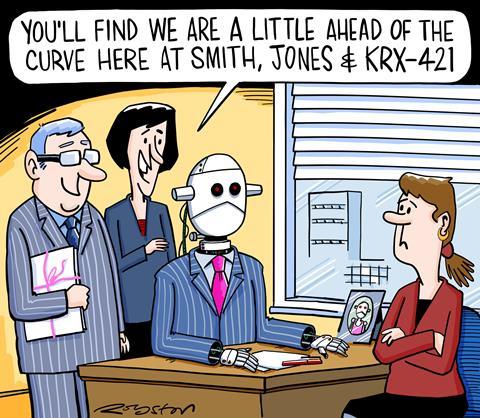

There has been no shortage of doom and gloom about the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on jobs. But law firms of all sizes should take their cue from early adopters who claim the benefits of automating legal work far outweigh the costs and risks.

That said, the statistics do not make for comfortable reading. While less than 5% of jobs can be entirely automated by adapting current technology, about half of all activities people are paid to do in the world’s economy have the potential to be automated by 2055 (or much sooner than that, depending on a variety of factors), according to McKinsey Global Institute. Deloitte forecasts that around 114,000 UK legal jobs are likely to be automated in the next 20 years, ‘most of them junior jobs, with many more at high risk of elimination through technology’.

A study by the Law Society shows that growth in automation and the adoption of AI could lead to 20% fewer jobs in the sector in the next 20 years. But output will rise, too. Society president Joe Egan says: ‘We are seeing the first evidence of how AI and automation will transform the sector. Our research suggests that productivity growth will accelerate to almost twice its current rate by 2038, particularly in large firms.’

Firms can’t bury their heads in the sand, for two reasons. The first is the sheer pace of change in AI, particularly machine-learning technology, whereby computers use a structure called ‘neural nets’ to teach themselves and learn from datasets. According to Ben Allgrove, an IP partner at Baker McKenzie in London, in the past 18 months there has been a ‘perfect storm’ of more powerful computer processing power, better algorithms, big data and money from technology companies. This has led to ‘a huge breakthrough in the ability to use machine learning to produce outcomes and solutions’, both on the consumer side – with the likes of Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant – and on the enterprise side.

Second, law firms risk falling behind and foregoing growth. ‘I don’t buy into the Armageddon scenario, but businesses that don’t change will struggle,’ says Allgrove, who sits on Baker McKenzie’s Innovation Committee and Machine Learning Taskforce. Large firms including the magic circle are investing ‘heavily’ in AI technology; so too elite accountancy firms as they encroach on the legal sector.

What AI can do for you

So how can AI help law firms? So far, it has been applied in two main areas of practice. The first is in e-discovery in litigation, whereby predictive coding (a machine-learning technology) helps to identify relevant documents for disclosure, explains Bruce Braude, head of strategic client technology at Berwin Leighton Paisner (BLP).

A small ‘seed set’ of documents is reviewed by a senior lawyer, which the technology analyses to generate an additional sample for review. BLP, which has an in-house predictive coding resource, asserts that the algorithm identifies relevant documents far more efficiently and in greater volumes than a traditional document review would achieve.

‘Predictive coding is one of the most compelling examples of AI transforming legal service delivery,’ says Nick Pryor, principal knowledge development lawyer and head of litigation and corporate risk client technology at BLP. ‘We secured the first contested order for using predictive coding in 2016, and have used it on a number of matters since.’

‘For disclosure, AI can be utilised to uncover connections between documents, and extract and relate concepts, as well as de-duplicate and cluster at a rate of nearly 2 million documents per hour,’ notes Linklaters banking partner Edward Chan, who is part of a group that leads on the magic circle firm’s initiative on AI. ‘Technology-assisted review can then be leveraged to complete the review of these documents in the most efficient manner.’

The second main area is ‘data extraction’ in contract and other document reviews, typically for due-diligence purposes. BLP has deployed a ‘contract robot’ within its commercial and real estate practices that uses ACE, a technology developed by software company RAVN, which reads, interprets and extracts specific information from documents (such as official title deeds from the Land Registry). BLP is also running pilots in other practice areas, including corporate, finance and projects.

Baker McKenzie has rolled out eBrevia’s machine-learning technology for M&A and other transactional work for its global clients in 11 offices across three continents. The AI software rapidly assesses what information is ‘significant and relevant’ in lengthy contracts, while the algorithm can be adapted to suit lawyers’ specific expertise and practice areas, the firm says.

Allgrove explains that eBrevia’s software and similar products from the likes of Kira, RAVN or Luminance ‘learn’ and can be ‘trained up on different contract clauses’, such as change of control and assignment provisions that could have an impact on a proposed transaction. That is because the software is ‘pre-trained to not only look for the words “change of control”, but to look for the concept of “change of control”,’ he says, adding: ‘The software is evolving all the time, so we are getting better at learning where it is useful.’

‘The application of AI is proving particularly useful in areas that require large volumes of document review such as corporate due diligence situations and real estate land registry reviews,’ notes Linklaters’ Chan. ‘It is also starting to extend out to compliance, where we review large volumes of data against a set standard, and for prediction of litigation where we analyse data against previous judgments.’

Another advance is the emergence of rule-based ‘expert systems’, that try and emulate the reasoning of experts in certain legal disciplines, says Braude. BLP is applying this technology on a ‘small-scale’ in its tax department. He adds: ‘Whereas in the past you would phone a lawyer, and the lawyer would ask a series of questions and say, yes you can or no you can’t, now for certain parts of the law that’s been coded into the [AI] system. It will give you the answer.’

Firms are also building AI and machine learning into workflow systems – or ‘intelligent workflows’ –which also involves AI assessing how to improve processes and performance. Last year BLP’s Manchester office introduced a case management and workflow platform, with ‘enhanced’ AI and data analytics functions, for real estate transactions. The system is best suited for ‘the more process-oriented repeatable parts’ of legal work, Braude notes. It allows clients to interact with it (through personalised portals), for example, by viewing their transactions, initiating new matters, raising requests, and reviewing analytics.

‘We are continually moving additional real estate clients on to this platform and are increasing the number of transaction types that the system can deliver,’ Braude says.

More exciting stuff is coming next – including contract analytics and natural language processing. The first enables firms not only to extract information from contracts but also to flag up risks and other issues. ‘We are seeing a few tech companies offering solutions that can actually analyse that information and say that clause is appropriate or inappropriate,’ Braude says. The second will deliver ‘true semantic understanding of written and spoken legal text’ according to Pryor, and be ‘truly transformative for the legal sector.’

‘Imagine AI tools capable of interpreting legal arguments and proposing counterarguments by reference to procedural or substantive law,’ Pryor says. ‘We have seen some extremely interesting start-up [technology] businesses focused on this area,’ although ‘it’ll be some years yet’ before legally-focused natural-language programming tools achieve the degree of sophistication required for that.

Freedom

What are the main benefits of automation and AI?

‘AI is a lawyer’s best response to the relentless explosion of data across all aspects of society. It allows [them] to efficiently identify and analyse relevant data, and thereby refocus their efforts on the intellectually challenging – and rewarding – aspects of the role that drew them to the profession in the first place,’ Pryor says.

‘The cost savings for our clients are significant, and just as important we trust the technology to deliver quicker, higher-quality results than traditional manual document reviews.’ On the transactional side, the feedback from lawyers at BLP has been equally positive in that it is enhancing job satisfaction. ‘They don’t have to spend time doing these manual data extraction tasks because the technology can now assist them,’ Braude says. There have also been ‘very significant time savings and efficiency gains’.

Baker McKenzie’s main e-discovery platform, primarily used for litigation and compliance investigations, combines software from Relativity and NUIX. It was rolled out last year in almost 50 offices, using the firm’s datacentres in Chicago, Frankfurt, Hong Kong and São Paulo. The firm estimates that innovation initiatives such as the e-discovery platforms and the alternative legal services in Belfast are already bringing in more than $20m in annual revenue.

For Baker McKenzie’s London managing partner, Alex Chadwick, AI tools not only ‘free up significant chunks of lawyer time’, but also ‘deliver value for clients’.

There are other cost savings that can be passed on to clients. ‘A lot of that cost used to go to outside providers,’ including big data hosting companies. ‘We are now doing that ourselves so that we can provide a better end-to-end solution to clients,’ Allgrove says.

For Daniel van Binsbergen, chief executive of Lexoo, investing in tech tools can improve relations with clients as in-house legal teams are getting ‘increasingly fed up with very large bills for junior associate time spent on jobs that could be done by tech.

‘There’s a huge benefit to firms to show their clients they are investing in becoming more efficient and passing those savings on to them,’ he adds.

The bugbear is machines replacing humans, but firms contacted by the Gazette say AI has not meant job losses so far. ‘We believe technology is only a vehicle to deliver relevant, curated content and outstanding legal expertise, which is where our lawyers provide the most value to our clients,’ Benamram says.

Predictive coding has meant a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way disclosure work is undertaken, Pryor observes. ‘You really do need fewer people to get [more]work done because it is assisted by machine-learning technology. So in that sense you can see how the need for a large body of paralegals might go down if that is how traditionally you would source that work.’ But he adds: ‘We have not seen anything about the actual capabilities of these systems that undermines or reduces the requirements for genuinely skilled lawyering. What it does do is empower those lawyers to understand and grapple with data, and to do more routine tasks much more efficiently.’

In future, the ‘legal pyramid’, with a handful of senior partners at the top and ‘an army of junior lawyers doing repetitive search and verification work at the bottom, will be replaced by a leaner workforce,’ according to Deloitte. Firms will search a smaller talent pool to find their most senior staff, and will draw talent from a wider range of disciplines including technology development and data analysis.

Pryor points out that not a single job has yet to go in his firm, and is sanguine about the ‘reshaping’ of law firms as they ‘build around these technologies and find out how they can deploy them’. For example there will be more ‘multi-disciplinary’ teams and ‘an awful lot of new and much more interesting job titles and roles coming up’, he says, pointing to his and Braude’s jobs.

Firms are recruiting data scientists and analysts, forensic technologists, legal engineers and data visualisation consultants. ‘Those are things that even 12 months ago no law firm was doing,’ says Allgrove.

There are other reasons why lawyers should embrace automation without fear. ‘We are still a long way from an all-seeing replacement for a human lawyer because that really requires general AI, and all the applications at the moment are narrow AI and specific to a particular function,’ Allgrove says. ‘Narrow AI’ is the only form of AI that has been attained so far, while general AI, which is capable of understanding its environment as humans would, has been elusive.

Partnerships

Since the start of 2013 through to Q3 2017, investors have deployed $918m across 304 legal tech deals, according to research firm CB Insights. But it is worth noting that automation technologies do not come fully-formed, and require significant legal input, hence the need for firms to work with the tech vendors.

For the more sophisticated and advanced software (such as eBrevia, Luminance or RAVN) firms rely on enterprise software licensing, but they still need to work with vendors to adapt the rapidly evolving technology. Firms are also ‘partnering’ with providers, particularly with small tech players.

‘It’s recognising that law firms have a huge amount of value to bring to the table in terms of data, domain expertise, client relationships and understanding client needs,’ Allgrove says.

‘There is a very open field as to how you price [automation technology] into the business and how you define the value proposition,’ says Pryor. ‘It is not as simple as looking at the way you might traditionally finance and invest in IT technologies that are the core part of keeping the business afloat.

Braude concurs, saying: ‘It could either be a loose partnership in the sense of evaluating their technology, piloting it on various applications, and giving them feedback as to how they can enhance their own platform, or there could be more structured partnerships where we will work with a provider and say “drive me to that client”.’

Linklaters, which uses AI most prominently in its finance practices, has developed Nakhoda, a ‘proprietary’ AI, in conjunction with London tech startup Eigen Technologies.

‘It is a dynamic platform that provides rapid legal analysis and document characterisation. It brings together in-depth legal expertise, machine-learning algorithms and natural language analysis to build bespoke solutions for our practices and clients,’ Chan says. For example, it is used for comparing documents such as non-disclosure agreements. But the firm also uses a number of external technology providers, such as KIRA and RAVN, ‘which are also helping to transform the way we read, categorise and extract large amounts of information. These solutions require limited legal input and customisation to develop functionality,’ Chan says.

Dentons has established wholly owned legal technology accelerator Nextlaw Labs, which invests in, develops and deploys new technologies to ‘transform the practice of law’. It has invested in several technology startups including ROSS Intelligence, which has developed an IBM Watson-powered cognitive computing to refine expert legal research; and Beagle, a startup that is using AI to automate legal contract review.

The global firm is also working with a number of other tech start ups to pilot AI tools. In 2016, the Paris office started a ‘co-innovation partnership’ with Predictice, an AI-powered platform leveraging predictive analytics, Marie Bernard, CEO of NextLaw Labs and Europe Innovation director at Dentons, says. ‘Looking at the track record of previous similar, litigation, it delivers an estimate of benefits, as well as a map of the most favourable jurisdictions depending on the type of problem. The tool could eventually help lawyers adjust pricing according to these statistics,’ she says.

Dentons’ Amsterdam office started testing the Clocktimizer in December. This provides insights about profitability and pricing based on time-card narratives, and helps keep track of time and budget, while Dentons’ corporate practice in London is starting a pilot with Luminance and its AI due diligence application.

Investments in automation technologies are big – ‘there are a lot of zeros’ Allgrove says – but that does not mean they are out of the reach of smaller firms. A lot of these systems are cloud based or are hosted solutions, not big platforms that have to be implemented within a law firm,’ says Braude. ‘While there’s a constant investment in terms of people, and evaluating and using the systems, they are becoming in my view more affordable.’

There are, for example, cloud-based pay-per-use options where the amount that firms pay depends on the volume of documents that are fed into the system. Firms of all sizes will soon be jumping on this rapidly accelerating bandwagon.

Top tips

- Try to introduce the technology in collaboration with a client

- Clients are increasingly willing to collaborate on new initiatives with their legal providers, and having a client involved ensures that the initiative gets the right focus and prioritisation in the firm (Bruce Braude)

- Don’t wait for a perfect and 100%-accurate solution before adopting

- Start experimenting (with checks and quality controls) with technology partners. Some of these technologies are cloud-based and don’t require significant upfront cost commitment (Bruce Braude)

- Don’t underestimate the investment you will need to make

- Successfully deploying AI-enabled systems requires material non-cash investment in time, process mapping and alignment, data cleansing and training. Understand this upfront (Ben Allgrove)

- Identify the problem you are trying to solve

- There are lots of AI solutions in the market looking for a

- problem. Effective deployment depends on making sure you understand the problem that you are trying to solve (Ben Allgrove)

- Be prepared to fail

- Technology is rapidly evolving. You need to be prepared to try things and iterate when they do not work or [until] a better way of doing things emerges (Ben Allgrove)

Using AI to find the right lawyer

London-based legal tech start-up Lexoo, launched in June 2014 by ex-City lawyer Daniel van Binsbergen, is a digital marketplace for legal services which operates a ‘curated’ network of over 650 boutique lawyers in over 35 different countries.

Lexoo matches UK small and medium-sized enterprises and entrepreneurs with former ‘big-law’ lawyers, now working independently or in boutique firms on a lower overhead basis.

‘Lexoo has built an AI/machine learning algorithm which crunches data to decide which lawyers are most relevant to a job, as the platform will only invite the most relevant four to quote,’ van Binsbergen says.

This looks at large amounts of historic performance data, including average reviews for similar work by other clients, response times and how often a lawyer would be hired by a client after an initial phone call, explains van Binsbergen.

‘The beauty is that with every increasing bit of data we collect on our lawyers, the algorithm becomes stronger.

‘The take-up has been huge. We’ve had more than 23,000 businesses submit jobs on our platform since our launch four years ago. By pinpointing the right low-overhead lawyers, clients typically save around 45% compared to what specialists with equivalent expertise charge at larger firms,’ says Binsbergen.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet