Michael Simmons’ central London practice appears buoyant, most recently acquiring a four-partner firm near Lincoln’s Inn. But his ambitions are increasingly thwarted as dissident partners get the upper hand...

After the deal for CH & Co was completed, I discovered that one of their partners was going on holiday to Los Angeles. ‘You must go and see David S, my lawyer friend there,’ I said to him.

‘But I’m on holiday,’ he replied plaintively.

I had made it a rule always to contact the local lawyers wherever I went and this had been passed on to all lawyers in the firm.

Philosophically, I was trying gradually to change from an autocrat to a democrat in the way I ran the firm. Over 26 years, my equity stake gradually came down from 100% to 6%.

I was probably deluding myself into thinking that I was making the transition seamlessly, but I was trying hard. Now I found it time-consuming and frustrating that I could no longer make split-second decisions, but had to spend valuable time taking soundings and trying to persuade others to my point of view. In this, I was increasingly failing.

There were two main issues which concerned me. The first was related to the type and quality of the work that we undertook. I felt that we had come a long way and I wanted to attract the best lawyers to join us.

This meant that we had to have the right work to keep them interested. Other partners were now also bringing in work and I was concerned that much of it was of the wrong type: quantity was becoming a substitute for quality.

For example, we were getting multiple instructions from first-time buyers on large estates. I would much have preferred to be acting for the developers, which could have been challenging work. What we were doing was boring, undemanding and unchallenging. It demanded lawyers of the lowest calibre, as this type of commodity work paid low fees and in no way justified the overheads of a central London office. I was reminded of the story about subeditors at The Times who were all supposed to be unfrocked clergymen, had a separate entrance and were not allowed to mix with the other staff.

We talked about farming out this work to a suburban branch where overheads would be lower, but it remained a subject for discussion rather than action. As a result, we became stuffed with low-calibre lawyers. Inevitably, if they stuck around long enough, they would be elevated to the partnership with damaging results. I was a lone voice in my objections. The others all seemed perfectly content for the currency to be devalued.

My other complaint was about the balance of the work we undertook. I viewed our law firm as a department store where the departments gained or lost in importance depending on the cycles of the economy. Thus, in a boom, the property department would be bringing in the big fees, while in the inevitable bust that followed, the litigation department was our salvation.

'The truth of the matter was that after 25 years of running the firm, I was burned out. I could not see it myself and I had nobody to tell me. If I’d had some sort of mentor, I wonder if I would have listened to them. I needed a sabbatical but felt in no position to take one'

In addition to those two departments, which we were maintaining roughly in balance, I felt it essential that we had an especially strong company and commercial department. This was the justification for paying central London overheads, as the work carried the highest fees.

I had recruited John G, who was an excellent company and commercial lawyer to the point that I passed on my work of that type to him. John would never be a big source of new clients but he was excellent at keeping those assigned to him.

I expected that he would recruit other like-minded lawyers and gradually build up the department to match and rival the other two. I was disappointed. Apart from John himself, the department never grew as I wanted.

I introduced Tony V as an additional corporate partner. Tony had the personality to attract clients and I was hopeful that he would prove the catalyst. But John and Tony did not prove a happy match and the latter soon left to join a better firm than ours, where he remained a top corporate partner for the rest of his career. We still remain friends. I now think that our loss was due to John’s insecurity, but I found it very frustrating at the time.

I had at least relieved my burden considerably in terms of day-to-day management. I had decided to split the role, following the corporate model into executive chairman or senior partner and chief executive.

None of the existing partners had the desire or aptitude to be managing partner. I considered trying to import a managing partner from another firm, but I did not see how it would fit culturally. I therefore decided to recruit the equivalent of a managing director from outside the legal profession.

One problem was that I had only the vaguest idea of what qualities I was looking for and what the work entailed. So I used the first tentative interviews to define what I was seeking.

If it were possible, I should probably apologise to all those whose time I wasted in the search. I interviewed ex-military types who were running golf clubs and accountants in charge of every conceivable enterprise. I suddenly found that the people who made the most sense to me were those who had been running their own businesses which had nothing to do with the law at all.

Eventually, I settled on Max R, a small and pugnacious Liverpudlian who had run his own electronics business, albeit ultimately without success. I felt comfortable with him and that he would easily translate into our very different world.

Surprisingly, my partners seemed indifferent to the whole process, although I did try to involve them. It was as if they existed in a parallel universe and the governance of the firm was of no concern to them.

By contrast, partners meetings, which I of course chaired, were getting longer and longer. A couple of partners with particularly booming voices seemed to seize control of the agenda, not that their interventions led anywhere practical. There was an increasing divide between the business and the professional sides of the firm; the other partners were only interested in the latter.

On the face of it, I was in an enviable position. I was senior partner of a fast-growing, middle-ranking and profitable law firm. But I was becoming increasingly unhappy. In the old days, I couldn’t wait to get to work to start solving the problems of the day. Now, I found it increasingly difficult to drag myself to enter what I was finding a hostile atmosphere.

Working with Max started out well and I felt that he was my man. However, some partners whom I was increasingly considering as dissidents were spending more time with him and I was finding him less accommodating to my ideas.

At a Christmas party for the staff and their families, I marvelled at how many people depended for their wellbeing on the partners and ultimately me getting it right. One of the brighter junior partners who had trained with us came up to me: ‘Michael, what are your ambitions?’

I found it difficult to answer. Eventually, I replied: ‘Stay out of trouble.’

The truth of the matter was that after 25 years of running the firm, I was burned out. I could not see it myself and I had nobody to tell me. If I’d had some sort of mentor, I wonder if I would have listened to them. I needed a sabbatical but felt in no position to take one.

I was approached by Waterlows, law publishers and one of the companies in Robert Maxwell’s stable. If I wrote another book on law firm management, they would like to publish it.

With more time on my hands I wanted to put together the first book on law firm mergers and takeovers. I planned to be the general editor, write on those subjects which particularly interested me and persuade others well qualified on both sides of the Atlantic to contribute their specialised knowledge.

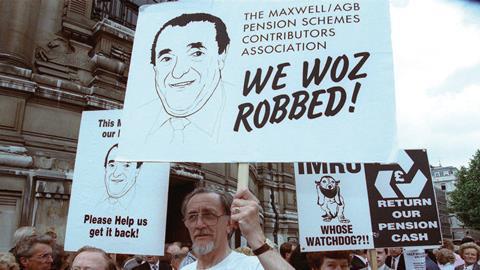

Waterlows liked the idea and assigned Kim Corker, a charming but firm editorial assistant, to see that I delivered. The book took a lot of work, particularly in chivvying others to perform on time. It was published to considerable acclaim, but unfortunately its publication coincided with Robert Maxwell going to his watery grave and the subsequent collapse of his financial empire. I never saw a penny in royalties, all of which were snatched by the insolvency practitioners winding up the company.

The book certainly burnished my credentials as a law firm consultant but I had already decided that I was on the wrong side of the Atlantic to make a living out of consultancy.

Otherwise, I had opened a small office in Jersey and established an extremely lucrative joint venture with a law firm in Hong Kong from which much excellent work was flowing in both directions. As a result, a few of us were admitted to practise in Hong Kong, though I was happy to leave work there to the lawyers on the ground. My ambition to turn us into an international law firm was some way towards fruition. New York was proving harder to crack and my efforts to set up a joint venture there came to nothing.

However, we were invited to open an office in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. After a few visits, it all came to nothing as the local economy suffered one of its regular collapses. We had even agreed to take on an English lawyer to manage the office there. I proposed that we should take him on in London as an alternative. My partners however could not think laterally, took it out of my hands and paid him substantial compensation from what I considered to be our hard-earned funds. He joined another London firm anyway to set up their construction department: another opportunity missed.

I was still battling John G to increase the size of the corporate department. I interviewed Ron N, who was the commercial partner at Janners, a firm I had always admired. Barnett Janner had been Labour MP for one of the Leicester constituencies before being made a peer and had built up an excellent law practice. His son, Greville, had been a senior boy at my school when I was very junior.

When a group of us went up to Cambridge out of term to sit the scholarship exams, we were met by Greville, who was in residence prior to taking up the post of president of the Cambridge Union. He gave us all a great time, to the point that our scholarship chances were almost jeopardised.

Greville and I remained friendly throughout our professional careers and I never had the slightest feeling that there was any grain of truth in the malicious allegations which were raised against him in his later life, and which his dementia and death prevented him from rebutting. I feel strongly that Greville was wrongly and unfairly traduced.

No comments yet