Solicitors should prepare for retirement as they prepared for their careers, hears Jonathan Rayner.

Goodbye tension, hello pension, as an anonymous rhymester quipped. They had a point.

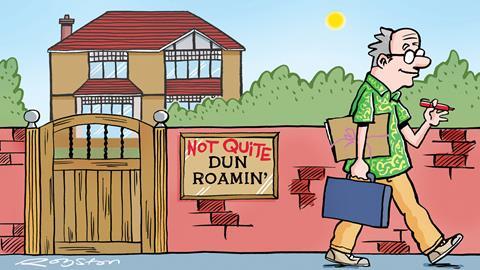

Retirement’s siren call is at its most seductive when, stressed and weary, you are crammed into a train, nose-to-nose with a stranger, and stopped at a red light. Or perhaps the siren is loudest on February mornings, leaving home in darkness, snowflakes swirling in the street lamps’ glow, fellow commuters grim and unsmiling.

Or it may be that retirement holds no appeal. It is having nothing urgent to do, but all day long in which to do it. You dread becoming the sad old person with the dog, haunting the neighbourhood to snare hapless passers-by with your gimlet eye and gibbering tongue. You want to work until you drop, you declare, because otherwise you are going to be bored witless. And you simply cannot agree with one of the retirees interviewed who states that just going for a walk ‘feels like skiving, which is lovely’.

And then there is the visceral aversion to retirement. You and your job are inseparable, you believe. Your profession defines you, gives you value, earns you respect. It keeps your mojo – your motivation and joy – working. Your profession is you and without it you are in death’s waiting room. A grim predicament.

And there you have the dilemma lawyers have about retirement. Other than the acknowledged problem some face in obtaining PII run-off cover, it is rarely about the mechanics of the process. We all know about pension plans and pots, annuities and drawdown funds, succession planning and run-off. The default retirement age is history. We are going to live longer and more active lives. But where do we want to be when we retire? What is the desired – or, at least, the most acceptable – outcome of those years of marking up leases, toiling in the courts or advising suspects at 3am in police station cells?

Paul Gulbenkian, former immigration judge and partner at London firm Gulbenkian Andonian, seemed to have it all. The day after he retired, aged 70, he moved to his house in Provence to spend the summer surrounded by vineyards, lavender and the mighty Rhône. It was to be a life of ease, a fitting reward after 50 years in practice.

Except just one month passed before he realised the idyll was not going to work. ‘I was missing being wanted by people in difficulty,’ he says. ‘I have hobbies, such as tennis and squash, but nothing – neither the beauty nor the weather of that glorious part of the world – compensated for my mind being unstretched.’

Gulbenkian consulted his family about a possible change to his retirement plans and, with their agreement, decided to ‘dip my toe in the water’. He tells the Gazette: ‘I was going to London anyway on charity business [he chairs several charitable trusts] and, while there, spoke to a former client who persuaded me to go back to representing him on a part-time basis and on my own terms.’

Word of his availability spread and ‘slowly, slowly,’ he says, ‘work began to filter through’ in the shape of consultancy offers from firms wishing to harness his half-century of experience. The Gazette suggests that really nothing has changed – he tried retirement for a month and then went back to work. Gulbenkian disagrees.

‘I’m working on a very selective basis,’ he insists, ‘keeping the old brain occupied. I might see clients initially, but then pass them on to be looked after by someone else within the firm. I’m simply a management and PR consultant nowadays. And anyway, I’m now able to spend longer in Provence than I could manage when I was in practice and sitting as a judge.’

A criminal law practitioner from north-east England, who asked not to be named, is less than bullish about his own retirement prospects. Despite working many years of long hours to build up his practice and achieve justice for clients, he is depressed most members of the public ‘have no clue’ that government proposals are likely to lead to the denial of access to justice for thousands of deserving people.

Have your cake and eat it

Denis Cameron, Law Society council member for central Lancashire and northern Greater Manchester, retired from private practice 10 years ago when he was 58. He now earns his living from lecturing on money laundering, regulation and conveyancing. ‘I’d been in practice 30-odd years and decided it was time to retire,’ he says. ‘Client attitudes had changed a lot over time. Apart from anything else, they had become more demanding and less inclined to pay.

‘What’s more, as you age, so do your staff; people who had been with the firm for many years were gradually retiring. I was faced with having to train younger people from scratch. Times were hard in the north-west and I would have had to restructure the firm. I was losing the energy to begin all over again. But at least, unlike many solicitors of my generation who were struggling to adapt to change, I could afford to retire from private practice.’

Cameron says that he was able to fund the gap between ending one career and starting another because, even while still in private practice, he had begun working as a lecturer. He has presented seminars on residential conveyancing since 1997 – eight years before his retirement. He writes articles on the same and related subjects. He also acts as an expert witness for the defence in money laundering and mortgage fraud cases involving conveyancing and conveyancing negligence cases.

‘Those wretched HiPs (home information packs) were also a useful buffer between practice and lecturing,’ he adds. ‘I found myself in great demand as an expert on HiPs [he was a member of the HiP taskforce of 2005-2007], with people attending lectures for CPD.’ Why ‘wretched’ HIPs?

‘After all our efforts, they were scrapped by the coalition government in May 2010,’ Cameron recalls.

Now 68 and newly married to Wendy Hewstone, managing partner of Southampton firm access law (they tied the knot on 21 June) Cameron intends to ‘carry on regardless’. In his case, it seems, a change is as good as a rest when it comes to retirement.

‘The government is planning to cut duty solicitor contracts from 1,600 to just 527 in England and Wales,’ he says. ‘It is also cutting our fees by a further 8.75%. It’s unsustainable. Many firms will have to close, including my own. I will have no choice but to retire.’

He concedes that he chose to work in one of the lower-paid areas of practice and never expected an affluent retirement. ‘If the worst comes to the worst, I will still want – and need – to carry on earning money doing something,’ he adds. ‘But it will have to be something that is not so stressful day in, day out.’

A former senior partner of a home counties firm, who also asked for anonymity, has a five-year plan for her retirement. Such a ‘long farewell’, she says, allows clients who have been with the firm for many years to get used to her impending departure. ‘When you’ve known the client 25 years, the worst thing would be to say that you’re leaving on Monday and good luck,’ she says. ‘They need to get used to your gradual withdrawing from the frontline.’

Her solution was, three years ago, to begin bringing in the next generation in the form of a 33-year-old successor to the senior partner role. He is presently a junior partner, she says, proceeding along the path she and the other senior partners have set for him.

‘Delegating is much harder than I would have guessed,’ she says. ‘It took me two years to pull back and achieve a 60% reduction in the amount of practice building and direct client contact that was the norm before. Parallel to this reduction, the amount of overseeing I now do has grown as clients continue to call me for reassurance and to OK deals. It’s time-consuming, but not disastrous. I’ve got it down to a fine art.’

Are clients happy? ‘Mostly,’ she replies. ‘One client was wounded and asked me whether I was fobbing him off. He felt unwanted, so I explained my five-year plan, which seemed to appease him. Others have noticed that I work from home more. They quickly got used to that, particularly when they realised that I responded faster because there are fewer distractions than in the office.’

She is hopeful that the transition to the next generation will work for the firm’s small and medium-sized enterprise and private clients. ‘I may have been dealing with dad,’ she says, ‘but his son might prefer my 30-something successor.’ She adds that she will probably take some clients with her into retirement, especially a family she has represented for 30-plus years.

She will also continue to ‘look after trusts’ and carry on with her various non-executive directorships. Other plans include becoming the chair of governors of her sons’ preparatory school; returning to the Prince’s Trust, where she used to work; and maybe doing a history degree.

‘In the meantime, I’m loving semi-retirement,’ she says. ‘It’s perfect. I’m not bored because I’m doing really interesting work for nice people, and I have lost much of the stress of building my own and the firm’s practice, not to mention looking after the firm’s finances. It’s the small things I love. I’m really enjoying just going for walks. It feels like skiving, which is lovely.’

The Gazette spoke to four solicitors – including Denis Cameron (see box above) – with four distinct attitudes towards retirement. All of them plan to continue working, two to earn a crust, two to keep a stake in the profession while also exercising their brains. None of them has an all-consuming passion, such as bee-keeping, brass-rubbing or bread-baking to occupy their waking moments.

But none of them plans to sit on the sofa watching daytime TV or otherwise luxuriate in a life of lethargy. The message is clear: plan for your retirement, the same way that you planned for your career. And remember, you probably chose the law because of its cerebral challenge; you will equally want to keep your brain active in retirement, too.

Jonathan Rayner is Gazette staff writer

No comments yet