fair access to justice’. However, he did concede austerity has ‘forced us to face up to the system’s limitations’.

He added: ‘We must address lengthy delays that are inimical to justice and to welfare, processes and language that are unintelligible to all but the specialist user and a system that is at times so costly the only solution so far has been to impair access to justice by removing legal representation.’

Ryder said the aim is to create a 21st-century environment ‘where paper-based processes are to digital processes and cloud-based systems what the horse-drawn carriage is to space travel’.

Lord Justice Briggs, architect of the new online system, took up the thread at a panel session hosted by the Chancery Bar Association on ‘the changing landscape’.

The ‘sky’s the limit’ for online court claims, Briggs declared, adding that the £25,000 threshold in a new online court for dealing with monetary claims could be increased if it proves to be a success.

Briggs, whose final report on the future of civil courts was published in July, said it was a case of ‘suck it and see’ and that ‘if it works it [the maximum level for claims] could grow’.

Briggs has attracted flak for his insistence that the online court needs ‘minimal assistance’ from lawyers, but acknowledged there would be instances where input from lawyers would prove useful.

This could be a ‘decisive issue of fact’ that turns on oral evidence where the answer is not apparent from documents, he said.

He said there are ‘lots of cases’ where that is true and where ‘at least that part of the trial should be dealt with face to face’.

The online court will include a three-stage process, an automated triage to decide on the merits of a case, arbitration handled by an assigned case officer and a judicial decision if the case cannot be resolved any other way.

When he launched the report, Briggs acknowledged that some would be ‘critical, sceptical or fearful’ of the concept, with the concern that users will be denied justice, the exclusion of lawyers will affect the outcome, or that £25,000 is too high a threshold.

In a separate session on the future of digital courts, Fiona Rutherford, deputy director of business strategy at HM Courts & Tribunals Service, said ‘difficult decisions would lie ahead’ when assessing the department’s estate.

‘Disposal of buildings will enable future funding and in the future we will be less reliant on our estate’, she told delegates.

Senior Presiding Judge Sir Adrian Fulford said ‘seismic changes’ are coming thick and fast and that ‘we must adapt’ to changes in technology.

He predicted that work across all courts and tribunals could be transferred to the ‘cloud’ within the next four years.

‘There will be no more running after brief papers that are stuck in the back of somebody else’s car,’ he said.

‘We have to change; if we don’t we will get left behind. Judges who vowed never to touch a keyboard are now working entirely digitally.’

In her keynote address, bar chair Chantal-Aimée Doerries stressed that while the profession supports the idea of ‘widening access’, this has been eroded by cuts to social welfare and legal aid.

Citing statistics from the Ministry of Justice which showed that one-third of cases in the family court had no legal representative for either party, she called for a full review of the effects of legal aid cuts, which should be carried out ‘as a matter of urgency’.

Doerries added that despite criticism, a barrister’s role is at the ‘heart of the justice system’. Barristers are ‘not mere economic actors’, acting in the interests of consumers, but also serve the public interest as ‘part of the glue that holds society together’.

‘Despite challenges, we will continue to survive and thrive,’ she said. The profession ‘should not expect to be popular’ but should at least be valued.

Doerries also announced the launch of a ‘wellbeing portal’ – an online service aimed at supporting barristers and encouraging them to address their professional and personal concerns. This follows a ‘Research into Wellbeing’ survey undertaken in 2014 that surveyed 2,500 barristers.

According to Doerries, one in three respondents found it difficult to stop worrying, two in three felt showing signs of stress amounts to weakness and one in six felt low in spirits ‘most of the time’.

Louisa Nye, chair of the young bar, said the younger members of the profession in particular are living in ‘deeply uncertain times’.

She said the costs of qualification leave many newly qualified barristers nursing debts of between £30,000 and £70,000, and they were also demoralised by ‘almost daily’ attacks characterising lawyers as a ‘scourge on society’.

‘Barristers are not a scourge on society. Advocates ensure people’s rights are protected. I call on [HMCTS] and judges to continue to take advice from us as technology changes how the courts operate,’ she said.

The bar regulator, meanwhile, is reporting ‘encouraging’ interest in alternative business structures, which it expects to begin licensing imminently.

But the organisation is cautious about going toe to toe with the Solicitors Regulation Authority to attract registrants, amid fears of race-to-the-bottom regulatory arbitrage.

The Bar Standards Board was approved as a licensing body for ABSs in March but is awaiting parliament’s rubber stamp.

Director general Dr Vanessa Davies told the conference licensing is ‘weeks away’, with the body this month completing an external ABS pilot project which raised ‘no major issues’.

In the last 18 months the BSB has licensed 65 ‘entities’ – bodies owned and managed by lawyers. However, initial interest came mainly from single-person operations looking to exploit tax advantages that have now largely disappeared.

More recently, said head of supervision and authorisation Cliodhna Judge, the profile of new bar entities has become larger and more sophisticated.

Asked if the bar regulator will compete with the SRA for ABS business through cheaper fees, Davies was equivocal.

She pointed out that the BSB’s policy on the businesses it will regulate is more tightly drawn, being based on the ‘traditional services’ offered by the bar. Differences relating to client money and indemnity insurance also distort the playing field.

The board’s authorisation fees vary depending on the number of individuals practising through the entity.

4 Readers' comments