The way that AI-native law firms handle legal tasks and processes points to an evolution of ‘outcomes as a service’

The emergence of AI-first and AI-native law firms feels like a reworking of the original tech-powered legal platforms. These started to blur the boundaries between legal and legal tech offerings over a decade ago. But while firms have long been spinning out tech start-ups, products and consultancies, with mixed success rates, this time it is the other way round. Tech companies are launching affiliated legal services and are competing with law firms as regulated entities. Last year saw the first legal tech company acquire a regulated law firm when LawHive acquired Woodstock Legal Services, and Garfield Law became the UK’s first SRA-regulated AI-native law firm.

Last week, Financial News reported that agentic AI legal platform Harvey is looking to recruit top legal talent, offering bumper pay packages that include equity and spending money for sabbaticals. (Agentic AI refers to systems that can autonomously make decisions with limited supervision.) This drew speculation that Harvey might be planning to introduce legal services too, which CEO and co-founder Winston Weinberg denied unequivocally in a LinkedIn post.

He highlighted several key strategic reasons, including: ‘We have a bigger total addressable market by helping every law firm and in-house team globally become AI-first than to create a single AI-first law firm.’ While this makes business sense for Harvey – which is expanding its European operations and has announced plans to open an office in Paris and a new head of EMEA sales – the latest AI-native firms are competing with incumbents in specific practice areas.

AI natives

AI-native firms are built on proprietary technology rather than relying on a legal-specific agentic AI platform such as Harvey or Legora, or generalist large language models like OpenAI’s GPT models or Anthropic’s Claude. They tend to be designed to handle specific types of legal work quickly and cost-effectively by combining tailored AI workflows with lawyer review/approval.

Last November, New York legal tech start-up Norm Ai launched Norm Law LLP, an AI-native law firm. Norm Ai is a legal and compliance platform for major financial institutions, with a client base representing $30tn in assets under management. Founder and CEO John Nay, a serial entrepreneur, explains that Norm Law is a separate entity from the Norm Ai platform, created to meet the needs of Norm Ai’s clients. ‘What we had already done using AI and legal engineering to turn legal workflows into AI agents resonated with Norm Ai clients in large financial institutions, so we asked them what would be most helpful to them in terms of an AI-native outside counsel.’

Norm Ai raised $50m in Series C funding from asset manager Blackstone (which was one of the company’s original investors and deploys Norm Ai within its legal and compliance group) to launch Norm Law. This combines a legal workflow automation platform with supervision by expert attorneys.

While Norm Law has only been established for a couple of months, Norm Ai, launched in 2023, employs over 150 people. These include AI engineers and software engineers who built a modular platform where the modules represent the building blocks of legal workflows. Legal engineers work with lawyers, combining different modules to create agentic workflows tailored to different types of legal work. Lawyers have the final responsibility for the legal advice provided.

Last week, Norm Ai introduced an agentic solution for due diligence questionnaires and requests for proposal completion. This generates questionnaire responses directly from a firm’s pre-approved materials. AI agents interpret the questions and pull the most relevant answers from a pre-approved answer bank, or draft new responses using approved data. Once completed, questionnaires are exported back to their original format for review and approval before submission.

Crowded airspace

In 2016 US journalist Kyle Chayka coined the term AirSpace to describe the formulaic Silicon Valley-influenced design style that was starting to take over the world. He observed that the most popular Airbnb rentals in multiple locations had similar aesthetics, and hipster coffee shops were ‘marked by an easily recognisable mix of symbols – like reclaimed wood, Edison bulbs, and refurbished industrial lighting’. Ten years on, wherever you are in the world, you can stay in interchangeably similar apartments and get the same lunch. Apart from a few game-changers, legal AI is in danger of following a similar direction. LegalTechnologyHub’s latest LTH GenAI LegalTech Map features 855 products, and shows that the number of GenAI legal products has more than doubled since February 2025. As law firms transition from AI adoption to AI-first, there will be fewer opportunities and probably less investment – with so many lawtech start-ups flying in the same AirSpace.

Outcomes as a service

Garfield is the UK’s first SRA-regulated AI-native firm built on a proprietary AI model. Its CEO and co-founder, former litigator Philip Young, realised that unpaid invoices were a pain point for businesses across the entire economy and that GenAI had the potential to manage the small claims process.

Young and his co-founder, quantum physicist Daniel Long, built a GenAI platform that replicates what a law firm would do to help a client get paid. Garfield reads invoices and contracts, checks the validity of claims, and generates pre-action letters and documents for claim filings at the Small Claims Court. Having undergone the lengthy process of becoming SRA-regulated in 2025, Garfield handles cases directly for claimants and is available to law firms as a white-label product.

But are Garfield and other AI-native firms a new business model because GenAI handles most legal tasks and processes, or is this simply the next stage in legal’s digital transformation? Young believes it is an evolution to ‘outcomes as a service’. He continues: ‘Because of the way lawyers are trained, we tend to think of process rather than outcomes, whereas what clients want are outcomes. Clients who have unpaid invoices simply want to get paid. Whereas this was traditionally a human process, now we use technology to achieve the same outcome. The fundamental difference is that a traditional firm would probably assign a small debt claim to the most junior member of the team. Garfield is essentially providing a technological alternative to a paralegal, trainee or newly qualified solicitor.’

However, it is not entirely an alternative to lawyers, because Young checks all documents before they are submitted. ‘This is partly driven by the regulatory rules,’ he says. ‘We have built an internal system called auto-check that also checks documents that fall outside the regulations, such as pre-action correspondence. It’s 99% correct and eventually it will take over checking those documents and only escalate things that it is unsure about. We will end up with multiple levels of checking, as technology, when you build it right, can be more accurate and consistent than humans, so the idea is to end up with a superhuman level of performance.’

Like Norm Ai, Garfield is a modular platform. Young and his team are working on new offerings in response to users’ requests and suggestions. ‘One of our ambitions is to move beyond being a one-product company into a platform providing a series of access to justice products. The great thing about civil procedure in the courts is that it is largely the same across many different types of case, and if [a GenAI product] can handle particular stages of a certain type of case, you can often apply what you’ve built to other categories.’

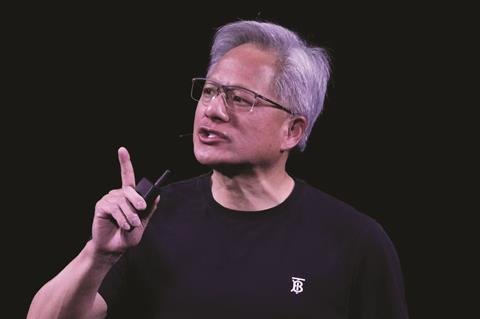

'What’s the purpose of the lawyer versus the task of the lawyer? Reading a contract, writing a contract is not the purpose of the lawyer. The purpose of the lawyer is to help you resolve conflict… to protect you'

Jensen Huang, Nvidia

AI in the frame

The concept of agentic AI as an evolution of service delivery rather than a new business model reflects Nvidia chief Jensen Huang’s view that rather than replacing human roles, agentic AI enables humans to become more productive by integrating into organisations’ task-purpose framework. Speaking on the No Priors podcast on 8 January, he referred directly to the legal sector. ‘It’s very easy to draw a straight line of extrapolation from… [AI] tools that help lawyers be more productive, [to] it’s going to replace the lawyers.’

He continued: ‘What’s the purpose of the lawyer versus the task of the lawyer? Reading a contract, writing a contract is not the purpose of the lawyer. The purpose of the lawyer is to help you resolve conflict… to protect you. So, it’s really important to go back to what is the purpose of the job, versus the task we use to perform that job that changes over time.’

Values and valuations

There is plenty of commentary around the very high valuations of legal AI companies. On 30 December, Meta announced the acquisition of Manus, a Chinese-founded, Singapore-based start-up that has developed general purpose, multi-agent architecture. While Manus was valued at $2bn prior to the acquisition, as legal tech analyst Raymond Blyd of Legalcomplex observes, this is a quarter of Harvey’s $8bn valuation following its latest investment round.

The competitive environment around legal AI is increasingly crowded and complex. Blyd’s financial analysis highlights gaps between analyst valuation and market value, and some missing numbers. ‘Valuations matter to investors and value matters to lawyers, but does value for lawyers add up to valuations thus return on investments for investors?’ he asks. ‘While valuations are vague indicators, actual exit values are a more tangible measure of value. Unfortunately, only 10% of acquisition announcements shared prices.’

AI-native law firms have been described as new business models. However, they all use human lawyers to review and approve the outputs of agentic AI processes. As AI adoption across legal services increases convergence between traditional firms and frontier AI natives, this trend could well challenge the legal AI start-up boom when – at least to some extent – the moniker ‘AI-first’ applies to every firm.

No comments yet