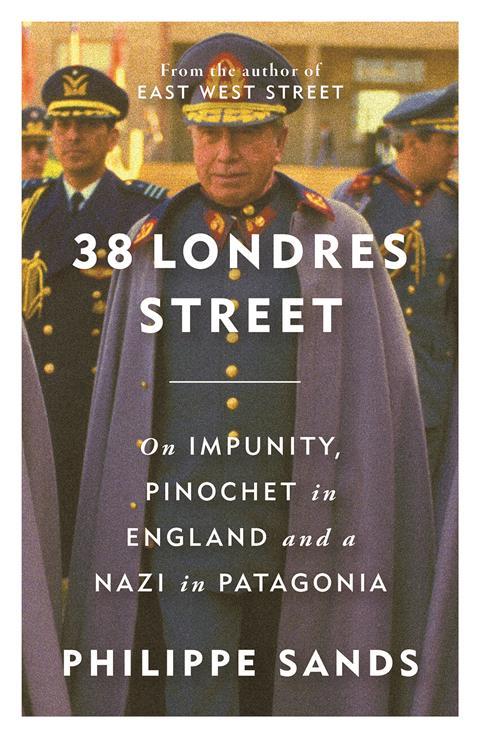

38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia

Philippe Sands

£25, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

★★★★★

In the interests of full disclosure, I should begin this review by explaining that Philippe Sands and I both studied for the LLM in Cambridge in 1982. Subsequently, Philippe and I jointly presented a course on public international law to students of Pepperdine University Malibu Beach (but unfortunately in its Regent’s Park campus). Since then, sadly, I have had little contact with Philippe, other than brief exchanges at various memorial services.

Our LLM course in 1982 was really quite special. I believe that we both elected for option (d) of the LLM which characterised our LLM as being in public international law. Among the faculty were: the late Sir Elihu Lauterpacht (the son of Hersch Lauterpacht); Professor Derek Bowett, Whewell Professor of Public International Law; Sir Christopher Greenwood (the former British judge at the International Court of Justice and current Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge), described by Philippe in his book as ‘a fine advocate, of a conservative disposition’, to name but a few. ‘Chris’ Greenwood taught us the law of armed conflict. For those lectures, I sat next to William Rogers (a mature student), the former US secretary of state and author of the famous Rogers Plan, which was intended to bring peace between the Arabs and the Israelis. We had weekly seminars with Professor Bowett in the Lauterpacht Room in the Old Squire Law Library. Each week one of us had to present a paper to the group and Professor Bowett on a topic relevant to the curriculum we were studying which was titled ‘The Law of Peace’. I distinctly recall Philippe delivering a lecture on baselines in the law of the sea (a mechanism whereby states can measure the extent of their territorial waters). Philippe’s presentation stood out way above the others.

Philippe has not only had a meteoric career as an international lawyer in recent years (the Chagos Islands to name but one landmark case), he has also had a prolific career as an author. 38 Londres Street is the third volume of a trilogy which began with his seminal work East West Street, the winner of the Baillie Gifford prize for non-fiction.

In 1998, Philippe was asked to act for Augusto Pinochet (pictured above), Chile’s former autocratic president, in respect of his claim for diplomatic immunity against charges of genocide and crimes against humanity. Philippe tells us that in order to avoid the risk of divorce, he declined the brief and instead made submissions on behalf of Human Rights Watch. He overcame the strictures of the ‘cab rank’ rule and relied on an exemption that he would be ‘professionally embarrassed’ were he to accept the brief.

Philippe weaves together the lives of two disparate, but in an evil way, connected individuals, namely General Pinochet and a Nazi war criminal, Walther Rauff, who sought sanctuary in Chile and who was close to Pinochet. In 1998, General Pinochet travelled to London for medical treatment, and thus began a protracted campaign by various parties to arrest him on what were then novel charges of crimes against humanity and genocide. The legal issues that arose are well told by Philippe in his account of what transpired. The relatively recent arrest warrants issued by the International Criminal Court against Israeli politicians and Hamas terrorists bring this aspect of international law into sharp contemporary focus.

Parts of the book read like a spy thriller and in other sections the reader is granted a rare and privileged glimpse into the inner workings of the former House of Lords Appellate Committee, now replaced by our Supreme Court.

It is estimated that Rauff was responsible for the murder of 97,000 Jews. He invented a sinister mechanism for exterminating the Jewish race, namely gas vans camouflaged as ambulances. The Israeli secret service Mossad determined that Rauff should either be executed or brought to Israel for trial. This is what Philippe tells us transpired when Mossad agents visited Rauff’s house in Chile: ‘With two executioners in the parking lot near the house, Rauff failed to appear. The two returned the next day. Rauff again failed to appear, so the two approached the house. Nena (Rauff’s partner) suddenly emerged alerted by Rex (Rauff’s German Shepherd). At the front gate, when she blocked their entry, they enquired in Spanish about a random person. The woman replied rudely and raised her voice aggressively – “What do you want!” she started to shout angry and impatient, in Spanish “You have nothing to look for here”.

‘At that point the dog went ballistic, barking loudly and continuously and running around. The assassins worried about the neighbours, and weren’t sure whether Rauff was inside. The dog continued to bark, Nena shouted ever louder. They thought about entering the house to “eliminate” Rauff, then decided to abort the operation.’

Oddly enough, Mossad neither kidnapped nor assassinated Rauff for reasons that will never be clear, notwithstanding the horrific crimes that he committed. He died a natural death in Chile but not before he resorted once again to commissioning (this time refrigerated) vans to transfer detainees at the request of Pinochet to and from 38 Londres Street, which was a place of detention and torture in Santiago used by the Pinochet regime.

Sir Christopher Greenwood was instructed by the government of Spain. In a recent interview, he recalled: ‘I was paid by the Crown Prosecution Service, but the CPS acts for the requesting government in an extradition case. The Pinochet case obviously attracted an enormous amount of attention. It was an extremely challenging case to do.’

38 Londres Street flips between attempts to bring Pinochet to justice and determining whether Rauff was complicit in Pinochet’s crimes in Chile.

The House of Lords had to decide whether Pinochet had immunity for torture and the disappearance of his political opponents after the 1973 coup that brought him to power. The key point was whether such crimes could be considered part of Pinochet’s official functions. The Lords’ initial decision not to grant immunity was challenged on the grounds that one of the judges, ‘Lennie’ Hoffmann, was conflicted due to his links to Amnesty International, one of the participants in the application to the extradition hearing. The Lords subsequently determined that Pinochet had immunity in respect of most of the charges.

Ultimately, Pinochet did not face justice in Spain (which country had applied for his extradition), claiming dementia and general poor health. He was freed on medical grounds in 2000. Hoffmann years later mused that ‘Pinochet “conned” Straw (the home secretary at the time) into believing he had Alzheimer’s’. It’s also possible that the leniency applied to Pinochet was attributable to the debt of gratitude owed to him and Chile by Margaret Thatcher for the help he gave the UK during the Falklands War.

The Pinochet affair was the first time a former head of state had been arrested on the basis of the principle of universal jurisdiction applicable to international crimes.

The book contains many fireside chats with elderly lawyers (frequently in Hampstead) and we are even treated to the spectacle of Philippe and Lennie Hoffmann being locked in the grounds of Kenwood House following an evening stroll. We are told that Philippe tore his trousers climbing over the railings, but was impressed that a retired judge in his 80s was able to hurdle over six feet of metal with sharp prongs relatively athletically.

Rauff died of natural causes in 1984. Pinochet died in 2006.

Following Pinochet’s return to Chile, remarkably the UK government paid him £980,000 for his legal costs, notwithstanding the murder, torture and disappearances that he undoubtedly authorised.

Stephen D Sutton is principal of Suttons Solicitors and International Lawyers, London W1

No comments yet