A shrinking economy and proposed changes to the profession have left Canada’s traditionally insular legal profession looking outwards for new opportunities. Marialuisa Taddia reports

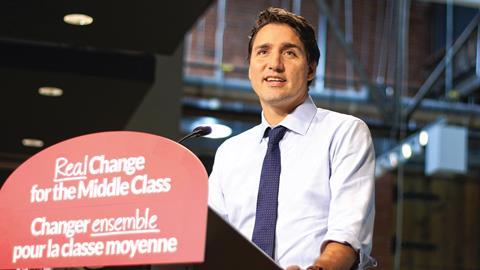

Canada’s recent general election brought a dramatic change of government, as the Liberal party came from third place to win a majority in the House of Commons.

The new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, ran on the slogan ‘real change now’. Change is also a subject on the minds of the legal community, where events are jolting the country’s law firms out of their comfort zone. Thanks to fairly conservative financial practices, Canada’s economy and banks were largely unaffected by the global financial crisis and ensuing recession. But falling oil prices since June last year have damaged the energy-exporting economy, which contracted 0.5% in the second quarter of 2015.

Aside from a difficult economy, which is hurting an already flatlining legal market, proposed changes to the legal profession could see accountants and in-house legal teams competing head-on with traditional law firms.

Reaching out beyond Canadian shores offers ‘big opportunities’, says Quentin Poole, head of international projects at Wragge Lawrence Graham & Co. ‘There are definitely risks to the larger Canadian law firms if they don’t look to internationalise their business. There has been a tendency on the part of many of the Canadian firms to be somewhat insular and orientated around Canada.’

But that is changing. There has been an increase in international mergers, and UK-based firms are playing a key role. The trend started with the 2010 tie-up between UK’s Norton Rose and Montreal-based Ogilvy Renault, and this year has been particularly busy. In April, DLA Piper joined forces with Vancouver-based Davis, while Gowling WLG is the combination, announced in July, between UK’s Wragge Lawrence Graham & Co and Ottawa-based Gowlings.

‘I would be surprised if we didn’t see any further movement [on mergers], certainly in the next two years,’ says Roderic McLauchlan, a partner in the Toronto office of Clyde & Co, which merged with boutique insurance firm Nicholl Paskell-Mede in 2011.

‘The Canadian legal market is static or even shrinking,’ says Dentons’ Canada CEO Chris Pinnington. Firms, he argues, must embrace globalisation or lose business. ‘While a mature economy, Canada is firstly a rapidly globalising economy and, increasingly, Canadian businesses are expanding their horizons, investments and activities onto the global stage.’

Dentons is the product of a three-way combination in 2013 between Canada’s Fraser Milner Casgrain (FMC), Anglo-US firm SNR Dentons and France-headquartered Salans.

Pinnington, formerly the CEO of FMC, says: ‘We recognised that our ability to follow and continue to work as trusted advisers to clients as they expanded internationally, in a context where we were at that point a standalone domestic firm, really limited our ability to fully serve [their] needs.’

Dentons’ international reach played a key role in advising China’s Minmetals on its $5.85bn acquisition of a copper mine in Peru last year. The transaction involved teams of lawyers based in Beijing and Shanghai, Vancouver and Washington DC. ‘This is a deal that legacy FMC would not have been involved in,’ Pinnington says.

Mergers and opportunities

If Canada’s business firms must go global to survive and thrive, what is encouraging English firms to venture into the US’s northern neighbour?

Stephen Denyer, head of City and international at the Law Society, says: ‘It’s principally because Canada is such a natural resource hub, but also because so many natural-resource businesses are Canadian-owned, Canadian-originated, [and] have real involvement in many important emerging markets.’

Canada holds the world’s third-largest proven oil reserves after Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. This includes the oil sands in the western province of Alberta. It is also a global leader in the production of potash, and ranks among the top-three global producers for uranium, softwood lumber, wood pulp, aluminium, platinum group metals and hydroelectricity, according to government agency Natural Resources Canada. Between 2009 and 2013, Canada’s natural resource businesses – among them Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources and Husky Energy – contributed on average about C$26bn [£13bn] per year to Canadian government coffers.

Beyond energy and natural resources, Denyer says there are opportunities for law firms in project finance and infrastructure, capital markets, international arbitration and cross-border litigation.

‘Pretty much every major London firm does business with Canada,’ he says. The more traditional route has been ‘working on a friendly basis’ with Canadian firms, while mergers are ‘a relatively recent development’. The advantage of teaming up with domestic firms is twofold: they have ‘very strong and deep client relationships’; and a network of offices across, by one measure, the world’s second-largest country, with six time zones.

Once the combination is complete in January, Gowling WLG will have over 1,400 lawyers and legal professionals in 18 locations, and a turnover of more than £400m. Gowlings, one of Canada’s biggest business law firms, brings 10 offices, including seven in Canada, and over 700 lawyers.

From a UK perspective, there were three main drivers behind the tie-up.

‘First, Gowlings has a fantastically strong range of practice areas and sectors that are very interesting to us,’ Poole says, highlighting energy, natural resources and intellectual property. He is unfazed by the steep decline in commodity prices. ‘Oil and gas in isolation is important to Gowlings, and indeed to us, but it is not overwhelmingly important. There is a whole range of other areas in energy that are resurgent.’

For example, renewables and nuclear, which is ‘starting to rear its head in a big way’, he says. ‘We have already started working with Gowlings on nuclear projects. Putting our expertise together with theirs has been terrific.’

The second driver was Canada’s cultural, historic, and linguistic links with the UK. ‘The culture fit was very strong so it makes it a bit easier if you are trying to build a global platform if you do so with a firm that is English-speaking and operates in a legal system that [is based on] English common law,’ Poole says. ‘Canadians are quite culturally aligned to the UK.’ The two firms knew each other very well, with connections going back two decades, he adds.

Third, Canada is a bridge to the US. The country is the US’s largest trading partner, ahead of Mexico and China. ‘We have about $20m a year of work which we generate from the US,’ Poole says. ‘By getting together with Gowlings, which has much more than that, obviously we can get into some of their relationships and build up from there, and therefore grow our US practice significantly.’

There is an expectation that the Canada-US connection will bring further growth. In Germany, Wragge Lawrence Graham & Co has a small IP practice in Munich and is seeking expansion through a merger. Poole says: ‘Bringing Canada to the party strengthens our position in discussions with German firms, and very relevant there is the US business which we can generate together. A good chunk of that will flow into Germany.’

Following expansion into Canada, Norton Rose moved on to form Norton Rose Fulbright by tying the knot with US firm Fulbright & Jaworski in 2013. But Gowling WLG has no such plans. ‘That is not on the agenda,’ says Poole. ‘One of the strengths of the deal with Gowlings has been to put together the US business development initiatives of the two firms and have a two-plus-two-equals-five combination. It is based on the premise of having relationships with a range of law firms and corporates in the US, rather than getting into bed with any single law firm.’

Dentons, the world’s largest firm by headcount since joining forces with with China’s Dacheng in January, has made such a move, however. In July, Dentons US merged with Atlanta-based McKenna Long & Aldridge.

‘The single largest bilateral trading relationship in the world continues to be US-Canada and it flows both ways,’ Pinnington notes. ‘Our ability to serve the needs of both Canadian clients operating in or moving into or investing in the US, and US clients looking into Canada is a critical strategic differentiator.’ The McKenna deal brings former US ambassador to Canada, Gordon Giffin, into Dentons’ global partnership. ‘Giffin has developed a significant US-Canada cross-border practice,’ Pinnington notes.

The plunge in commodity prices and the consequent weakening of the Canadian dollar means the Canada-US trade connection (worth $707bn in goods and private services trade between the two countries in 2012) is even more important, Pinnington argues.

Investment also remains significant, with the US accounting for two-thirds of the C$67.3bn increase (to C$828.8bn) in the stock of direct investment abroad by Canada in 2014. Canadian banks are leading the way: the Bank of Montreal Royal, Bank of Canada and Toronto-Dominion Bank have been expanding internationally. The Trans-Pacific Partnership deal – signed in October between Canada, the US, Japan and nine other Pacific Rim nations and creating a huge liberalised economic bloc – makes the US connection even more valuable.

Divided opinion: debating alternative structures

The pros and cons of introducing alternative business structures in Canada has been the great debate of 2015 among the country’s 14 provincial and territorial law societies. In August last year, the Canadian Bar Association (CBA) released a report, Transforming the Delivery of Legal Services in Canada, which recommended that non-lawyer investment in legal practices be permitted, along the lines of the English model.

The report is the outcome of the Legal Futures initiative, a two-year research project into models of practice for lawyers that is similar in scope to the England and Wales Law Society 2020 strategy review. Fred Headon, chair of initiative, says: ‘The recommendation on ABSs [one of 22] is one that has generated a lot of discussion and reflection. A number of the individual law societies are now looking at the matter, and we have been in conversation with them.

‘It is a change that will take some time. We are talking more likely in months and years rather than weeks.’ There is resistance to ABSs, including from personal injury lawyers. Furthermore, while the CBA has made its recommendations, these must be considered in detail by each law society. Further, any change to their rules will very likely involve amending legislation across Canada’s 10 provinces and three territories, adding to uncertainty.

To investigate the issue, working groups have been established by law societies including the Law Society of Upper Canada which regulates Ontario’s lawyers and paralegals, and is the largest in the country. In a report issued in September, the Upper Canada working group was against majority-share non-lawyer ownership of traditional law firms ‘at this time’, although it was exploring and assessing ‘a subset of ABS models which might be applicable to Ontario’.

The CBA also recommended in its 2014 report that in addition to individual lawyers, Canada’s law societies should regulate law firms, and in due course ABSs, to ensure that ethical and professional standards are upheld.

Headon says the aim is to ‘strike a balance’. ‘On the one hand liberalising regulation by allowing for non-lawyer ownership, but then supplementing the current rules with entity-based regulation,’ he notes.

Manitoba has already amended its legislation to permit its law society to regulate law firms, Headon says, ‘and it is now up to the law society there to create the applicable rules’. Entity-based regulation has been getting ‘a lot of attention’ in other provinces such as Nova Scotia and British Columbia, he adds.

The Canadian legal profession has been following developments in England and Wales with a keen interest. ‘We were quite encouraged to see that the ethical sky did not fall in with the adoption of ABSs, that there are ways to maintain those ethical standards we agree are core to the solicitor-client relationship and must remain part of the foundation on which our professionalism is built,’ Headon says.

‘Once we secure the ethical foundation, opening the regulation to others may be a way to come up with some very exciting and new ways to deliver legal services,’ he adds, citing the example of BT Law, the ABS of British Telecom that provides business-to-business legal advice in the UK.

The CBA research found that cost and price predictability (clients not calling lawyers for fear of a spiralling bill) are preventing Canadians from seeking legal advice. Only one in seven legal problems in Canada is addressed with input from a lawyer.

‘Lawyers are losing their relevance in the life of the Canadians. How we make our services more accessible and relevant was really what drove this analysis,’ Headon says. ‘If we can learn from other businesses we can probably find a better way to deliver our services.’

While ‘the oil patch’ in the Alberta provinces of Calgary and Edmonton is suffering, a weaker Canadian dollar has historically given a boost to manufacturing based in the eastern provinces of Ontario and Quebec, Pinnington says. That is not just traditional output, but hi-tech industries that require legal advice such as design development and brand protection. With 500 lawyers across Canada’s six economic centres, including Montréal, Ottawa and Toronto in eastern Canada, Pinnington says Dentons is ‘extremely well-positioned’ to respond to such a shift in the economy.

‘Canada at the time [of the merger with Nicholl Paskell-Mede in March 2011] had done very well, it had not been as touched by the 2008 downturn, and insurers in particular were looking at Canada as a very stable and attractive market,’ McLauchlan says, arguing this is still the case. ‘[Clients] can’t get enough of Canada, although the economy is not as strong as it was several years ago.’

With offices in Toronto and Montreal, Clyde & Co focuses primarily on dispute resolution such as insurance and commercial litigation. McLauchlan says there has been an increase in litigation instructions over the past 12 to 18 months. ‘Business has been good. We are seeing an increasing number of disputes in the commodities and natural resources sector. Companies are even more attentive to litigation recoveries and are maximising their claims.’

DLA Piper is among the latest firms to enter Canada via a tie-up with mid-tier firm Davis, which brings 250 lawyers across seven Canadian offices, and expertise in sectors such as mining, infrastructure, transportation and related corporate and finance areas.

‘There are great opportunities in Canada, both from the perspective of Canada outbound and the rest of the world inbound,’ says Canada managing partner Rob Seidel QC. He does not expect a quick turnaround in oil and gas markets, but among the areas that will continue to perform well are transportation – a big industry in a big country – project finance and infrastructure, and related public-private-partnerships (PPP).

Davis is well-known in this field internationally, having advised on high-profile matters such as Bermuda’s first ever PPP project – the C$315m expansion of King Edward VII Memorial Hospital in Hamilton.

Infrastructure promises much in the coming years. In 2013 the previous government committed to C$80bn of infrastructure investment over the next decade, to build roads, bridges, subways, and commuter rail. The current pipeline of projects is significant, among them the Eglinton Crosstown light-rail transit in Toronto and the Site C clean energy project, a dam and hydroelectric generating station on the Peace River in northeast British Columbia.

The Seven Sisters

If some Canadian firms are joining forces with foreign counterparts, this does not yet include Canada’s magic circle, known as the ‘Seven Sisters’, or ‘Bay Street’ firms, a reference to Toronto’s financial district. Among them are Blake, Cassels & Graydon, Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg, Goodmans, and McCarthy Tétrault.

With 649 lawyers and consultants, including 286 partners, Blakes has 10 offices, among them Beijing, New York, London, and, through associations, in Manama, Bahrain, and Al Khobar, Saudi Arabia.

Asked whether the firm would consider an international merger, the unequivocal answer from London managing partner David Glennie and New York counterpart Geoff Belsher is ‘no’. Blakes does not want to compete with UK or US firms directly and has decided to grow ‘organically’ through lateral hires. Glennie says: ‘Our strategy is to be the pre-eminent Canadian business law firm, practising Canadian law.’ Belsher adds: ‘We feel that we have a winning strategy and that we are executing our strategy well.’

IN NUMBERS

35.54m

Population

$1.787tn

GDP

100,000+

Lawyers (plus 4,000 notaries in Quebec)

14

Number of law societies (mandatory membership) including two in Québec

37,000

CBA (voluntary membership) members

Sources: Federation of Law Societies of Canada; CBA; World Bank

There are no plans for additional offices outside of Canada, Glennie says: ‘We are very international – 50% or more of Blakes’ business has an international dimension. I don’t feel we are under threat by the Gowlings transaction. We have very strong relationships with the pre-eminent global firms, and if one or two of them no longer call us because they have entered into an arrangement with one of our competitors, that in some ways just takes one of our [rivals] off the playing field.’

Blakes covers a wide range of business-related practices, including M&As, corporate finance, financial services and banking, infrastructure, energy and mining, and international arbitration and litigation. The firm’s top-rated competition and antitrust practice represents ‘a huge part’ of Blakes’ advisory role in big merger deals that often require clearance from Canada’s Competition Bureau, Belsher says.

The fall in commodity prices has changed the nature of M&A activity, with a shift in dealmaking from listed companies to privately held organisations. In particular, there has been a ‘surge’ in private-equity-driven deals, he adds.

Other boom areas are financial services and regulatory, and ‘risk management’, buoyed by Canada’s foreign anti-bribery law, the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act. Canadian regulators ‘have become much more active’ in enforcing the act, in line with global trends, Glennie notes.

Blakes recently advised Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan on its direct investments in Italy’s Ducati Motor Holding S.p.A; KGS-Alpha Capital Markets (a US fixed income broker-dealer); and St James’s Gateway (an English mixed-use real estate development) as well as retail developments in the UK and Czech Republic. ‘Canadian pension funds are very significant investors globally now, particularly in property and infrastructure,’ Glennie notes.

Challenges

There are a number of challenges facing law firms – both domestic and international.

One is talent retention, resulting from more aggressive competition from in-house legal teams. Belsher says: ‘They are starting to pay competitively and they are attractive work places.’ A notable example of this problem is the closure of Allen & Overy’s representative office in Toronto in September (a year after launch) following the departure of François Duquette, the office’s sole partner and head, who went in-house at Canadian pension funds Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec.

Also, clients have become more cost-conscious because of the struggling economy and globalisation. ‘Certainly, there is concern over cost-control by all clients and that will be reflected in more narrow instructions or more careful [management] by in-house legal teams over, say, outsourced litigation,’ McLauchlan says.

‘Our mining, oil and gas clients are more sensitive to their budgets and they are trying to make sure they are getting maximum efficiency out of their law firms,’ Glennie says.

With more than 100,000 lawyers and a population of 35m, Canada is considered over-lawyered. ‘It is a jurisdiction which has more lawyers than it necessarily needs,’ Denyer says, pointing out that the country has traditionally exported lawyers to the UK and US, but this has diminished since the financial crisis. ‘Canadian law firms are seeking to respond to this by doing more work internationally.’

A further challenge, particularly when seeking to establish international tie-ups, is linked to the partnership structure of many Canadian firms, which have a lower leverage ratio of associates to partners than English counterparts. ‘This makes it more difficult to achieve a full-merger, one common global partnership,’ Denyer notes. ‘Typically, people become partners earlier in Canada, so joining an international firm where you have a fantastic experience and you get well paid but you don’t necessarily achieve partner status at the same point in your career… can be an issue.’

‘Canadian firms that enjoy or have higher leverage are most likely to combine internationally,’ says Seidel, formerly managing partner of Davis. ‘Our leverage has historically been higher than [that of] other firms.’

To get round this obstacle, firms can create ‘separate partnerships under one umbrella,’ Denyer explains, pointing to the swiss verein or similar models, where firms combine but remain financially independent. That is what Dentons, Gowling WLG, DLA Piper and others have done.

Finally, there are challengers to the traditional business model to contend with. ‘Technology has led to the emergence of alternative service providers, including accounting firms and start-ups, which are becoming meaningful competitors to the traditional legal profession,’ Pinnington says. ‘Certainly it’s true in the UK, and that’s starting to take hold in Canada as well’ (see box, p14).

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet