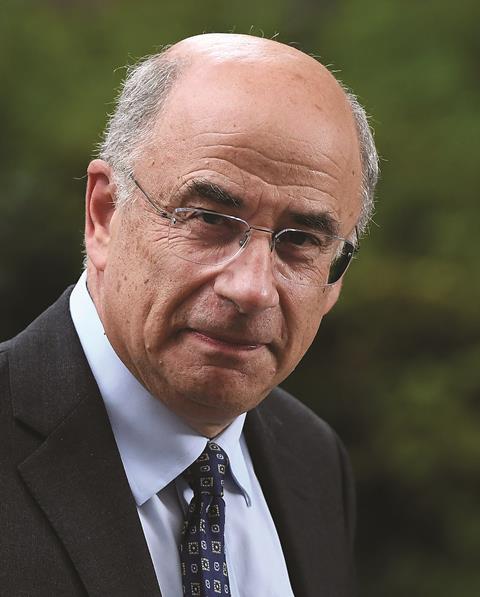

On Wednesday Sir Brian Leveson unveiled the second part of his criminal courts review. Rebuilding the legal aid workforce through annual fee reviews and trainee grants is included in a smorgasbord of recommendations

The second – and final – instalment of Sir Brian Leveson’s criminal courts review arrived last week, containing 135 recommendations to drive Crown court efficiency.

In part one, lest we forget, the former president of the Queen’s Bench Division put forward proposals that would restrict the right to a jury trial – proposals which, to the dismay of the profession and MPs, lord chancellor David Lammy is taking forward (subject to a few tweaks). Part two has received a warmer reception.

Where part one was about policy, part two is very much about process. The latest recommendations cover getting decisions right first time at police and prosecution stage, disclosure, listing and allocation of workload, preparing for the first hearing and ongoing case management, remote participation, hearing processes, and the judicial and legal workforce.

Recommendations to help recruit and retain defence solicitors have gone down well with the Law Society. Immediate past president Richard Atkinson, a criminal defence solicitor, said they are essential to the fairness and efficiency of the criminal justice system.

Leveson notes that the number of criminal legal aid solicitors fell by nearly a third between 2013/14 and 2023/24, from 14,800 to 10,200. The number of duty solicitors has plummeted, from 5,200 in 2017 to 3,900 in 2024. The proportion of criminal legal aid solicitors aged 54 and under has fallen from 79% in 2014/15 to 73% in 2023/24. Leveson notes that in 10 years’ time, those aged 55 or above will be approaching retirement or will have retired.

‘Unless there is a conscious effort to rebuild this workforce to meet this increased demand, I believe the criminal legal aid system is at risk of failure,’ Leveson declares.

He adds that an under-resourced duty solicitor workforce can result in defendants going it alone in court, resulting in longer trials and hearings.

Leveson calls for a ‘targeted and multilayered approach’ to rebuild the workforce as a matter of urgency. To begin with, law firms should be incentivised to support trainees to work in criminal law: a suggestion that appeared in Sir Christopher Bellamy’s criminal legal aid review in 2021.

‘From my engagement with the sector, I understand that there are financial concerns among many criminal legal aid firms that they cannot afford to take on trainees. This is affecting the sustainability of the market and is a concern, especially with data pointing towards the trend of an ageing profession. The key to increasing the workforce is having the space to train them, and that is why I believe the government need to take a dual approach.’

In part one, Leveson recommended the government match-fund pupillages for barristers in criminal law. In part two, Leveson calls for this to be mirrored for solicitors and recommends the government match-fund the police station and magistrates’ court qualifications.

He also wants to see, as recommended by Bellamy, a trainee grant to cover some of the costs incurred by firms when training junior lawyers.

On how to draw people to the profession, Leveson cites successes in the education sector, such as student loan reimbursement schemes for teachers, the Teach First recruitment programme and the ‘Get into teaching’ campaign. ‘In fact, the government is now cutting its recruitment targets for secondary schools by almost 20% as they see strong numbers of applications and better retention of teachers,’ Leveson notes.

He acknowledges that criminal legal aid solicitors are not public sector workers, but believes more work should be done to highlight the value of working in criminal legal aid and offering financial incentives.

He also acknowledges that the government does not have the proverbial ‘magic money tree’. ‘However, I cannot emphasise enough the looming crisis posed by the low numbers of criminal legal aid solicitors and the need to build capacity back into this workforce,’ he says.

'We run the risk of defendants in criminal proceedings not having adequate opportunity to ask questions of their legal advocates beforehand'

Simon Garrod, Chartered Institute of Legal Executives

Leveson calls on the government to commit to annually reviewing legal aid fees, warning that ‘it is not sustainable to retain the current approach whereby only a crisis triggers a reactive response’.

The Law Society does take issue with some of Leveson’s recommendations, such as the provision of legal advice through video-link to people detained in police stations and remote court hearings ‘where people’s liberty is at stake’, Atkinson told me.

Simon Garrod, director of policy and public affairs at the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives, says remote hearings might free up court resources and appear more efficient, ‘but we run the risk of defendants in criminal proceedings not having adequate opportunity to ask questions of their legal advocates beforehand. This is valuable time when outcomes are explained to clients, changes of plea occur, and probation and bail decisions are discussed. Limiting this vital engagement could prove counterproductive’.

Leveson recommends that the Legal Aid Agency change its police station telephone advice contract to give defence solicitors the option to provide initial advice remotely where appropriate. Remote advice, he stresses, would not be appropriate for under-18s, vulnerable people or indictable-only offences. Few available defence solicitors, especially outside working hours, and delays as a result of multiple police station callouts factor into his reasoning.

He recommends a ‘test, learn and cost’ approach for first hearings in the magistrates’ court to be conducted partially remotely by default for defendants appearing in custody.

While the presumption that trials should be conducted in person should remain, police and professional witnesses should by default be allowed to attend remotely. Defendants should only be required to attend a sentencing hearing in person if a victim impact statement is being delivered.

Leveson stands by his proposals on remote hearings. He told journalists this week that there is only a ‘finite number of buses to move people between the police station and court, and prisons and court’. With the remand population hovering at 18,000, many defendants are not located in prisons near the court where they will be tried, causing ‘enormous delays’. Remote hearings would also mean fewer police officers waiting in court for hours only to be told they are no longer needed.

Mentions could be remote, he said. ‘When I started as a judge, defendants either decided not to attend the Court of Appeal Criminal Division or if they wanted to attend, they would have to be brought down to London and taken to the Royal Courts of Justice for their 20-minute sentencing appeal. Most decided they did not want to because they did not want to leave their prison cell [as] they might not return to the same prison. Now, almost everyone attends the Court of Appeal Criminal Division remotely, I have heard barristers remotely and I have no problem about that as long as [the hearing] is visible.’

'I do not think the fact the defendant is on a screen rather than in court in those cases to which you refer would make a difference to the majesty or solemnity of the proceedings'

Sir Brian Leveson

On remote sentence hearings, is there a danger that the majesty of the court and how offenders perceive the court could be affected?

‘I do not see why it should,’ Leveson replied. Sentencing hearings have evolved. ‘I remember a judge at the end of a trial saying “stand up, congratulations, double figures, 10 years, take him down”.’

Now, Leveson said, judges provide detailed explanations. ‘How you deal with defendants who refuse to turn up is a really challenging problem. If someone got life for murder, an extra two years will not make much difference… I do not think the fact the defendant is on a screen rather than in court in those cases to which you refer would make a difference to the majesty or solemnity of the proceedings.’

The Bar Council wants the government to turn its attention away from jury trials and focus instead on implementing some of Leveson’s efficiency proposals, such as improved listing practices, better case management and getting defendants delivered to court on time.

However, Leveson told journalists that efficiency alone will not move the dial when it comes to ending the criminal courts crisis. I asked him why not focus on part two first and see how things improve? If the dial does not move far enough, then the government could switch on the legislation curbing jury trials. ‘We have not got the time,’ Leveson replied. He reminded me that the backlog is hovering at 80,000 compared with 39,000 pre-Covid. It is projected to reach 100,000 in November 2027. ‘We have got to throw everything at this problem now,’ he added.

David Lammy says the government is ‘urgently’ considering the proposals set out in part two and will respond to them ‘in the coming weeks’.

How likely is the government to adopt all 135 recommendations? Courts minister Sarah Sackman told MPs this week that her department is already asking local authorities to open up bus lanes to increase the efficiency of prisoner transportation.

Some recommendations will require further exploratory work, such as on the use of AI. But an annual review of legal aid fees? Legal aid lawyers and representative bodies have repeatedly called for this.

As for the recommendation of a new staged legal aid payment system to incentivise earlier engagement and remunerate lawyers – does the Legal Aid Agency, which is only just recovering from a cyber-attack, have the operational bandwidth to introduce this? As the government builds a more resilient system, perhaps now is the perfect time.

2 Readers' comments