As the government battles to fulfil its pledges on tackling modern slavery, Grania Langdon-Down discovers that professionals are also under huge pressure to help crack down on such criminality

Theresa May said in 2016 that modern slavery is the ‘great human rights issue of our time’. The PM was determined to make it a ‘national and international mission to rid our world of this barbaric evil’. But last year, nearly three years after the world-leading Modern Slavery Act 2015, practitioners and campaigners had to fight a succession of landmark cases through the courts to protect trafficking victims against government policies on legal aid, immigration and the benefit system. British citizens are now the largest group of potential modern slaves flagged to the National Referral Mechanism, the numbers driven up by teenage victims of violent ‘county lines’ drug gangs. The government has acknowledged the MSA needs updating to re-establish the UK as a world leader in tackling modern slavery and protecting victims. But it is also time for lawyers to step up and become agents of change.

The UK led the world when it enacted the Modern Slavery Act (MSA) in 2015. Yet modern slavery is going on every day in the UK – hidden in plain sight in nail bars, car washes, among night cleaning staff, in food production and in domestic servitude.

The Global Slavery Index puts the number of people trapped in modern slavery in the UK today at 136,000, much higher than a government estimate of up to 13,000.

Yet more than three years on, thousands of companies are still failing to publish a modern slavery statement identifying how they are tackling the risks in their domestic and international supply chains.

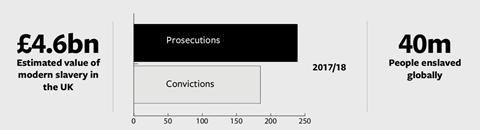

Prosecution and convictions for slavery are up but victims of trafficking and slavery are also still being prosecuted, despite a series of Court of Appeal judgments criticising police, prosecutors and defence lawyers for failing to identify and act upon claims of trafficking and forced criminality.

In 2017, 5,145 potential victims were submitted to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), the framework by which potential victims of human trafficking and modern slavery are identified and supported, a 35% increase on 2016. British citizens now account for the largest group (820), driven by an increase in referrals of teenagers exploited by violent ‘county lines’ drug gangs, from 255 in 2016 to 677 in 2017.

Globally, modern slavery is estimated to involve 40 million people. That brings into sharp focus a growing debate internationally about the role of lawyers. Should they just advise on the law – the bare minimum – or should they be encouraging a culture of compliance that drives up standards?

Tony Fisher, chair of the Law Society’s Human Rights Committee, says the question of whether legislation such as the MSA and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights are moving the boundaries of legal advice is being keenly debated around Europe. ‘A lot of EU bars are against this,’ he says. ‘My personal feeling is that this is a space where lawyers can have a beneficial influence on clients, and help secure greater protections of fundamental rights.’

Every time you introduce a rigorous piece of legislation, it puts a big compliance burden on companies. But I am definitely not sensing clients see this as just red tape

William Boddy, McGuireWoods

This year could be one of significant change to the UK’s modern slavery strategy, if the government lives up to its pledges to provide better protections for victims. Last year, practitioners had to bring a series of landmark cases to force changes to government policy.

The Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act has been tasked with considering: the role of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner; transparency in supply chains; independent child trafficking advocates; and criminal justice aspects including – the definition of exploitation; reparation orders; and the section 45 statutory defence open to victims forced into criminality.

Led by Frank Field MP, Baroness Butler-Sloss and Maria Miller MP, the review is on track to report its findings to home secretary Sajid Javid by the end of March.

Running alongside the review is the Home Affairs Select Committee inquiry into modern slavery, chaired by Labour MP Yvette Cooper. It is looking at the difficulties experienced by victims in accessing support; the challenges posed by increasing numbers of victims in the UK; the impact of the government’s recent reforms of support provision; and the criminalisation of victims, including children involved in county lines exploitation.

There are also two private members’ bills going through the parliamentary process to strengthen the rules around transparency in supply chains and to improve the package of protections for victims.

The review’s first interim report was published just before Christmas and focused on the role of the anti-slavery commissioner.

That role’s first incumbent, Kevin Hyland, resigned last May to take up a role with a charity. While he praised prime minister Theresa May for her ‘personal leadership’ in the fight against modern slavery, he also cited government interference. ‘At times independence has felt somewhat discretionary from the Home Office, rather than legally bestowed,’ Hyland wrote.

The interim report recommended the job description be redrafted so the role has a sponsoring minister in the Cabinet Office rather than a Home Office line manager. However, Field tells the Gazette that the home secretary has just gone ahead with the appointment process. ‘We are waiting for the name,’ he says.

The review’s next report is on the section 54 requirement for organisations which have a turnover of £36m and do all or part of their business in the UK to publish annual transparency statements. Known as modern slavery statements, these should set out what the organisation is doing to stop forced labour practices occurring in their business and supply chains.

Last October, the Home Office wrote directly to chief executives of 17,000 businesses telling them to be more open about the risks in their supply chains, or risk being named as in breach of the law. It said only an estimated 60% of organisations in scope have published a statement, with many failing to meet even the basic legal requirements.

FTSE 100 ‘TICKING THE BOX’

-

The Guardian reported in December that the NHS has been using medical gloves made in Malaysian factories where migrants were allegedly subjected to forced labour, forced overtime, debt bondage, withheld wages and passport confiscation.

- The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre’s third annual report on the FTSE 100 found most companies still publish generic statements, with ‘only a handful of leading companies’ demonstrating a genuine effort to identify and mitigate risks.

- The French duty of vigilance law has significant penalties but is drawn much tighter than the UK legislation, so it only catches an estimated 200 of the largest companies.

- On 1 January, Australia’s Modern Slavery Act became law. It also relies on ‘naming and shaming’ to drive compliance with statements rather than introducing penalties. But New South Wales has passed its own law, with penalties of up to A$1.1m for businesses that do not comply.

- Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer won the Law Society’s 2017 Excellence Award for its work bringing and enforcing civil claims for victims of domestic servitude. Paul Yates, head of pro bono, says: ‘The biggest gap is in enforcing those claims in the county courts. It is very common for traffickers to ignore awards and the enforcement system is much more complicated to navigate than it ought to be.’

Guidance to the act says statements ‘should’ contain information on the company’s policies, due diligence processes, identification of risks and steps taken to mitigate them, and training. Campaigners want the content to become mandatory. They also want public bodies to be brought into scope and to use their extensive procurement as leverage.

Ensuring compliance is a key role for in-house and external lawyers. Peter Carter QC, one of the independent review’s expert advisers, told a recent Law Society seminar on modern slavery that the review team had sent out a general request for information about problems lawyers were encountering in advising qualifying companies.

‘We did not receive a single response,’ he said. ‘We didn’t want the names of clients. We just wanted to know how you interpret the statute, which all of us struggle with.’

Carter said he personally believed section 54 statements were weakened by no central database, no penalty for non-compliance and no effective enforcement. He suggests statements could be made part of the Companies Act so they have to be included in annual reports with a criminal sanction if they are not.

Joss Saunders, company secretary and general counsel, Oxfam GB, says the statements were ‘designed to be a nudge – and it has nudged some companies in very positive ways. But the content should now be made mandatory’.

Oxfam GB’s own statement is 32 pages and is open about the painful period it has been through. It emphasises the importance of learning from its safeguarding work on sexual abuse and exploitation.

‘You have to ask the tough questions,’ says Saunders. ‘Who is cleaning your office at 10pm? Are they being paid properly, have they control of their passports?’

The government’s ‘hostile’ approach to immigration is at odds with the needs of foreign nationals trafficked here. The Home Office has promised to create a single, expert case working unit to separate NRM cases from the immigration system and a spokesman tells the Gazette that the transition will ‘begin shortly’.

The Home Office also says that support for victims who receive a decision from the NRM that they have been trafficked or used for forced labour will soon increase from 14 days to 45 days, and those who receive a negative decision will see an increase of further support from two days to nine days.

The statements were designed to be a nudge – and it has nudged some companies in very positive ways. But the content should now be made mandator

Joss Saunders, Oxfam GB

This is still too short a time, argues Nusrat Uddin, a solicitor with Wilson Solicitors who led last year’s successful challenge to the Home Office decision to cut weekly benefits to asylum-seeking victims of trafficking by over 40%. She says fear of deportation or removal was one of the crucial factors behind victims’ reluctance to report crimes.

When it comes to the criminal justice elements of the legislation, Field says this goes to the heart of the act: ‘We are very anxious to gain the view of lawyers and judges on how well this act works in bringing slave owners to justice.’

Philippa Southwell is a consultant with Birds, where she heads the Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery Department. She acts for victims who are being prosecuted for criminality committed while under the control of violent gangs and has led a series of successful appeals against convictions, some many years old.

Where Southwell has not been successful is in getting convictions of drug mules quashed. She says: ‘What the Court of Appeal says is that, we can see your client was a victim of trafficking but there will be situations where the criminality is so serious, it will always be in the public interest to prosecute.’

She says the section 45 statutory defence under the MSA has made a difference as the previous defence of duress was very hard to prove. But she wants schedule 4, which lists about 100 offences where the section 45 defence cannot be raised, to be reviewed.

There are significant issues with the NRM over delays and negative determinations: ‘You regularly see judges and lawyers, both prosecution and defence, who don’t know they can challenge a negative trafficking finding and instead advise the victim to plead guilty.’

Last October, a drug dealer who trafficked three children including a teenage girl to use in a ‘county lines’ crack and heroin selling ring was been jailed for 14 years after a landmark prosecution.

Southwell says the county lines exploitation is driving an alarming rise in the numbers of potential trafficking victims being referred to the NRM. ‘Are we being a bit trigger happy with NRM referrals? Possibly,’ she says. ‘That type of exploitation needs to develop a legal framework. We can see the Crown getting very uncomfortable with section 45 defences being raised in circumstances where young boys previously seen as problem children with five or six convictions for possession with intent to supply are now being viewed as victims.’

There are two layers of protections for victims to stop a prosecution and Southwell feels she has failed if it goes to trial and she has to use the section 45 defence.

‘It is a terrible thing to say but the reality is that, given the fixed-fee structures within criminal legal aid, practitioners aren’t paid to make lengthy representations,’ she says. ‘This is why we see so many individuals being prosecuted or advised to plead guilty.’

Modern slavery cases are among the most challenging for the CPS, says Malcolm McHaffie, deputy chief Crown prosecutor and its lead on modern slavery. He says the CPS is looking at further training for prosecutors to help them recognise signs that a suspect may be a victim of trafficking or slavery.

The Court of Appeal held last year that the legal burden falls on the prosecution to disprove a section 45 defence beyond reasonable doubt. McHaffie says: ‘This is often difficult or impossible to do, as it involves proving a negative in respect of facts which are usually outside the knowledge of the prosecution. It is a concern that the defence may be unscrupulously used by non-genuine victims to avoid conviction.’

There are other civil aspects to trafficking cases where practitioners are trying to achieve remedies for victims.

In 2016, a Kent-based gangmaster couple agreed to a landmark settlement resulting in a substantial payment to a group of migrants who had been trafficked to work on farms producing eggs for high street brands.

The deal reached with six Lithuanian chicken catchers, represented by Leigh Day, was the first settlement of a claim against a British company in relation to modern slavery. Eleven other claimants are now bringing similar cases against the company, DJ Houghton Catching Services Ltd, director Darrell Houghton and his wife, Jacqueline Judge, the company secretary.

Mary Westmacott, associate solicitor with Leigh Day, says a four-day trial is listed in the High Court on 18 February where the 11 claimants will be seeking summary judgment as regards the company’s liability for alleged contractual breaches. There will also be a preliminary issue trial on the couple’s personal liability for those alleged breaches. The pair deny liability.

Westmacott says there are wider problems for victims working in small companies operating below the radar with few assets. She adds: ‘We have to rely on a variety of torts which might not be a perfect fit. But this is a unique situation and deserves its own remedy because of what they have been through.’

Oxfam’s Saunders helped to set up the website justlawyers.net, an initiative for in-house lawyers which sets the challenge: ‘Are you just a lawyer, or a Just Lawyer?’ He says: ‘There is a movement in law in recognising companies can operate in ways which are profit-making but also good for society. Modern slavery is a clear example.’

It is also important, says Field, to be bold in stepping up the legislation to put the UK back in poll position as a world leader in tackling modern slavery. ‘I can’t see any government not wanting to put the legislation in place to do that.’

Time will tell.

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet