Michael Simmons continues reminiscing about life as an (aspiring) solicitor in the 1950s

So there I was – doing two jobs for slightly less than the price of one. The next 18 months flew by.

The quantity of my work was matched by its variety. Obviously, all clients originated with the Major but I was happy that some came back to me for their next job.

Of course, I made mistakes. I assumed that the Treasury Solicitor was a gentleman and agreed terms of reference in an arbitration which meant that my client could not win. Have you stopped beating your dog yet?

In another case, I revealed too much about a client’s affairs to his bank manager, which led to his immediate bankruptcy. I comforted myself with the fact that he was going under anyway.

I felt increasingly like one of that dying breed, the unqualified managing clerk, who had acquired the practical knowledge without the academic qualification. My law degree was of some help but not much.

The Major announced he was going on holiday for two weeks and expected me to do his work as well as my own while he was away. ‘If you’re getting into trouble or need some help, phone my old friend Charlie Ross in Adelphi. We were managing clerks together before the war and he now practises on his own.’

I managed to get by without consulting Mr Ross but it was a near thing. I wouldn’t say I received much gratitude but at least there were no complaints from the Major on his return.

Where litigation was concerned, I did not have time to consult the books and relied shamelessly on counsel. Later I came to dislike the division between solicitors and the bar, feeling that it was not in the client’s best interests. But at that stage it was an absolute godsend.

The time was approaching to think about Finals. The Major made it clear that he was not going to pay me while I was away studying for six months. In fact, he was planning to replace me with a qualified assistant solicitor and a new articled clerk, so I felt quite important.

I learned on the grapevine that local authority grants were available. With some difficulty, I obtained the signature of my father on the form. This was required, even though he had not supported me for many years.

With my finances secured, I had a choice. The College of Law in Lancaster Gate took all non-graduates. Law graduates had the choice of the college or the private tutors Gibson & Weldon who conveniently were situated opposite my office in Chancery Lane. I was told the classes were smaller and the teaching better at G&W, so it was no contest.

I presented myself for the morning lectures on my first day, to be herded into a crowded basement with far too many desks for comfort. If you arrived late, you had to climb over your cursing colleagues to reach your seat.

The lecturers were indeed first-class: all with their individual quirks. This was practical communication at its best and nothing like the tedium of university law lectures. We were supplied with little blue books for each subject and informed that, if we fully mastered the contents, we would have learned enough to pass the exams and qualify.

I had a look at the books and found that they were jammed full of facts. There was going to be an enormous amount to memorise.

I tried to continue to work part-time in the office but soon had to give up.

With a birthday in May, every celebration for years had been spoiled by the need to work for exams. This year was to be no exception but hopefully this was the last exam I would ever have to take. Up to now, I would never claim that I was a serious student but maybe I was maturing. The Solicitors Finals were going to provide me with the tools to practise my trade. In this particular respect, I did not subscribe to the highfalutin view that mine was a noble profession. At best, it was a craft and I needed the academic knowledge to supplement the invaluable practical experience that I had been gaining to make me a complete lawyer. I therefore resolved for the first time in my life to dedicate the next six months to nothing but work.

I had never been one for working alone in my room. I am too easily distracted. I needed a library, preferably where I knew nobody. I was living at the time in Bloomsbury and the London School of Economics seemed ideal. It was surprisingly easy to become a regular with no credentials whatsoever. I always greeted the library staff when I arrived and left.

What I had not reckoned with was the very pleasant postgraduate social life, particularly with the overseas students studying international relations and business. In no time at all I was sucked in, which was probably just as well because I needed the distraction from unremitting work.

The exam was divided into seven three-hour papers over three and a half days. There was then an interval of a week before the five three-hour long honours papers. Stamina was required. Quite a few people who were expected to do well gave up before the honours papers. I was not one of them. I felt like an athlete who had trained for a series of races.

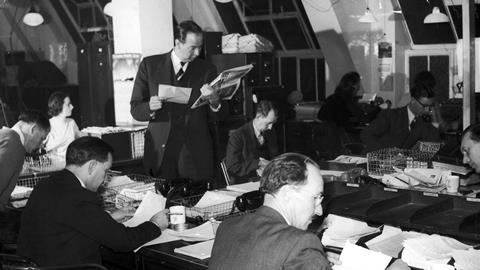

Fortunately, the results were good and I surpassed all expectations, which helped me later in my career. I will always remember the late-night walk to The Times’ offices, then in Printing House Square, and the relief at finding my name in the list of those who had passed the exams.

I was a qualified solicitor!

No comments yet