Libel, privacy, criminal and employment law issues jostled for prominence in the scandal that arose over the alleged behaviour of a BBC presenter. Lawyers assess the likely fallout from a crisis that spiralled out of control

The Sun newspaper’s 8 July headline ‘top BBC star in sex pics probe’, and much that has followed since, set legal minds racing.

First there was the issue of identification. With no name provided, identification was a problem. Any male BBC presenter on a ‘six-figure salary’ found they were in the frame. ‘There is a potential libel claim for the innocent individuals identified,’ Mark Stephens, partner at Howard Kennedy, says. ‘The six-figure salary identification took some suspects out of the frame, and put others in it.’

So why did the Sun not name the presenter?

‘One possible explanation is that the Sun wanted to create intrigue and prolong the life of the story, which would also have the effect of placing the BBC under scrutiny,’ says Iain Wilson, partner at Brett Wilson.

But as this came with an enhanced libel risk, is there a further legal explanation? Two cases established a right to privacy for suspects under police investigation. Elizabeth Wiggin, senior associate at specialist media firm Wiggin tells the Gazette: ‘The decisions in the cases of Bloomberg v ZXC and Cliff Richard v BBC have fuelled confusion around what can and cannot be reported on in this connection and have arguably had a chilling effect on free speech.’

The next day came a heavy hint at criminality in The Sunday Times and the Sun, based on comments by former chief crown prosecutor Nazir Afzal, who told The Sunday Times that the presenter could potentially be charged with sexual exploitation under the Sexual Offences Act 2003. ‘Top BBC star who “paid child for sex pictures” could be charged by cops and face years in prison,’ ran the Sun’s headline.

But it has become clear that police interest in the case did not precede its media coverage. And by 13 July, the police said the presenter had no criminal case to answer.

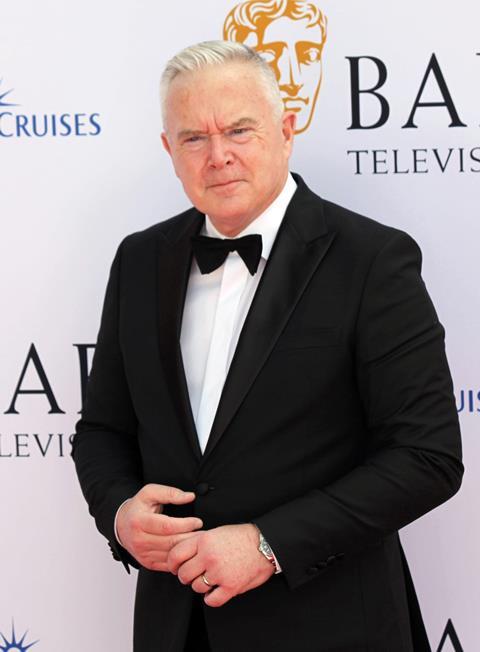

In that context ‘the Sun’s decision not to name [Huw Edwards] is a curious one’, says Wilson. ‘The Sun’s admission that it did not intend to allege criminality in the original article is strikingly at odds with the imputation readers are likely to have drawn from the original allegation that the young person at the heart of the story was given “more than £35,000 since they were 17 in return for sordid images”. In libel… the relevant test is what the reasonable reader would have understood the words to mean.’

The story was changing, and as Stephens puts it: ‘It’s important to document how the Sun’s story changed.’

'The decisions in the cases of Bloomberg v ZXC and Cliff Richard v BBC have fuelled confusion around what can and cannot be reported… and have arguably had a chilling effect on free speech'

Elizabeth Wiggin, Wiggin LLP

Counter-claims

On 11 July, a lawyer for the ‘young person’, who is now 20, wrote to the BBC calling the claims ‘rubbish’, adding that their client had contacted the Sun the day before publication saying their mother’s account given to the paper was ‘totally wrong and there was no truth to it’. ‘For the avoidance of doubt, nothing inappropriate or unlawful has taken place between our client and the BBC personality,’ the lawyer said.

Another day later, Huw Edwards’ wife, Vicky Flind, issued a statement revealing that the news anchor was the BBC presenter in question, and that he was in hospital receiving treatment for mental health problems. The statement was perhaps in her and her family’s interest, but it might weaken a future claim as she, and not the Sun, revealed the presenter’s identity.

At the time of writing, all of the Sun’s original stories remain online and unamended, but certain references have changed in new articles. An online Sun editorial on 12 July did not mention the age at which ‘the young person’ allegedly started receiving payments. And it said the newspaper had not alleged criminality.

What else had happened? The BBC had identified a second person who made accusations against the presenter, while it emerged Newsnight presenter Victoria Derbyshire had been following up a story of alleged ‘unwanted’ behaviour by Edwards towards a staff member.

Edwards has not responded to any of the allegations made. Flind’s statement said: ‘Once well enough to do so, [Huw] intends to respond to the stories that have been published.’

Wilson observes: ‘Were a privacy claim to succeed, which is unclear on the present facts, a damages payment could be significant, perhaps even eclipsing phone hacking awards. The consequences of the Sun’s story have been devastating for Edwards who has ended up in a psychiatric hospital. Perhaps more importantly, a serious interference with privacy rights might call into question the government’s decision to abandon Part 2 of the Leveson Inquiry into the conduct of the press.’

As to the lessons from the collateral damage of the Sun’s approach to this story, Wiggin notes: ‘The case illustrates that informed and accurate journalism, where individuals named are given a proper right of reply, is in the public interest and will avoid stoking the fires of keyboard warriors turning detectives desperately searching for the big reveal.’

Case of unfair treatment?

It is not just media lawyers whose attention has been grabbed by this episode. Karen Jackson, principal at employment law specialists didlaw, questions whether Edwards has been fairly treated.

‘In the context of exploring disciplinary issues, suspension is never a neutral sanction,’ Jackson says. ‘Employment tribunals have repeatedly stated that it should only be used where absolutely necessary, for example to protect other employees.’

Given that the conduct alleged was not recent, ‘suspension seems draconian’, she notes. ‘For a suspended employee it is very difficult to come back from suspension… as the suspendee you will feel that your cards have been marked. When suspending an employee with known mental health issues an employer ought to employ extreme care.’

Of the BBC’s own investigation, she says: ‘It is vitally important that any investigation is carried out impartially and, as far as possible, confidentially.’

What if Edwards is exonerated by an investigation? ‘If he alleges that his suspension has destroyed his career he may have a valuable claim against the BBC,’ Jackson concludes. She adds that it would be very hard for a fair process to proceed if Edwards is unable to take part in it on health grounds. The investigation might therefore need to be delayed, she adds.

Stephens concludes that the BBC may have to reform HR procedures which have fallen short in a matter that involves one of its ‘stars’. ‘Part of the problem is [that] inside the BBC it’s recognised that HR doesn’t “work” at that level.’

Viewed in the round, Stephens concludes, the Sun’s stories and the BBC’s response look like ‘a confluence of cockups – a crisis that spiralled out of control’.