The rule of law is central to the UK’s unwritten constitution, the source of much pride among the country’s lawyers, and is admired around the world. It underpins the foundations of access to justice, laid down in Magna Carta. These are truisms. As Lord Neuberger, recently retired Supreme Court president, put it: ‘Access to justice, and all the other rights we hold so dear, all flow from democracy and the rule of law.’

Yet, as Gazette readers will be all too aware, barriers are constantly being erected to prevent ordinary individuals from seeking legal remedies. ‘We have to face the fact that we are in something of a perfect storm. Legal services are increasingly very expensive and increasingly unaffordable to ordinary people. At the same time, government money to support the courts and legal aid is in very short supply,’ Lord Neuberger told the Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Justice last year. More recently, he compared UK governments to ‘repressive totalitarian regimes producing wonderful constitutions and then ignoring them’.

In fact, access to justice has become inversely proportional to the need for legal advice and representation. Aiming to reduce the £2bn annual legal aid bill by £350m-£450m a year, the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) tightened eligibility and removed from scope vast areas of civil law: private family law (except for domestic violence and child abuse), some debt and housing cases, most clinical negligence cases, employment law and welfare benefit issues.

At the same time, The Welfare Reform Act 2012 came into force with LASPO on 1 April 2013, capping household welfare, introducing the ‘bedroom tax’ and replacing council tax benefit with local ‘council tax reduction’ schemes. And there have been cuts to disability benefits since then.

The Grenfell Tower disaster highlighted the difficulties faced by working people in accessing justice. ‘There have been reports that tenants of Grenfell Tower were unable to access legal aid to challenge safety concerns, because of the cuts,’ pointed out Robert Bourns, past president of the Law Society. ‘If that is the case, then we may have a very stark example of what limiting legal aid can mean.’ LASPO has had ‘a corrosive impact on access to justice’ and ‘a wider and detrimental impact on the state and society’, Chancery Lane said in Access Denied? LASPO Four Years On, published in June.

In January, the government announced a much-anticipated review of LASPO. This was to begin with the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) submitting a post-legislative memorandum on the act to the Commons Justice Select Committee (JSC) by May, to be followed by a full post-implementation review.

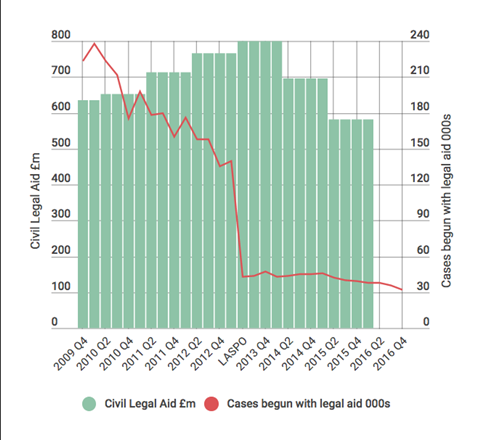

In their joint contribution to the JSC in August, a group of stakeholders – including LawWorks, the Law Centres Network, Legal Aid Practitioners Group, and the London Legal Support Trust (LLST) – provided evidence showing that civil legal aid helped just 253,000 civil cases last year (see graph). Furthermore, legal aid helped in none of the new disability benefit appeals (87,886 new Employment Support Allowance appeals and 104,236 Personal Independence Payment [PIP] appeals), even though most were meritorious.

Separate research by Amnesty International showed cases supported by legal aid almost halved in the year following the introduction of LASPO.

Access to justice has also been curtailed in other ways – for example, through hiking civil court fees by up to 600% in 2015, scores of court closures and restrictions to public funding for judicial reviews.

Criminal legal aid is also being reduced and the budget could be cut further to the tune of £30m annually. But Richard Miller, head of the justice team at the Law Society, says: ‘There is no evidence, yet, of people not actually being able to get the advice that they need [in criminal law]. It is on the civil side where we are seeing a combination of things: people are not entitled to legal aid anymore and that is causing serious problems, but more significantly now [they] are not able to access the advice they should be entitled to.’

Domino effect

LASPO also removed non-asylum immigration from scope, producing a domino effect, according to Sheona York, a solicitor at Kent Law Clinic, University of Kent.

First, it has led to a decline in the number of asylum solicitors, even though this area is still legally aided. ‘You are left with many firms who can’t survive as a business with just the asylum matter starts. There are places in the UK where there are no asylum lawyers near enough to people who need them,’ York says.

Second, ‘the effect for non-asylum immigration applicants is not just that there isn’t legal aid available, but there are fewer places to go, even if they were willing and able to pay, where there is any quality control or guarantee of experience,’ she adds.

In numbers

£350m-£450m - Government’s target for legal aid cuts on 2012/13 spending of £2bn.

253,000 - Number of cases civil legal aid funded last year. 13.5m people live in poverty.

£800,000 - Amount raised for legal advice centres and charities by the London Legal Walk.

80% - Proportion of family law cases removed from scope by LASPO.

Practitioners who advise under a legal aid contract are required to be accredited under the Law Society’s immigration and asylum law accreditation scheme. As legal aid funds have dwindled and many of those practitioners have disappeared, there has been an increase in new organisations that are regulated by the Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner (OISC), which is ‘a much lower level than the legal aid levels of regulation’, York says. There has also been a rise in new private solicitors firms that are not regulated under either system.

York says: ‘There has been an absolute drop in the numbers of experienced and highly qualified people available even to provide a paid-for service in immigration and asylum. The significant drop in the level and the intensity of regulation of individuals and firms who are providing immigration advice is leading to lower standards, which is now feeding through into poorer decisions in the tribunals.’ She cites Supreme Court judgments in Agyarko and Ikuga, in February, that addressed article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, and the July 2012 changes to family and private life immigration rules.

I wouldn’t have started those two cases,’ she says. ‘That is just the most vivid example of how you see lawyers taking cases with very, very weak facts.’

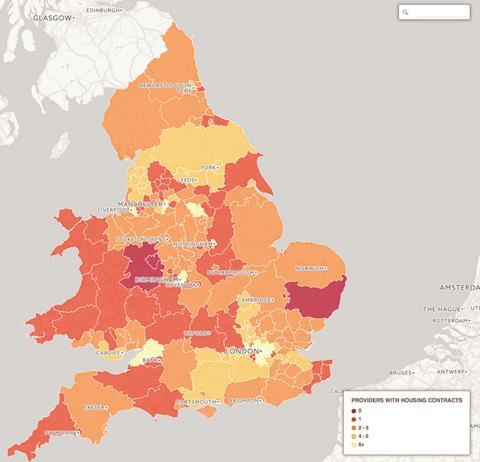

Not only has LASPO resulted in a drop in the number of asylum solicitors, it has also created ‘legal aid deserts’ for housing advice. ‘There are numerous areas in the country where there is only one housing provider left, and several where there is none at all,’ Miller says. Over the previous 15 months, the Society pointed out in a report, six areas saw their single provider disappear, resulting in the Legal Aid Agency having to take emergency action to ensure that services were restored. ‘The point that we have made repeatedly is they shouldn’t be waiting until they lose their last provider before taking action,’ Miller adds.

Then there is the impact of LASPO on eligibility: ‘First, none of the means test figures have been uprated since 2010 [for inflation and cost of living], so in real terms there has been a cut every year in the level at which you qualify for legal aid, and that is outrageous.’ Miller argues for a return to at least the 2010 level, which in his view ‘wasn’t exactly generous’. The income cap is currently £2,657 a month for a family with up to four dependent children. Second, LASPO introduced a new capital-means test that is tighter than the capital-eligibility rules for means-tested welfare benefits and includes equity in the home. With a home valued at £180,000 and a mortgage of £70,000, an individual would be ineligible. The Average UK home price is now £226,000.

Law centres have been at the sharp end of the cuts. Before LASPO, they were funded 45%-50% from legal aid, around 40% from local authorities and 15%-20% from charitable trusts and foundations, says Julie Bishop, director of the Law Centres Network. At the same time that legal aid was cut, so was local authority funding. By 2015 law centre funding had been cut by over 40% on average, says Bishop, describing this fall as ‘a huge hit’. Eleven law centres closed within the first year or so of LASPO: ‘Other [law centres] have managed quite successfully to get funding from trusts and foundations, [albeit] not entirely to make up the gap. Funds from trusts and charitable foundations have increased by over 50%.’

Yet, such alternative sources only provide a ‘limited solution’, Bishop says. ‘Law centres now take, on average, only one in three or four cases that they would once have taken.’ Moreover, they are relying on year-on-year support, or project-based funding, to deliver core work, which makes it difficult to plan long-term. And while the recipient of legal aid is generally protected from paying the other side’s costs, even if unsuccessful, that is not the case with other sources of funding. ‘A legal aid contract offers you protection from adverse costs orders, because the assumption is that the client can’t afford to pay,’ Bishop says.

Perversely, the upshot of all this is more litigation and more pressure on an overstretched court system. Vicky Ling, interim chief executive officer of London Legal Support Trust (LLST), an independent charity that raises funds for free legal services in London and the south-east, says: ‘LASPO reduced funding enormously, [but it also] focused it away from early intervention, so agencies were dealing with a lot of clients at an early stage of their problem, where [it] could be avoided.’

Fee and scope cuts have also led to a ‘dramatic increase’ in litigants in person, particularly in family law. This has, in turn, produced a fall in family mediations and ‘severe strain’ on courts.

The government hoped that greater use of mediation would offset cuts to early advice in family law. Instead, in the year after the reforms mediation assessments and mediation cases fell by 56% and 38% respectively. ‘Because people no longer have a lawyer telling them that mediation would be a good idea, and that they should go for it, they just go straight down to the courts and issue proceedings as litigants in person,’ Miller says.

’The removal of 80% of family law from scope has just meant that the courts are absolutely clogged up with litigants in person who are actually requiring the judges to act as solicitors and effectively case manage in a way that solicitors would normally have done,’ says Jenny Beck, family lawyer and chair of the Law Society’s Access to Justice Committee. ‘So cases are taking an awful lot longer, because obviously lay people don’t necessarily know [the law and how the system works].’

The justice select committee’s last inquiry into the civil legal aid reforms in 2015 found that LASPO had only achieved one of its four objectives: making significant savings in the cost of the legal aid scheme. But Beck says: ‘The only objective that was found to have been met had probably not [actually] been met because the savings that have been made directly to the legal aid fund have been spent elsewhere.’ In 2014, the increase in litigants in person in family courts cost the MoJ an estimated £3.4m.

Litigants in person are simply not detached or objective enough to conduct a case efficiently in court, argues Jo Shaw, barrister at 1 Essex Court. ‘Bringing a family case to court, even if you are represented, can be extremely stressful – let alone trying to deal with it on your own. It just doesn’t work in terms of people availing themselves of justice.

‘You end up with cases taking much longer in terms of court time and it is all very expensive and frustrating for the judiciary,’ Shaw adds. ‘The stats on the morale of the judiciary are really quite shocking because judges are thinking: “Why am I bothering to do this job, if I am not being taken care of in terms of how the system operates?”’

In 2016, the proportion of judges that said they would leave if it was a viable option (42%) had almost doubled on 2014 (23%) (Judicial Attitudes Survey).

Unresolved civil legal problems have a knock-on impact on physical and mental health, and offending behaviour.

Legal aid funding has also been removed from all private law family cases such as divorce, finances and child contact. Beck cites the example of when contact arrangements are not resolved: ‘People can’t see their children anymore and they take the law into their own hands. They can’t go to a solicitor to get [initial] legal advice on how to pursue an action to get contact so they decide to go round and get their kids, and police get called.

She adds: ‘There is going to be a lot more fragmented family life. We are going to see a whole generation of children growing up with only one parent. I know that sounds overdramatic, but I have seen evidence of it.’

Matthew Hardcastle is an associate in the criminal litigation department of Kingsley Napley, who switched from a legal aid practice a year ago. ‘If there is a reduction of support in one area that could have a knock-on effect into other areas. We have certainly seen that [when] representing defendants accused of criminal offences,’ he says. ‘We’d very often see clients who had multiple issues when they came in but were only able to receive advice for the issue of the day [for example, they were under arrest]. When speaking to them you’d find out actually there was a myriad of other problems that inevitably had led, or at least contributed, to where they found themselves.’ Those problems included family, debt and housing issues.

Palliatives?

Martin Barnes, chief executive of LawWorks, says that while access to justice has been undermined in various ways, ‘LASPO is the biggest factor. There is no question that it has left greater areas of unmet need and then in turn a pressure for pro bono to try and address that’. But he stresses that pro bono ‘isn’t and should not be seen as an alternative to legal aid’.

‘Overall, pro-bono can only make a contribution. It can’t fill, or be expected to fill, what has become a very big, widening gap in provision,’ Barnes stresses.

The traditional pro bono model of the past was largely limited to early initial legal advice, explains Barnes. ‘We are now seeing more firms offering what we would call “in-depth pro bono” – specialised case work, for example, representing at the social security and child support tribunals.’

The London Legal Support Trust raises funds for law centres, advice agencies and CABs through events such as the London Legal Walk. ‘Last year, we were able to give £840,000 worth of grants to not-for-profit agencies in London and the south-east. This year, the walk raised £800,000 on its own and we do have a range of other events coming up [for example, the Royal Parks Half Marathon],’ Ling says. Similar walks take place in the regions.

The not-for-profit legal sector has ‘had to be very pragmatic’ in the face of adversity. ‘We know that the kinds of problems that agencies’ clients have are often related to health issues,’ Ling says. So, for example, free legal advice agencies in some areas have formed partnerships with clinical commissioning groups (responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services in their local area) to access funding, and work with local GPs.

Some law centres have partnered with intellectual disability charities, and raised funds for ‘crisis workers’ to accompany the lawyer and client to court on eviction or possession day. And once court proceedings have ended, they help solve related issues, for example debt, through referrals to a financial adviser, Bishop says.

But these and other initiatives are ‘a drop in the ocean’ compared to what has been lost, says Ling. ‘If you look at it overall, funding for the sector is down, despite how creative local agencies are being.’

What about technology? The government argues technology can facilitate access to justice and HMCTS is in the midst of a £1bn modernisation process involving virtual hearings (for example). For Roger Smith, visiting professor of law at London South Bank University and for many years a Gazette columnist, new technology will have an ‘enormous’ impact on the legal profession and the provision of legal services, led by deep-pocketed big commercial firms.

‘Down at the access to justice end, you can see how technology could help reduce the cost of legal services for those on low income, but they face different barriers: one is the cost of implementation. Firms in what was the legal aid area don’t have the money to do that,’ Smith says. ‘They also face a clientele who will be much more unfamiliar with the use of digital communication. I don’t think you can assume digital literacy much above 50% in the population group eligible for legal aid.’

Smith points to technology innovation elsewhere: MyLawBC in British Columbia and Dutch Rechtwijzer. Developed by the Dutch Legal Aid Board, the Hague Institute for the Internationalisation of Law and US firm Modria as an online-based dispute resolution platform, initially for people with divorce-related issues, Rechtwijzer was terminated in March. ‘They tried to move too quickly to making it financially self-sustaining. People had to pay to use parts of it and they weren’t quite at that point,’ Smith says. ‘But the lesson is that there is still a wide-open area for digital services, which will help people at very low unit cost in the areas of law that affect people on low income.’

Barnes, for his part, points to research by the National Literacy Trust which shows that one in six people in the UK struggle with literacy: ‘The key thing is to recognise that for all the advantages that court modernisation and technology might provide, while the law remains as complex as it is there is never going to be true equality of arms. That is why it is important that those who are more vulnerable do have access to legal advice and indeed representation.’

The Society’s LASPO report listed 25 recommendations, including: reinstating legal aid for early advice in family law (at an estimated cost of £14m), housing (housing benefit, rent arrears and mortgage problems), and for parties involved in Special Guardianship Order applications; removing the mandatory requirement to use the telephone gateway for debt, special educational needs and discrimination law, and ‘immediately’ bringing back available access to face-to-face advice in these areas; scrapping the capital means tests for people on means-tested welfare benefits; and routine uprating of civil legal aid means tests for inflation and cost of living.

‘We recognise that the government is going to be very difficult to persuade to make changes at the moment, and so it was a question of focusing on where we’re seeing the most acute need arising,’ Miller says, responding to criticism that the Society failed to address non-asylum immigration in its report.

Ling says: ‘If you think about the legal aid system that we had before LASPO, it wasn’t perfect, it could have done with some changes. But I would certainly very much hope that some of the worst impacts of LASPO could be changed, for example [the lack of] legal aid for non-asylum immigration matters. That is an urgent matter to be reviewed. The feedback we got from our frontline agency partners was that, as soon as the Brexit vote came through last year, they were inundated with queries from people who were extremely worried about their family and their own situation.’ Currently, the ONS estimates some 3.6m EU nationals live in the UK.

Expectations about LASPO reform do not seem high. ‘I can see no political scenario in which the government prioritises the reinstatement of the LASPO cuts. Once you have made cuts of that magnitude, they ain’t coming back,’ says Smith. ‘What I think is a more realistic objective is that there is a bit more money released into legal aid, but it is for new forms of delivery, which are digitally assisted.’ While accepting short-term budgetary pressures, Barnes is more hopeful that the case can be made for the cost-effectiveness of legal aid, arguing that it is important for lawyers to ‘engage robustly with the review process’.

Bishop says there ‘are a lot of senseless parts in the reform, but if [the government is] to do one thing, and one thing only, they have to bring back into scope related matters,’ such as employment, immigration status, welfare benefits and ‘basic’ family law: ‘These are invariably the sort of issues that are leading to the person being evicted.’ Shaw would like to see ‘all the family law cases’ – from early advice through to representation in court – back in scope.

In a decision widely hailed as victory for access to justice, the Supreme Court ruled in July that the government acted unlawfully and unconstitutionally when, in 2013, it introduced fees for those bringing employment tribunal claims. ‘That was a really powerful judgment. The Supreme Court did a really good job at setting access to justice at the heart of British common law, and saying this isn’t just some sort of airy-fairy concept but it is a right, at the heart of British common law, which is enforceable in our courts,’ Miller says.

‘We are looking at whether the arguments that the Supreme Court spelt out in that judgment do actually have wider implications for other [access to justice issues],’ Miller adds, pointing to the increases in civil court fees in 2015, the MoJ’s proposals to raise the small claims limit for personal injury cases, and plans by the MoD to prevent military claims going to court, for example in cases where soldiers were killed or injured as a result of inadequate equipment.

In its landmark judgment, the Supreme Court cited the Magna Carta: ‘We will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right’. Words many lawyers surely feel have been often unobserved in recent years.

The days when legal aid was created to sit beside the newly-minted NHS as a key element of the post-war settlement seem ancient history to those providing and promoting access to justice. They received a fillip recently with the publication of the Bach Commission report.

Labour peer Lord Bach worked under the auspices of thinktank the Fabian Society, and delivered final recommendations in September. Pointing out that legal aid spend last year was £950m less than in 2010, £400m lower than expected when LASPO was introduced, the commission urged reforms that would provide access to justice, while falling within the original proposed cut.

The commission recommended a ‘Right to Justice Act’ which would create the right to ‘reasonable legal assistance, without costs individuals cannot afford’. Enforceable through the courts, the right would have a set of guiding principles, including ‘the importance of early legal help, public legal education, and the smooth operation of the system’.

It proposed that in bringing more people and areas back within the scope of legal aid, receipt of a means-tested benefit would qualify someone for legal aid. It also argued that an owner-occupied house should not count in assessing whether someone qualified for legal aid.

Notably, the commission wanted a ringfenced fund for advice providers. Another proposal was the creation of an online portal for advice and information on legal rights.

When Bach started work on the commission, such aspirations would have seemed positively utopian. Implementation is still unlikely – but when graphically linked to an event like Grenfell, which demands a response, access to justice is more difficult to ignore. At the very least, Bach’s ideas no longer seem politically impossible.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist.

1 Reader's comment