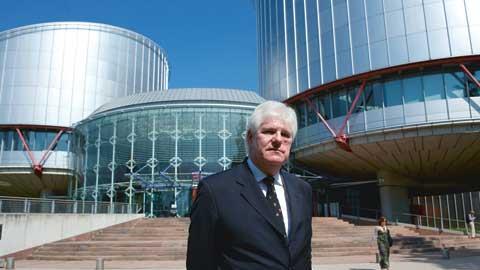

The UK’s judge at the European Court of Human Rights explains how it ‘insures’ nations against ‘backsliding into totalitarian government’.

‘The Strasbourg court is no longer like some satellite in outer space,’ the UK’s judge at the European Court of Human Rights, Paul Mahoney, tells the Gazette. Its rulings have become ‘almost the common law of Europe’, he says, as the 47 member states of the Council of Europe (CoE) integrate them into their national laws.

That is a bold statement given the UK coalition government’s repeated threats to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights (the convention), which it is the court’s responsibility to enforce. The government is regularly incensed by judgments from Strasbourg, where the court is based, allowing ‘hate preachers’ to appeal their deportations (for example). Another ruling, saying that a blanket ban on prisoners voting was unlawful, even made our prime minister feel ‘sick’, or so David Cameron complained.

Mahoney, who replaced Sir Nicolas Bratza in November 2012, has little patience with such ‘little England views’. He says: ‘The UK is strong enough to absorb the flea bites of judgments that go against us. Our staying within the system is good news for Europe, in particular for member states that, unlike the UK, do not have a history of democracy behind them. The UK is a role model for the democratic protection and promotion of human rights.’

He adds: ‘Human rights are not political. The left wing has no monopoly on them. There should be an open debate, in the press, in parliament and in public.’

Fighting talk, indeed, but then Mahoney has been at the Strasbourg court since 1974, when he moved to the city for a ‘two-year sabbatical’. Whenever subsequently he was tempted to move back to London, ‘I was outvoted by the family’, he says.

Mahoney says that the court was very different back in 1974. The CoE then comprised a mere 10 member states, and the court, which had by then only heard a handful of cases, employed just 30 staff. Mahoney was recruited to help handle the first British case to come before the court, where a prisoner had complained about interference with his mail.

He says: ‘The judges in 1974 had lived through the second world war. The Nazis had interned some of them, others had been in the resistance or armed forces, while still others had carried out investigations at concentration camps. They were not in Strasbourg to split hairs. They knew the value of human rights and what happens when states turn their backs on them.’

The court moved in 1994 to a building designed by British architect Richard Rogers. Mahoney notes ruefully: ‘Richard Rogers is no fan of air conditioning. We now run cold water through the radiators.’

The court currently employs 700 staff, including 450 lawyers, and has a backlog of around 150,000 cases. The backlog came about because the court’s caseload increased beyond recognition following the fall of communism in 1989 and the influx of former eastern bloc countries – including Russia – signing up to the convention. The CoE now protects the human rights of some 800m European citizens, from Iceland in the west to Russia’s Pacific shore in the east.

While Mahoney tells the Gazette that it is not going to happen, the backlog of cases would be cleared quickly if member states increased the court’s budget 10-fold to create a ‘monster court’ with 10 times as many judges. He then makes a brave prediction. ‘The backlog will be gone by 2015,’ he says. ‘Our objective is that for every case that comes in, another will go out.’

How is that to be achieved? ‘Protocol 14,’ he replies. He explains that the great majority of cases

are unmeritorious or, in that they are similar to many other cases, repetitious.

In 2010, Russia finally agreed to ratify Protocol 14, which contains provisions to allow the court to deal more quickly with such cases. These provisions include a system of sifting so that cases that should be dismissed are quickly identified. Crucially, Protocol 14 also allows one judge to sit alone to decide on these cases, whereas previously three judges were required; that has effectively tripled the number of cases that can be decided in any period.

Can he give an example of repetitive cases? Mahoney replies: ‘There are 3,500 prisoners in British jails with outstanding claims around their right to vote following Strasbourg’s ruling in 2005 that a blanket ban on their voting is unlawful. There are so many outstanding claims because there are so many different elections that they may be entitled to vote in – such as local elections, the general election, European elections, by-elections. The court is considering special procedures for accelerating these cases.’

He adds that it is ‘unfortunate’ that prisoner votes have received so much publicity. ‘Other countries, such as Italy, have introduced new rules over prisoner voting,’ he says, ‘and the world didn’t end. The UK should bite the bullet and move on in the interests of European justice as a whole’.

What does he say to complaints that Strasbourg overrides the sovereignty of parliament? He replies: ‘A parliamentary majority would seem to imply a respect for democracy, but that isn’t always the case. Adolf Hitler and, more recently, Morsi in Egypt, were both democratically elected. To ensure the protection of individuals and institutions, you need some sort of international guarantee outside the national system. That is what the CoE and the court do. They are a kind of insurance policy against backsliding into totalitarianism.’

The coalition government has formed a working party to consider a UK bill of rights to replace the Human Rights Act (HRA). Is that a retrogressive step? ‘Very much so,’ says Mahoney. ‘Before the HRA, Strasbourg was a kind of constitutional court for the UK because there was nothing within the domestic system to deal with alleged violations of the convention. The UK was accused of lots of breaches and was constantly appearing before the court.’

He adds that since the convention has been ‘repatriated’ to the UK by enshrining it in the HRA, only the ‘odd case’ still goes to Strasbourg, which in most cases rules in favour of the UK. If the HRA were to be scrapped, he says, every case claiming a breach of the convention would – as before – have to be heard in Strasbourg. The analysis of the convention, as manifested in the HRA, by British judges in British courts also has had

the advantage of creating a huge and useful body of UK case law, he says.

The member states of the EU are all signatories to the convention and now the EU itself – its parliament and other institutions – are also acceding to it. How significant is this development? Mahoney replies: ‘EU legislation controls many aspects of our lives. If national laws are subject to Strasbourg, why shouldn’t EU law be accountable, too?’

With the EU’s accession to the convention, there will be an EU judge sitting in the Strasbourg court alongside judges from the member states. The court, through its closer collaboration with the EU, will be able to guarantee EU citizens a degree of external international control against any excesses from Brussels, he says. He stresses that the Strasbourg court and the EU’s top court, the Court of Justice of the European Union, already meet once a year to make sure that they don’t ‘stand on one another’s toes’.

The convention and the Strasbourg court, Mahoney concludes, constitute ‘an organic system that is evolving all the time and inevitably there are going to be mistakes. The British are just as European as the populations of the other member states, we just have a different view of the speed of integration.

‘My grandfather and father fought in the first and second world wars respectively, but my and subsequent generations have never been called upon to fight in Europe. Those people who criticise Europe’s powers might care to ponder that.’

The Council of Europe and the Strasbourg court – a potted history

The CoE was founded in 1949 amid the ashes of the second world war, with the UK one of its most committed supporters. It aims to ensure, through respect for human rights, that Europe never again faces the mass slaughter and genocide experienced in the two world wars.

Countries become member states of the CoE by signing up to the European Convention on Human Rights. The convention, which came into force in 1953, lays out the fundamental rights to which all humans are entitled, simply because they are humans, irrespective of their nationality, religion, sexual orientation or disability. These rights, among others, include the rights to life, liberty and a fair trial.

The European Court of Human Rights, whose role it is to enforce the convention, was established in 1959 in Strasbourg. Each member state nominates three of its national judges, one of whom is then elected by a vote of the parliamentary assembly of the CoE to hear cases before the Strasbourg court. There are currently 47 judges at the court, one from each member state.

The CoE should not be confused with the EU, which is an economic association of 28 countries dedicated to the promotion of trade and the free movement of people.

Jonathan Rayner is Gazette staff writer

No comments yet