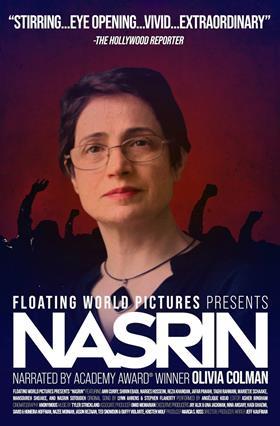

Spoiler alert: Nasrin is not a film with a happy ending. Most Gazette readers will already know that Iranian colleague Nasrin Sotoudeh was sentenced last year to up to 38 years in prison, plus 148 lashes, on charges including 'encouraging corruption and debauchery' after she took on the cases of women arrested for defying the Islamic Republic's dress laws. This secretly filmed portrait sets out what a 57-year-old professional woman has to do in order to merit such a sentence.

The short answer is: be an activist lawyer. For nearly two decades, interrupted by an earlier spell in prison, Sotoudeh has taken on cases which, by any international standard, expose the gross injustices of the Islamic Republic's legal code. We first meet in 2017, hijab worn North Tehran-style, flicked apparently casually over the back of her head, on her way to represent a mother who is powerless to stop her daughter being sexually abused by her former husband. Then she acts for the family of a member of the Baha'i faith murdered by two brothers who did it to in order 'to please God' - and were released after six months.

We aren't told the outcome of these matters, though we can guess. More certain is the fate of client Ali Reza Tajiki: arrested for murder at 15, sentenced to death at 16. Hanged. The phone-captured footage of Tajiki's mother outside Shiraz prison on the morning of his execution is harrowing.

Because of the inevitable political context it is important to stress that Nasrin is not an anti-Iran film. The makers rightly depict the stunning beauty of a large, modern, country - even the dreaded Evin Prison is shot from a photogenic angle. Little cameos - a store selling Santa hats, a performance of Death and the Maiden, an ice-bucket challenge - depict educated, cosmopolitan individuals who are intensely proud of their country and want it to engage with the world on equal terms, not as a troublesome pariah.

Of course this is most eloquently put by Sotoudeh herself, whose family life is really the centre of the film. A Hollywood dramatisation would no doubt include a scene where a family member tries to talk her out of her activism, but there's none of that here. Husband Reza appears as a rock throughout, from his simple opening declaration 'I love Nasrin' to the tremor in his face as he reads out her sentence, deadpan, to camera. As for her children, the furtively-shot footage of Sotoudeh keeping spirits up through the glass at Evin is simply the most moving viewing of the year.

The case to which the film devotes most time is that of Narges Hosseini, one of several women who in 2018 defied the law by removing her hijab in public. We meet her on bail on charges including 'inciting corruption and prostitution, openly committing a sinful act by appearing in public without a hijab and disrupting public order'. Sotoudeh wins her client a 21-month suspension from a three-year sentence.

Eloquently and simply Sotoudeh explains why this cause is worth it. 'If you succeed in forcing us to wear this half metre of cloth, you will be able to do whatever you want with us,' she says. Abolition - as attempted by Reza Shah in the first half of the last century - is not enough. 'Even if they told us today that every woman is free to remove their hijab when they go outside, it would have no value for us. As long as it is in their hands to decide that one day the hijab is compulsory, or one day we can remove it, our decisions will always depend on them.'

At the time of writing, Nasrin Sotoudeh is back with her family, on temporary release for medical treatment after her latest hunger strike. Based on the Iranian penal code's sentencing guidelines, she can expect a recall to serve 12 years in prison and receive 74 lashes.

In these polarised times, discussions of Sotoudeh’s case will inevitably prompt outbreaks of ‘What-aboutery’. It is true that Iran’s is not the only government infuriated by its activist lawyers; it may be arguable that there is a continuum between a home secretary’s disparaging remarks and a sentence of decades in prison. But if such a continuum exists, it is a very, very long one; the tenor of our outrage should reflect that.

Nasrin premieres online at the Global Health Film Festival from 1 to 6 December. The Law Society and International Bar Association Human Rights Institute are hosting an online event on her case from 4:30 pm this Friday. For further information, see here.

1 Reader's comment