Digitisation and a focus on more subjective business goals have made the act of measuring value a moveable feast. Yet there is no doubt that technology can enhance this process

How do you know if tech – or anything else – adds value? Measuring is a good start, but it may not be enough. ‘What gets measured gets managed – even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organisation to do so.’ The first half of this quote is commonly attributed to management theorist Peter Drucker, but as Danny Buerkli of the Centre for Public Impact revealed in 2019, it was actually from columnist Simon Caulkin’s summary of V.F. Ridgeway’s 1956 paper, Dysfunctional Consequences of Performance Measurements.

At last month’s Legal Innovators conference, Jeremy Coleman, head of innovation at Norton Rose Fulbright, preceded his keynote speech with an impromptu move. He borrowed a tape measure and measured the stage. He did this to demonstrate that if you’re going to measure something in a meaningful way, you need a generally understood standard of measurement: otherwise, you can’t easily make comparisons or establish value.

[Crypto-art tokens are] a new way of selling our legal services, an innovative use of a new and evolving technology that shows our clients that we are investing in the space, not just advising on it

Will Foulkes, Stephenson Law

Time is still the common unit of measurement for law firms. This is a significant factor in the survival of the billable hour (notwithstanding the enduring movement to replace it) and the drive towards price transparency across the sector. It is also key to understanding the impact of investing in technology and innovation – and sustainability measures. For example, the number of users and time they spend using a software application will indicate whether it is (still) adding value, or whether it has become (virtual) shelfware. And as applications are increasingly online, it becomes easier to adjust your tech portfolio and cancel or replace underutilised resources.

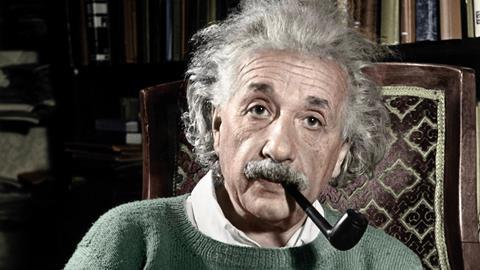

But as Albert Einstein allegedly said (in a quote that has been attributed to him): ‘Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted.’ In these digital times, value has become a moveable feast, particularly given the current focus on ESG (environmental, social and governance), including ethical standards, sustainability and wellbeing, which are more subjective. This article considers three value-adds which are enhanced by technology.

Return on investment and innovation

ROI is financial terminology for return on investment. How do you make sure you are getting a return on your tech investments? Well, it depends on what you are looking for. It is straightforward to measure the ROI of systems and software that save time, money and headcount while improving accuracy and agility. Business continuity is another value-add for firms that moved their systems to the cloud to facilitate remote and mobile working.

Technology may also add value beyond productivity/efficiency through improved job satisfaction and retention. And the past 18 months have demonstrated the value of technology in connecting lawyers and staff with each other and their clients, and managing risk. Teams, Zoom, Citrix and so on have kept people engaged, and digital events platforms such as Hopin (the fastest-growing European start-up of all time by valuation) have kept them in touch with their peers as well as thought leadership and industry development.

When considering ROI on innovation (ROII), it is also worth considering developments that make a difference despite this not being immediately reflected in financial statements, number of hours, recruitment or business development. Topical examples include identity verification, tokenisation and, in light of Cop26, how technology is helping firms deliver on green policies and protocols.

Cybersecurity and compliance tech and training help protect firm data, client data, and everyone’s reputation. Rather than boosting productivity or cost reduction, the value is in what doesn’t happen, which is difficult to measure precisely as you may not identify every potential threat.

Identity crisis

One downside of shifting services online has been an increase in fraud. Recent media stories show that fraudsters are getting past the plethora of regulation, technology, cyber training, penetration testing and other safeguards, in ways that could potentially undermine the digitisation of legal services.

The BBC reported on 1 November that a man in Luton discovered his house had been sold without his knowledge by someone who had impersonated him to get past the checks required to prevent exactly this type of fraud. While the Law Society has launched an awareness campaign about push payment fraud – the ‘Friday afternoon emails’ sent by fraudsters pretending to be the victim’s lawyer and asking them to divert payments to a different account – this incident highlighted the vulnerability of banks and institutions (in this case, the DVLA had issued the fraudster with a duplicate driving licence in the victim’s name and the banks had accepted this). And last year the Land Registry paid out £3.5m in fraud compensation. This type of story – together with the 2018 Dreamvar decision, which ruled that solicitors representing parties in fraudulent property deals should share responsibility for victims’ losses – means that many firms will only accept physical (paper) documents as proof of identity and ownership. But is the human eye better than technology at recognising whether a document is fake?

Olly Thornton-Berry, co-founder of Thirdfort, a conveyancing start-up designed to combat property fraud, explains how the Thirdfort app uses advanced technology to combat identity fraud, money laundering and push payment fraud. For example, it is integrated with Onfido to verify identity documents. This includes AI document scanning – including the ability to read passport MRZ (machine readable zone) numbers – and biometric authentication of photo IDs whereby a live video is used to match someone’s face with the photo on their document. Thirdfort uses ReadID NFC (near-field communication) chip-scanning technology to check passports. When a lawyer logs into the Thirdfort platform they can choose how to verify a client’s ID documents. The client then downloads the app and uses their smartphone to verify their documents and upload bank statements directly from their bank. This takes the burden off the lawyer, who may be unable to differentiate between real and fake documents.

A greener future

The following initiatives provide online resources to help firms and clients reduce their environmental impact:

- Relaunched in 2020, the Legal Sustainability Alliance has developed a library of online tools for measuring and managing carbon footprint and engaging employees in sustainability programmes. The ‘No-Fly’ Carbon Calculator requires a licence, but other tools and guides are free to download.

- The Campaign for Greener Arbitrations includes technology in its guidance and protocols. Founded in 2019 by international arbitrator Lucy Greenwood, it brings together practitioners, institutions and legal service providers with guiding principles such as using technology to facilitate sustainable behaviours. These include creating a workplace with a reduced environmental impact, corresponding electronically, using videoconferencing as an alternative to travel for hearings and collecting witness statements, and avoiding hard copy/printing where possible.

- The Chancery Lane Project has developed climate-conscious model clauses that can be incorporated into commercial, supplier and insurance contracts, helping law firms and their clients switch to greener practices, suppliers and investments.

A new way of valuing legal advice

Last week saw the UK’s first legal NFTs (non-fungible tokens) sold by Bristol firm Stephenson Law on OpenSea (which uses less energy than other NFT platforms). The common metric is still time, but it is being traded in a new way. An NFT is a unique unit of data on the blockchain (such as an original piece of art, rather than a digital currency such as bitcoin). Its value is derived from ownership, so although the token can be replicated, the owner gets a percentage every time it is traded.

Stephenson Law’s crypto-art tokens entitle owners to one-on-one access to the lawyers behind the project. It costs £300 for a token worth one hour with Will Foulkes, head of blockchain, or Gareth Malna, head of FinReg, and £250 for 30 minutes with Stephenson Law CEO and founder Alice Stephenson.

As Foulkes explains, Stephenson Law’s NFTs are about valuing legal advice as a utility. They also flag up the firm’s expertise in and commitment to blockchain and decentralised data. ‘Although the art is quite cool, you get to redeem the token,’ he explains. ‘It’s a new way of selling our legal services, an innovative use of a new and evolving technology that shows our clients that we are investing in the space, not just advising on it.’

Legal tech and green credentials

The legal sector had its sights set on a greener future well before Cop26. Technology can monitor and encourage greener behaviours, facilitate practices that reduce the sector’s carbon footprint and conduct impact assessments.

While hybrid working will no doubt lead firms to re-evaluate the size and location of offices and maintain flexible working practices, security concerns have slowed progress towards paper-free or at least paper-light working.

Client-facing technology can help businesses become more environmentally conscious. For example, applying smart contracts to climate clauses – to define standards, flag up breaches and automatically apply penalties when they are not met – was highlighted at Legal Innovators. But although this is a strong move from talking to action, automatically applied penalties seem less engaging than Tim Peake’s suggestion at Cop26 ‘to make the green choice the easy choice’.

While it is important to recognise that technology itself is not carbon neutral, a green tech strategy – which should also include suppliers – will reduce a firm’s carbon footprint and boost its environmental credentials.

No comments yet