Four leading US law firms chose to fight president Trump’s executive orders through the courts. The first full judgment has come down in the sector’s favour – is the tide turning on the White House?

‘If Skadden weren’t there, who would miss it?’ This brutal question caught the attention of partners of US-headquartered firms who downloaded a podcast on the president’s decision to target law firms for past cases they had brought for clients, and the lawyers they had hired. Firms’ diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies were also in Trump’s sights.

Skadden pre-empted receipt of an order by dealing with the White House before one was issued.

The answer to the question is not clear cut. Maybe that is why it is being used to shape the thinking of other firms as they decide how to respond to Trump’s attacks.

Orders

The White House has acted against law firms in two ways. The first, and most noticeable, has been executive orders. The second has been letters to a wider group of 20 firms from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). These demanded information about those firms’ DEI policies, based on the position that any sort of treatment of underrepresented groups that appeared preferential to that group in policy or practice was unequal treatment for other groups, and therefore discriminatory. That point was also commonly present in the executive orders.

The first order was against Covington, on 25 February, but while unprecedented, it was also narrow in scope. The order suspended the security clearance of lawyers who had worked with special counsel Jack Smith, who was appointed by the justice department and who had brought criminal charges against Trump after his first term. It also initiated a review and termination of the firm’s federal instructions.

The Covington order proved to be a straw in the wind, indicating that the president intended to make good on threats against lawyers and jurists made while he was out of office. It was clearly a vendetta.

Existential threats

A 6 March order, ‘Addressing risks from Perkins Coie’ went much further and established the format for others that followed. In its ‘purpose’, the order equated past cases which were disobliging to the president’s interests and views (‘dishonest and dangerous activity’) with the national (and national security) interest. This was the justification for what followed, including the withdrawal of security clearances for all the firm’s personnel. This effected a bar on them entering federal government buildings, including the premises of regulators and courts. It required private businesses with government contracts to report on and terminate instructions to the law firm or lose their contracts.

The order labelled the firm’s DEI policies illegal, and barred federal agencies and businesses with government contracts from hiring personnel from the firm.

Perkins Coie’s transgression, according to the order, was that ‘in 2016 while representing failed presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, [the firm] hired Fusion GPS, which then manufactured a false “dossier” designed to steal an election’. (Top Democrat lawyer Marc Elias had been a Perkins Coie partner, but left to start his own firm in 2021.)

This was an unprecedented interference in a private business by federal government, let alone a law firm, in the face of numerous constitutional protections against such retaliatory actions.

The format was followed in an order against Paul Weiss on 14 March. Paul Weiss had brought actions against protesters at the US Capitol Building on 6 January 2021 and investigated Trump during his first presidential term.

Another followed against Jenner & Block on 25 March. The firm’s offence was to hire Andrew Weissmann. No longer with the firm, Weissmann had worked with Robert Mueller, special counsel in the Trump-Russia investigation.

WilmerHale, likewise a firm with a past connection to Mueller, was the subject of another order on 27 March on the same ground.

Susman Godfrey followed on 9 April. The firm had successfully represented Dominion Voting Systems in election-related litigation, when false accusations were made about its voting machines during and after the 2020 presidential election.

Taking a stand

Perkins Coie immediately decided to challenge the legality of its executive order (successfully, see box, p10). Paul Weiss had negotiated that its order be rescinded, in return for $40m of pro bono work for White House causes, and agreeing to ‘not adopt, use, or pursue any DEI policies’. Critics say that this agreement represents permanent government interference in the work it can undertake.

In weighing its own response, Jenner & Block partners had before them the example of Paul Weiss’s capitulation, and the knowledge that Perkins Coie had achieved a temporary restraining order preventing implementation.

Sources close to Jenner & Block told the Gazette the partners looked at the Paul Weiss deal’s apparent terms, and came to a very different conclusion – one which the firm united behind.

A particular red line was the restrictions on future work. For a firm that did a deal, there would be two masters. For every matter, the firm would have to consider if work for the client conflicted with the US government’s ‘interests’, to use the language of the executive order. The term being used within firms is the ‘government interest layer’.

There was a firm conviction that something had to be said about an order that so disadvantaged clients. Clients with federal government contracts faced the incredibly difficult task of being ordered to move their matters to another firm, or face termination of their government contracts. The client, it was noted, could be midway through a trial. Being a client’s lawyer, it was stressed in internal deliberations, was not merely transactional, but hedged by multiple ethical, professional and regulatory duties.

Clients also faced, by extension, significant barriers to taking a contrary position to the government, now conflated with both the national and national security interests. In bringing a case challenging the executive order, sources close to Jenner & Block say the firm regarded itself as defending principles that are ‘table-stakes’ for the profession. The order was regarded as anathema to the US constitutional system. That Trump’s orders targeted work including pro bono was seen as particularly harsh.

Jenner & Block, like Perkins Coie, obtained a temporary restraining order (TRO) relating to its executive order. WilmerHale and Susman Godfrey were also successful in part in obtaining the TROs they sought.

So what now?

'Clients may harbor reservations about the implications of such deals for the vigorous and zealous representation to which they are entitled from ethically responsible counsel'

Federal judge Beryl A. Howell of the District of Columbia

Perkins Coie now has full judgment in its case. Federal judge Beryl A. Howell of the District of Columbia ruled the order null and void. And there is growing confidence that the courts will find similarly for other firms that have brought cases against the Department of Justice. Jenner & Block’s judgment is expected soon.

Howell’s judgment is complex but clear. The degree to which clients’ cases and their legal representation is bound up in the US constitution and the case law of courts at all levels, including the US Supreme Court, is set out as so unambiguous, authoritative and extensive as to be repetitious. It is clear in Howell’s judgment that on many points, the government’s case fails with reference to its own arguments, to the president’s own statements, and with reference to the content of the executive orders themselves. The orders are ‘retaliatory’, evidenced by the fact that firms have been the subject of an order for the actions of lawyers who are no longer at the firms in question.

The position of firms that were targeted and which opted not to fight is precarious. Judge Howell said of firms that reached a deal: ‘Clients may harbor reservations about the implications of such deals for the vigorous and zealous representation to which they are entitled from ethically responsible counsel.’

That number includes firms written to by the EEOC that reached deals with the White House, the terms of which, Howell consistently notes, are ‘fuzzy’. Government lawyers were unable to produce details.

Are some now feeling queasy about their capitulation? Perhaps. On 6 May, reported Reuters, five had written to Democratic party legislators, ‘saying they did not compromise their principles in pledging free legal work to causes the White House supports’.

Four of those firms – A&O Shearman, Cadwalader, Latham & Watkins and Simpson Thacher – specifically assert that they retain the independence to pick their clients and cases following their deals with Trump.

Hundreds of law firms, lawyers and legal groups signed up to amicus briefs in support of firms that have brought cases against their executive orders. The White House has now broadened its assault to include the American Bar Association, directing the withdrawal of funds for various projects, after the ABA voiced its opposition to the executive orders. The ABA is fundraising for its campaign to support its stance, and has obtained a temporary order blocking a Department of Justice decision to cancel $3.2m in grants for the ABA to train lawyers to represent victims of domestic and sexual violence.

What happens next, assuming all the executive orders challenged are nullified in federal court cases, is anyone’s guess. But a few months ago, it would have been inconceivable that ‘Big Law’ would break from concerns about PEP and big-ticket M&A to require such a ‘Spartacus’ moment.

Executive orders: settling scores

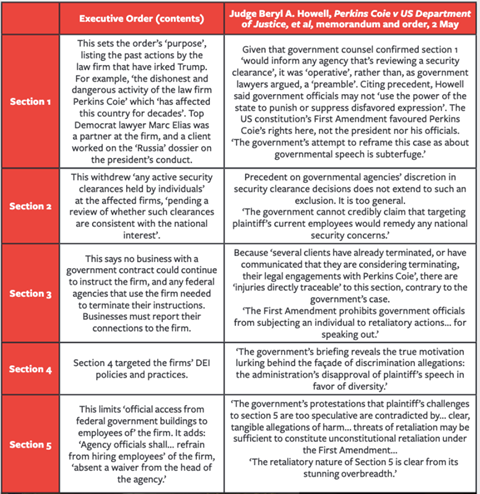

Executive orders against Perkins Coie, Paul Weiss, Jenner & Block, WilmerHale and Susman Godfrey followed the same format and had similar content, set out in sections. Paul Weiss has reached a deal with the White House. The others filed lawsuits, and final judgment has so far been given by a federal judge in favour of Perkins Coie, indicating the determination that might be reached in other cases.

This article is now closed for comment.

9 Readers' comments