As civil legal aid withers away across England and Wales, the Law Society is calling for fees to be reviewed and simplified urgently so that they properly reflect costs

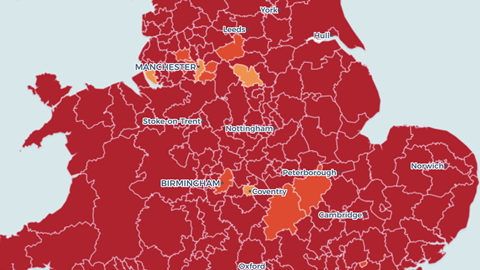

Shocking infographics illustrating the growth of ‘advice deserts’ in community care, education, housing, welfare, and immigration and asylum are the centrepiece of a new campaign on the legal aid crisis.

Analysing data from the Legal Aid Agency’s directory of providers and the Office for National Statistics, the Law Society’s maps show that across England and Wales:

- 52m (88% of the population) do not have access to a local education provider;

- 47m (78%) do not have access to a local welfare legal aid provider;

- 40m (67%) do not have access to a local community care legal aid provider;

- 38m (63%) do not have access to a local immigration and asylum legal aid provider; and

- 23.5m (39%) do not have access to a local legal aid provider for housing advice.

Society president I. Stephanie Boyce said: ‘Behind each statistic is a child not getting the education they need, a family facing eviction, fighting for welfare benefits to stay afloat in these turbulent times or a person denied a say in how they are cared for.’

However, the Ministry of Justice takes issue with the Society’s infographics, which show providers by local authority area. A spokesperson told the Gazette: ‘It is misleading to compare legal aid services to local authority areas as that is not how provision is set.’

The ministry claimed that ‘everyone in England and Wales is able to access help and advice either face-to-face or through the Civil Legal Aid telephone service. The Legal Aid Agency keeps availability under constant review to ensure that every person has access to advice when they need it’.

The MoJ argued that legal aid is one part of a much broader support package. Last year the department announced a £3.1m grant to provide free legal support to litigants in person. Law centres and advice organisations were given £5.4m to remain operational during the pandemic and increase capacity to meet growing demand for social welfare advice.

For all the MoJ’s protestations, there is no doubt the sector is shrinking. The MoJ’s own data shows that in 2012 there were 2,129 civil legal aid providers, with a total of 3,242 offices. Last month, there were 1,401 providers, with a total of 2,258 offices.

A major cause of the shrinkage is, of course, fees. By the time the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO) came into force, fixed or ‘standard’ fees became the norm in most areas of civil legal aid. Initial fixed-fee calculations were based on an average rate of hourly rate spend from a mixed caseload – what the Society calls a ‘swings and roundabouts’ approach. In some simpler cases, providers were rewarded with a surplus. In complex cases, they lost out. Overall, they should average out.

All civil legal aid fees were cut by 10% in 2011. LASPO also significantly narrowed its scope. ‘Although the introduction of fixed fees was originally said to be fair on a “swings and roundabouts” approach, the fact that only complex cases remained in scope with large amounts of simpler work taken out of scope, meant providers were disadvantaged in the absence of any compensating increase in fees,’ the Society says.

Chancery Lane recommends reviewing and simplifying fee structures to reflect costs, as well as a system to uprate fees by inflation. Its report outlines other recommendations, such as mapping the complex system of contracts as they apply to firms seeking to provide different types of civil advice, and assess the barrier to entry that the contracting process presents.

The Society says the standard contract terms and provisions, along with practice area-specific provisions, run to over 200 pages: ‘Combined with a range of separate information on fees listed in statute (2013) and how costs can be recovered – much of which is difficult to find and interpret – the contracts and associated detail present an administrative burden.’

The Society is not alone in its concerns about sustainability. The Commons justice select committee, which conducted an extensive inquiry into the future of legal aid, concluded that sustainability issues for civil legal aid providers were ‘sufficiently serious’ to justify overhauling the system.

The results of the Legal Aid Practitioners Group’s legal aid census, the first detailed exploration of the financial and other pressures forcing lawyers to give up publicly funded work, will be published later this year.

The government, which is conducting its own review of civil legal aid sustainability, should take advantage of this growing body of evidence. Millions, as the Law Society’s maps show, depend on it.

18 Readers' comments