There is little wrong with the 30-year-old Children Act, lawyers tell Marialuisa Taddia. But years of austerity too often compromise the legal process, challenging the ability of courts and social services to prioritise the interests of the vulnerable

THE LOW DOWN

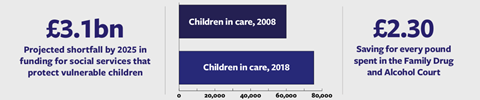

There has been an unprecedented increase in the number of care or supervision order applications by local authorities. Overstretched family courts have been under pressure to deal with them without delay, but the new 26-week time limit is routinely broken. Practitioners in child law are stuck between a rock and a hard place. Meanwhile, social services departments face a funding gap of £3.1bn by 2025. The enlightened approach of the Family Drug and Alcohol Court model offered hope to many children at risk and their families. But the FDAC too is under threat. Only an end to austerity can provide relief to courts, practitioners and clients.

Visitors to the Royal Courts of Justice must currently pass a protest, a desperate row of tents bearing slogans that accuse the state, the courts and councils of stealing their children. It is a striking tableau, underlying the pain that accompanies care and supervision proceedings, guardianship awards and adoption. Care and supervision proceedings that could lead to a child being removed from their family and possibly adopted are still within scope for legal aid – but as any lawyer doing publicly funded work can relate, the rates are low. What is more, the pool of firms doing legal aid work has shrunk after related areas, such as private family law, were taken out of scope.

And while advice on care and supervision proceedings is not means-tested, advice when adoption is in prospect is. The means test, which incorporates several criteria including any partner’s income, means the threshold at which parties become ineligible for assistance is very low.

As the Gazette went to press, however, there were encouraging signs that the government is preparing to release the straitjacket a little. It is bringing forward proposals to expand legal aid. As welcome as that would be, additional funds will be channelled into a system degraded by years of austerity.

Those providing paid-for legal advice and the voluntary advice sector are stretched. That is a particular problem when local authorities making care and supervision applications are themselves struggling with funding cuts. All this increases the likelihood of mistakes being made in what is a hugely emotive and important area.

The state is taking your child, and giving all the legal rights to an adoptive parent

Zoë Fleetwood, Dawson Cornwell

The Care Crisis Review, published last June, found that for the rising number of families who face care proceedings, ‘it is increasingly hard to access specialist, informed advice, because of significant cuts in the voluntary advice sector and legal aid reforms that have depleted the number of high street solicitors offering legal help and providing early stage advice’. Means testing in adoption cases is applied to all parties, including biological parents and special guardians. Many fail the test. As Zoë Fleetwood, a partner at Dawson Cornwell, observes: ‘The state is taking your child, and giving all the legal rights to an adoptive parent, and it cannot be right that the birth parent has to represent themselves in that situation.’

Fleetwood’s boutique family law firm is ‘turning away lots of people’ who are not eligible for legal aid and ‘doing a lot of work for free’, not just for clients, but also for judges. ‘Once they know that you are behind the scenes, and you have given advice [pro bono] to somebody, you can’t turn down a judge asking you to make some enquiries for free,’ she says. ‘We are committed to doing legal aid and have no qualms about not being paid very much, but not to be paid at all is very demoralising.’

Jerry Bull, director of Atkins Hope Solicitors and chair of the Law Society’s children law sub-committee, points to other ways in which overworked family judges in a stretched judicial system are adding to the pressure on lawyers. ‘There are far more proceedings and courts are expecting more of us each time, because they don’t have the resources to back up the judges, he says. ‘Whereas before the judges would do the orders, we are now expected to do all the orders for the court and email them in perfect form.’

Sir James Munby, who stepped down as president of the Family Division last July, described the ‘seemingly relentless rise in the number of new care cases’ as ‘a crisis for which we are ill-prepared’. But an increase in abuse or neglect of children ‘cannot be the sole explanation. It follows that changes in local authority behaviour must be playing a significant role’, he concluded.

Addressing the Association of Lawyers for Children in November, Munby’s successor, Sir Andrew McFarlane, said that families are not being appropriately diverted away from courts due to a failure in the Public Law Outline (PLO) pre-proceedings process. The PLO was first introduced in 2008 to manage care and supervision order proceedings under section 31 of the Children Act 1989. Set out in the Family Procedure Rules, this involves the local authority writing to parents to notify them that proceedings may be issued and inviting them to a meeting with social workers.

Pre-proceedings work is still in scope for legal aid. ‘If parents get proper legal advice, the hope is that then they can work with the local authorities and avoid the need for proceedings at all,’ Bull says. ‘There are times when the process works, but again it needs time and effort [and resources] from local authorities to be able to do that.’

Alistair Banks, a family law consultant at Edwards Duthie and a member of the Law Society’s children panel, notes: ‘If a local authority is prepared to carry out [expert] assessments, it can sometimes mean that the parents will accept things. Or it may prove that [the situation isn’t] quite as bad as the local authority thought in the first place. However, due to budgetary constraints, councils are reluctant to fund these pre-proceedings costs when they can share them with the other side in court.’

Then there is the timetable. As prime minister, David Cameron took a close interest in speeding up the progress of care proceedings, on the grounds that the more time a child spent in ‘limbo’ between permanent arrangements, the worse that was for the child’s interests. He also wanted to make adoption easier.

LIFELINE FOR ADDICTED PARENTS

There is universal praise for the Family Drug and Alcohol Court, whose ‘problem-solving’ approach was pioneered in 2008 in London by district judge Nicholas Crichton, who died in December. There are currently 10 specialist FDAC teams working in 15 courts covering 23 local authorities. FDAC tackles the problem of parental substance misuse underlying the need to remove a child.

IBB’s Vicky Preece describes FDAC as the ‘most progressive’ judicial initiative of recent years. ‘Research has shown that the long-term outcomes for families in which addiction is a feature are greatly improved if they are assisted through FDAC. In fact this can be a cost-effective approach in the context of the social work costs and legal costs generated by repeat court applications often associated with parents with addictions,’ Preece says.

Yet, FDACs are vulnerable to cuts in funding which comes primarily from local authority children’s services.

The FDAC National Unit was established in April 2015 to support the expansion of new FDACs across England and Wales with grants from the DfE and MoJ. However government funding stopped last September. The unit has since been running ‘at a minimum operational level while discussions continue about [it] in the longer term’ its website says. The FDAC sites continue to operate.

Hence, the Children and Families Act 2014 amended the Children Act 1989, with a revised PLO and a 26-week time limit to complete proceedings from the day they are issued. An extension may be granted, but only if it is necessary for the court ‘to resolve the proceedings justly’. The aim of the revised PLO was to reduce the average time of care proceedings from 42 weeks, explains IBB senior solicitor Vicky Preece.

Yet the shorter timetable has itself become problematic. In his ALC speech, McFarlane pointed out that ‘an undesirable consequence’ was the trend towards greater use of special guardianship orders (the formal court order which places a child or young person with someone permanently and gives this person parental responsibility for the child) in favour of family or close friends. He cited anecdotal evidence of ‘a relatively high incidence of breakdown in these arrangements, with the result the case comes back to court and starts again as a fresh application’.

Banks has seen this first-hand. ‘There have been cases in the last year or two where SGOs have been made and have broken down very quickly,’ he says. ‘Some break down for reasons that no one could have foreseen, but others [do so] for reasons which, had those special guardians been given proper advice, and perhaps taken part in the proceedings [as a joined party], and seen exactly what the whole family situation was like, what it means to be a special guardian, they might have had second thoughts.’

When it comes to care proceedings per se, the main issue – and there is little disagreement about this – is not one of procedure or substantive law, but of restricted resources.

The 2014 act restricted the use of experts in child care proceedings to circumstances when ‘necessary to resolve the case justly’. But Banks says that, based on his own experience in London, courts ‘much more easily allow for experts and that is simply because they don’t have the time to give each particular application the attention it deserves’. The national average case duration was 32 weeks in the second quarter of 2018-19, according to latest figures from Cafcass.

‘A change in the law isn’t going to do anything because the basics [are] perfectly appropriate and right,’ Banks says. ‘The only way forward is reducing the number of cases coming through the courts, [through] preventative work and fundamentally that is where the effort needs to happen.’

The Care Crisis Review, undertaken by the Family Rights Group with funding from the Nuffield Foundation, found ‘many overlapping factors contributing to the rise in care proceedings and number of children in care’ – though, many are linked to funding. It found that ‘lack of resources, poverty and deprivation are making it harder for families and the system to cope’.

Domestic adoptions

Most adopted children in England come through the care system, but while the number of children in care continues to rise, there has been a downward trend in adoptions. In the year to 31 March 2018, 3,820 children were adopted, a decrease of 13% on 2017 and down from a peak of 5,360 in 2015.

Of the children who ceased to be looked after, 13% were adopted (down from 17% in 2014); 11% were subject to a special guardianship order; and 31% returned to their parents.

‘Adoption remains the most contentious of the outcomes in care proceedings,’ according to a 2018 report by 4 Brick Court barrister Judith Pepper, published by thinktank Civitas. This is because it ‘severs’ the relationship between a child and their birth family, transferring all parental rights and responsibilities to the adoptive parents.

Yet, adoption is ‘an important form of permanency in the right case’, international and domestic adoption specialist Naomi Angell says. ‘There has to be a rigorous analysis before an adoption order is made, which will have to be the last option for a child, but still a very important one.’

Adoption numbers partly reflect changes in the law. Angell observes that the Adoption and Children Act 2002 (implemented in full in December 2005) marked a ‘shift’ in approach to adoption by making the ‘child’s welfare, throughout his life’ the ‘paramount consideration’ of the court or adoption agency – rather than just the ‘first consideration’. It also aligned the law on adoption with the Children Act 1989, through a ‘welfare checklist’ when considering the lifelong implications of the adoption order. One of the purposes of the act was to ‘promote greater use of adoption’. Adoptions nearly doubled between 1999 and 2005, to 3,770.

In 2013, the Re B and Re B-S judgments by the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, respectively, emphasised that adoption should be ‘the last resort’ after considering ‘all the options which are realistically possible’. The two cases, Angell explains, were tackling the ‘somewhat shoddy practice’ by local authorities and children’s guardians of making adoption decisions ‘without a rigorous and robust analysis’ of the feasible alternatives. But the rulings were ‘completely misunderstood’, at least initially, subsequently leading to a fall in adoption decisions and placement orders in favour of SGOs.

The coalition government’s Children and Families Act 2014 repealed the requirement (in the 2002 act) for adoption agencies in England to give ‘due consideration’ to ethnicity when placing a child. A child’s ethnicity is now one of the factors to consider but should not be a ‘deal breaker’.

Angell points to the ‘rigidity which had developed in adoption practice’ with agencies not placing children with adopters who did not reflect their religion, race, and cultural and linguistic background. She says: ‘It led to [prospective] adopters being rejected on the grounds that they weren’t an ethnic match,’ while children ‘were just lingering in the care system, which is a really bad thing for [them]. Fostering is often not stable, children move from one foster placement to another, they accumulate traumas and challenges in their behaviour and they become unadoptable.’

Where fostering for adoption does work it really benefits the child because, if they are in the care system, there is going to be the risk of a lot of moves to different foster parents

Naomi Angell

The removal of barriers to inter-racial adoption may in part explain the peak in 2015. For Angell there is no doubt that this development has had a positive impact ‘but possibly not as much as one would have hoped, because it comes down to the practice of adoption agencies, rather than the courts’.

The 2014 statute also introduced the concept of ‘fostering for adoption’, whereby a child is placed with foster carers who have also been assessed for adoption. The foster placement can then be converted into an adoption placement if the court agrees to it and the adoption agency is satisfied with the match. ‘Fostering for adoption has been pretty successful,’ Angell says, based on her own practice. ‘Where it does work it really benefits the child because, if they are in the care system, there is going to be the risk of a lot of moves to different foster parents.’

There has since been a reduction in the time a child waits to be placed with an adoptive family – from an average of two years and four months in 2014, to a year and 11 months in 2018, DfE data shows.

Placement orders allow local authorities to place a child with prospective adopters; after 10 weeks of residency they can apply for an adoption order. But Angell says that there has been ‘a real increase in the number of birth parents applying for leave to oppose an adoption application’.

One reason, she says, is the 26-week limit, which is a short time ‘for a lot of birth parents to be able to come to terms with the concerns about their parenting’.

Furthermore, ‘because the case law is there, it has been recognised as [a right of action] that is open to birth parents’, Angell explains. She refers to the Re B-S Court of Appeal judgment in 2013 where the mother of two young children sought permission to oppose the adoption order: ‘There has been a lot of litigation since, and it has developed the law [in this area].’

Most applications by birth parents are unsuccessful, as birth parents must demonstrate that there has been a significant change of circumstances and the child’s welfare requires the court to grant leave. But this can cause delays in the adoption process as well as uncertainty and anxiety for prospective adopters who are often ineligible for legal aid. Local authorities are the most likely source of alternative funding, but that is ‘patchy and usually inadequate’, Angell concludes.

That is but one more example of the ways that austerity and a diminished pool of expertise hamper the just operation of the laws on care, supervision and adoption.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet