Nazi war criminals: why so many ‘got away with it’

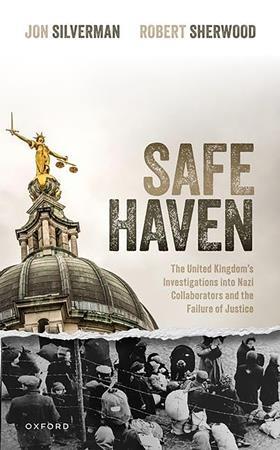

Safe Haven: The United Kingdom’s Investigations into Nazi Collaborators and the Failure of Justice

John Silverman and Robert Sherwood

£30, Oxford University Press

★★★★✩

One indisputable fact about the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany and its allies is that they were not the sole responsibility of senior politicians and generals. The Holocaust required the active connivance of thousands of soldiers and public servants, while many other war crimes were committed upon the whim of individual soldiers or commanders.

Such was known well before the war ended, and from a comparatively early stage in hostilities Allied forces began to compile evidence with a view to eventual prosecutions. Those efforts led to Nuremberg (pictured) and other lesser-known trials more local to the areas under Allied control.

In post-war Britain, however, the issue of Nazi war crimes soon slipped in terms of priority; ironically, while public awareness of the Holocaust began to increase. It took until 1991 for an act of parliament to be passed enabling prosecutions of war crimes beyond normal British jurisdiction (the War Crimes Act 1991). This resulted in a solitary conviction, the former Belarusian Nazi collaborator Anthony Sawoniuk. The majority, bluntly, got away with it.

This book by John Silverman and Robert Sherwood, respectively a journalist and a legally qualified police officer, seeks to explain this paucity of convictions in the face of the extensive documentary and witness evidence of Nazi war crimes. They carefully trace the history from wartime through to the 1991 act and Sawoniuk’s subsequent conviction.

The problems they identify include the stringent evidentiary requirements of the criminal law and a lack of resources throughout. The rise of Cold War tensions also hampered co-operation with Soviet authorities, who held a substantial amount of evidence regarding individuals who had fled to the west. (One should also cite NATO’s desire to rehabilitate the Wehrmacht’s reputation to gain public support for building up a West German army.) Inevitably, as the years passed official ennui set in and both potential defendants and surviving witnesses died off.

Even when parliament finally passed the 1991 act and a specialist police unit was set up, arbitrary constraints were imposed in the form of a policy to concentrate on defendants who had been in a position of authority in wartime and where the victims were Jewish. Neither constraint was required by the act.

The authors draw upon extensive research and present their arguments forensically. The book is not only of historical interest, but also offers valuable insights for those seeking justice for later atrocities, of which there have been and continue to be depressingly many.

James Wilson is an independent legal author. His most recent book is Lord Denning: Life, Law and Legacy (Wildy, Simmonds & Hill, 2023)

No comments yet