‘Mounting hostility toward human rights lawyers’ in Northern Ireland threatens to spills over into violence.

Today is the day of the endangered lawyer.

I stand by the office printer and a death threat notice drops quietly on to the collating tray.

‘Information has been received that loyalist paramilitaries have gathered information on the movements of Patrick Murray and may intend to cause him harm at an unknown time. Police believe this refers to you. Please review your personal security.’

The next sheet of paper has a picture of three men, each with a ‘target’ superimposed over their heads. Evidently, I am not Patrick Murray (Pádraig Ó Muirigh) and there is no image of me with a target over it. Yet the moment provides a small insight into the life of some Northern Ireland solicitors.

Attacks on Northern Ireland solicitors and law officers in press and parliament mean lawyers face harassment and credible death threats such as this.

Speeches in the Commons criticising solicitors and law officers, implicitly or explicitly linking them personally to republican clients, have increased.

Examples that cause concern included Sir Henry Bellingham, who insisted Northern Ireland’s then-DPP Barra McGrory was, ‘prepared to move away from credible evidence to political decision-making’. Newbury MP Richard Benyon, also seemed to focus on McGrory, when he mentioned ‘extreme nationalist-leaning individuals in the Northern Ireland justice system’. (McGrory, in fact, mounted five times the number of cases against alleged paramilitaries as soldiers.)

The situation is sufficiently serious to receive attention from a US bar association, and is the subject of reports to a UN human rights rapporteur.

‘It’s become more difficult in recent times,’ Ó Muirigh tells the Gazette. He links the rise in online threats to a personalised campaign by ‘right wing tabloids’, prime minister Theresa May’s decision to single out ‘human rights lawyers’ in her last party conference speech, and the activity of parliamentarians like Benyon.

Ó Muirigh was one of several solicitors whose family homes (value and rough location) were highlighted in a December 2016 Sun article that is now the subject of legal action. The offices of the firms were photographed.

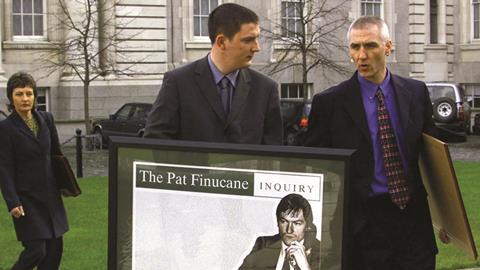

But despite the notorious murders of Northern Ireland solicitors Pat Finucane (shot in front of his wife and children in 1989) and Rosemary Nelson (killed by a car bomb in 1999), UK government ministers have failed to respond to correspondence raising concerns for the position and safety of Northern Ireland lawyers.

The attorney general has replied to private correspondence from law officers, but he and relevant ministers decline to publicly confront parliamentary colleagues who personally attack lawyers and law officers, or to make any statement in support of lawyers singled out for personal vilification.

Benyon’s Armed Services (Statute of Limitations) Bill, though unlikely to become law was presented with arguments that are gaining common currency in parliament and the press, and its basic elements are supported by the Defence Select Committee.

The prime minister’s party conference speech last year also took this line: ‘We will never again – in any future conflict – let those activist left-wing human rights lawyers harangue and harass the bravest of the brave, the men and women of our armed forces.’

Northern Ireland solicitors particularly resent a link being drawn between legacy cases they are handling, and the conduct of disgraced solicitor Phil Shiner - ‘lawyers—sadly, often dishonest lawyers’, in Benyon’s words. It is particularly resented because Northern Ireland solicitors handling legacy cases tell the Gazette they declined to work with Shiner’s firm.

Also resented is the portrayal of several firms as only acting for clients from one side of a divide – republican. (The ‘legal auxiliaries’ of the Sinn Fein-IRA ‘family’ as The Sunday Times Dublin edition puts it.)

That, all point out, is simply untrue.

The firms Madden & Finucane, KRW and O’Muirigh Solicitors, and McGrory all point out that they have consistently acted for clients from all ‘sides’ and ‘communities’ – including soldiers, policemen (and the families of both), secret service, loyalist paramilitaries and unionist politicians.

The president of the 24,000-member New York City Bar Association, John Kiernan, wrote to the prime minister and then-secretary of state for Northern Ireland James Brokenshire in July last year. In the letter, seen by the Gazette, Kiernan raised ‘a series of concerns surrounding the recent climate of intimidation that has been re-emerging for lawyers in Northern Ireland’.

‘It is particularly disquieting that government officials appear to have contributed to this climate of intimidation, both by failing to adequately intervene in response to these threats and by engaging in their own attacks on lawyers,’ he continued.

To date, a reply has not been sent, though Belfast firm KRW is set to submit a freedom of information request related to the correspondence.

Washington-based not-for-profit organisation Human Rights First published a report in June 2017, A Troubling Turn: The Vilification of Human Rights Lawyers in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland solicitors handling legacy cases reference it as the best summary of the growing criticism and attendant risks they face.

‘In recent months,’ the authors note. ‘an atmosphere similar to that which preceded the killing of Finucane and Nelson has returned.’ Nearly 20 years after the Good Friday Agreement, they note: ‘Mounting hostility toward human rights lawyers is threatening to bring political violence back to Northern Ireland.’

Referencing one speech by Conservative MP Sir Gerald Howarth, HRF notes: ‘The attempt to link solicitors and the DPP [Barra McGrory at the time] to the IRA is dangerous.’ Finucane’s murder, it notes, was preceded by Home Office minister Douglas Hogg’s insistence that some Northern Ireland Solicitors were, ‘unduly sympathetic to the cause of the IRA’.

In fact, as Daniel Holder, deputy director of Belfast-based Committee on the Administration of Justice, points out, the UK government and Northern Ireland parties, having endorsed the 2014 Stormont House Agreement, are as a matter of policy committed to facilitating more ‘legacy’ cases. This should be by, ‘acknowledging and addressing the suffering of victims and survivors’, and ‘facilitating the pursuit of justice and information recovery’. At present, he says, ‘resources and powers’ are not made available to achieve that – progress is monitored by the UN, following its periodic 2015 review of human rights in the UK.

Northern Ireland, needless to say, has special and particular concerns when threats and violence seem in prospect. But solicitors working on ‘legacy cases’ are considering a wider context.

For many, the murder of Jo Cox MP is front of mind. As KRW consultant Christopher Stanley puts it: ‘Unregulated social media avenues to vent anger against us may soon result in violent direct action. Those in the public sphere – whether protected by privilege or not – must have a duty of care to both their law officers and their legal profession not to encourage such random outbursts of hatred with its fearful results.’

Endangered lawyers: Climate of intimidation 're-emerging' in Northern Ireland

Death threats, and abuse on the streets and online, follow hostile press and parliamentary comment.

- 1

- 2

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Endangered lawyers: Closer to home than you think

- 4

6 Readers' comments