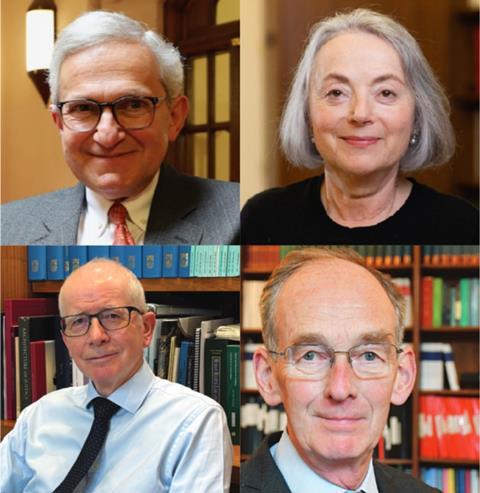

The first week of the legal term has presaged a major reshaping of the senior judiciary. On Monday, Sir Geoffrey Vos announced that he would be retiring in October as master of the rolls. On Wednesday, Dame Victoria Sharp disclosed that she too will be retiring that month as president of the King’s Bench Division. And last Friday, Lord Reed of Allermuir revealed that he would be standing down at the end of this year as president of the Supreme Court.

With Sir Andrew McFarlane retiring as president of the Family Division in April, this is an unprecedented challenge to our system of judicial appointments. It is a bigger realignment of the senior judiciary than we saw in 2000, when Lord Bingham was promoted from lord chief justice to senior law lord, Lord Woolf was moved up from master of the rolls to lord chief justice and Lord Phillips was advanced from junior law lord to master of the rolls.

Crucially, those appointments all took effect on the same day. The three-way shuffle was an inspired move by Lord Irvine of Lairg, who, as lord chancellor, was then responsible for all judicial appointments. But it cannot happen now because candidates must apply for each job individually.

Gone are the days when the lord chancellor’s long-serving, legally qualified senior officials regularly updated the files they kept on all barristers. These were locked away in cupboards fronted with chicken wire, to be consulted before a potential judge was called in for a tap on the shoulder.

The constitutional reforms announced by Tony Blair in 2003 made it impossible for the lord chancellor to continue selecting the judges. But the Judicial Appointments Commission, which took over in 2006, has not been an unqualified success.

Perhaps that is not surprising. The best people to pick and promote judges are the judges themselves. Judging is, after all, their job. But to have given judges control over the commission would have risked creating a self-perpetuating oligarchy – jobs for the boys. So non-judges must be the majority.

A report in 2021 from the Policy Exchange Judicial Power Project recommended increased ministerial involvement, with the lord chancellor being allowed to reject candidates who might ‘undercut settled constitutional fundamentals’. We can only speculate on whether the report’s authors would want a Labour lord chancellor to have such far-reaching powers.

After all, David Lammy and his predecessor Shabana Mahmood have not even managed to find anybody to chair the appointments commission, despite knowing for a year that the part-time post would fall vacant at the end of last month. Lammy has now brought in recruitment consultants and increased the daily rate from £577 to £750. But the job has not yet been readvertised and I would be surprised if a new chair was ready to start before the summer.

Of course, other commissioners will fill in to the extent that they can. But what’s going to be missing in the coming weeks is strategic thinking.

Imagine you are a fairly senior member of the Court of Appeal, perhaps already on the Judicial Executive Board. You know there will be a vacancy in the Supreme Court at the beginning of next year. In fact, there will be two because Lord Lloyd-Jones will be reaching retirement age – for the second time – but you think he will be replaced by somebody with ‘knowledge of and experience of practice in’ the law of Wales – as statute apparently requires.

Do you apply for master of the rolls? President of the King’s Bench? Could you apply for both? And can you try for the Supreme Court as a fallback, given that the court has its own appointments process? Maybe, as a ‘candidate with substantial experience in equity and corporate law’, you have already applied for the seat on the Supreme Court to be vacated in June by Lord Richards of Camberwell.

What you really need is someone with an overview, someone who knows the handful of judges who are appointable to these jobs and can speak to candidates in confidence. Unless the appointments commission chair can manage the process in this way, there is a risk that applicants will be selected for one leadership role one day and offered another top job the day after.

And where will this leave the Court of Appeal? Around half a dozen of its members will be needed for the vacancies I have mentioned already. But if the appointments commission waits until these jobs become vacant, there will not be enough appeal judges in post by the autumn.

Raising the retirement age from 70 to 75 in 2022 allowed Lloyd-Jones and Richards to return. But Vos, Sharp, Reed and McFarlane have all chosen to leave at the age of 70 or 71. If we are to maintain a world-class judiciary, someone needs to get a grip.

joshua@rozenberg.net

4 Readers' comments