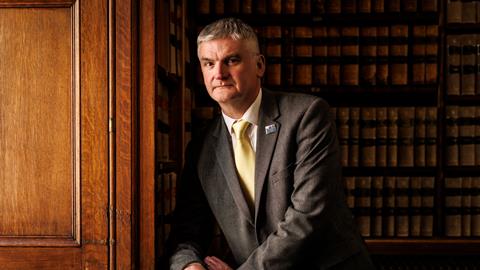

Mark Evans brings a distinctively Welsh and working-class can-do attitude to the Law Society presidency, writes Paul Rogerson. He’s a world record-holder too

BIOG

BORN

St Asaph, north Wales

EDUCATION

Holywell High School (1982-1989)

LLB, Leicester Polytechnic (1992)

College of Law, Chester (1993)

Admitted as a solicitor (1995)

ROLES

Trainee, salaried partner, equity partner, director/shareholder, consultant

Allington Hughes Solicitors/Allington Hughes Ltd (1993-2022)

Tutor, University of Law (Manchester, Liverpool and Chester) (2021-)

Council member for Cheshire & North Wales, Law Society of England and Wales (2015-2025)

Chair, Law Society Wales Committee (2017-2021)

Council member for North Wales, Law Society National Board for Wales/Bwrdd Cenedlaethol Cymru (2022-)

Deputy vice president, vice president, Law Society (2023-2025)

KNOWN FOR

President, Law Society (2025-2026)

'Wales is strange because we don’t really have a class system. My mother would say to me, "you can talk to anyone. It doesn’t matter what rank you are at"'

Mark Evans is a solicitor moulded by the values he grew up with.

Welsh values, he tells me. Working-class solidarity and community – but also autodidacticism and aspiration.

Volunteering, too. Nearly one in three people over 16 formally volunteers in Wales. In England, the proportion is half that.

Evans might be their archetype. School governorships and running the local scout group have counted among his many extra-mural activities. That is in addition to the multiple, time-consuming roles he has undertaken on the Law Society’s Council, board and committees.

It runs in the family. The Law Society’s new president is the son of an orphaned steelworker who lived in a children’s home until he was adopted at the age of 12. But Mark Evans’ father became a pillar of the community too; chairing a school’s board of governors, just as his son went on to do.

‘It’s kind of hereditary in Wales,’ says Evans. ‘My father always took the view that education was the route to improving yourself. He never complained about his background. He always said, “you can do better”. Wales is strange because we don’t really have a class system. So my mother too would say to me, “you can talk to anyone. It doesn’t matter what rank or what level you are at”.’

So it was that Evans’ two brothers, both older, were the first in the family to go to university. State-educated Mark ranks among the 18% of lawyers who come from lower socio-economic backgrounds, according to SRA diversity statistics. He would therefore have qualified for the Law Society’s Diversity Access Scheme, had he needed it.

Money was always limited, but Evans’ parents broadened his horizons when the opportunity arose. He recalls coach holidays to the continent, embarked upon as a teenager because they were more affordable than flying. People used to get the bus to the Costa Brava back then, as I can attest myself.

‘This was a time when my parents discovered “going abroad” for the first time,’ he smiles. ‘Austria, Germany. Because there were three of us, I always had to sit next to someone else and so I’d talk to them. It all sort of opened up your eyes to the world.’

In his teens, Evans wanted to join the police force. He only ‘fell in to the law’ when a history teacher at school secured a week’s work experience for him at a Denbigh practice. ‘I just fell in love with it,’ he recalls.

A 30-year career followed at the cross-border high street general practice Allington Hughes. Evans progressed from trainee to equity partner and then consultant, before leaving three years ago for academia and a lectureship at the University of Law.

Running the show

Chancery Lane has not had many working-class presidents, but Mark Evans may well be in a minority of one when it comes to Guinness World Records. In 2020, as part of the Alzheimer’s Society team, he was one of 37,966 people who completed a remote marathon in 24 hours as part of the Virgin Money London Marathon (UK). The event was staged after the London Marathon was postponed due to Covid-19.

That 26.2-mile journey was intensely personal. ‘In 2014 my mum died and my dad went into a care home,’ he explains. ‘Over the next six years, dad’s health steadily got worse. I put on a lot of weight and really became kind of lethargic. So, in 2019 I went to my wife’s gym and signed up to do “couch to marathon” in 10 months – a “Chester Triple” it’s called [10K, half marathon, marathon].’ Evans lost two and a half stone and has since founded the fast-growing LegalRunner network. ‘It’s very therapeutic, because you can offload to whoever you are running with. They’ll understand what it is to be a solicitor. Men in particular open up when they’re running, because you’re side by side and it’s a closed space. There’s no eye contact!’

A born networker anyway, Evans was never going to find it difficult to empathise with provincial solicitors struggling with the vicissitudes of contemporary practice. In his time at Allington Hughes, he was variously chair, management executive, business development partner (‘new areas of work, succession planning and growth’), personnel partner and COLP/COFA.

‘I can bear witness to the struggles of high street solicitors,’ he says. ‘For example, my firm had 11 or 12 duty solicitors [crime], but we lost people to the Crown Prosecution Service. And generally speaking, recruitment and retention are difficult if you’re in a rural location or small town. The attraction of moving on to a big city for a better salary is always there.’

And so we return to community – ‘you draw strength from it, don’t you?’ – which will be one of the themes of the Evans presidency. Nothing is more commendable to him than practising in (and giving back to) the place that made you.

‘Obviously, everyone has a choice about what they want to practise and where,’ he adds. ‘It has given me great joy that l came to live and practise in north Wales. Being close to home, being part of the community, has been beneficial to me and has given me things I would not have had if I’d moved away.’

One bugbear of Evans is the absence of level 7 apprenticeships in Wales, which uproots aspiring lawyers who might otherwise have developed their talents locally. ‘In my home town we’ve lost two 18-year-olds who’ve gone to do apprenticeships in London law firms. We continue to lobby the Welsh government to correct this anomaly,’ he says.

Evans met his wife, a sheep farmer’s daughter from west Wales, in 1996. This, too, shaped his career. ‘For the last 30 years, I’ve spent most of my holidays at a farm: shearing, fencing, generally helping out. [Allington Hughes was] a National Farmers Union panel firm for north and mid-Wales. Most of my clients were farmers, but I could relate to them. I had some knowledge of their world.

‘If people think you are similar to them, they open up to you and they trust you. And you build connections. You get generational work – grandfather, father, daughter. And this was before the internet and mobile phones. We didn’t have a computer. It was about personal relationships.’

The onset of law’s very own ‘machine age’ has since atomised legal lives, which worries Evans. He mentions one solicitor of his acquaintance who works remotely from a one-bedroom London flat. She just ‘moves her chair around from the kitchen to the bedroom’, he says. ‘I asked her, “do you not go out?” “When do you actually turn the computer off and have a break?” She doesn’t. She’s on an incredibly good salary, but is that a life? I don’t know.’

'Solicitors shouldn’t be answering emails out of hours. Individuals need to look after their own health and wellbeing, but we need to look at what law firms can do to assist'

Which brings us to another presidential theme related to community – mental health and wellbeing. Evans’ timing is adroit, since this interview is being published on World Mental Health Day.

‘Speed of communication has impacted the legal profession profoundly,’ he reflects. ‘Whereas once you could leave the office on Friday and wait for the post to be opened on a Monday morning, now you’re bombarded. You’re accessible 24/7 by emails and messages.

‘While we can adapt and use technology, we’ve also got to have some guidance or framework on what is “the norm”. People’s expectations need to be managed. Solicitors shouldn’t be answering emails out of hours. Individuals need to look after their own health and wellbeing, but we need to look at what law firms can do to assist.’

He adds: ‘My gut feeling is we need to be thinking about what we can do to change our working environment. Even I never took more than a week’s holiday. We had to ask permission for more than two weeks. These days, two weeks isn’t enough. Firms need to be thinking about offering unpaid leave, or career breaks, or whatever they need to – because people need to recharge. If they’re constantly on a treadmill, people are either going to leave the profession or encounter problems with their mental health.’

It would seem to be indisputable that the profession has a serious problem here. A survey published last week by mental health charity LawCare found that two-thirds of legal services workers want to quit the sector in the next five years. More than three-quarters (79%) of respondents reported that they regularly work over their contracted time, while 8.5% estimated they work at least 21 hours’ overtime every week. Half said they had experienced anxiety often or all the time in the past year. Evans is attending the LawCare report’s formal launch next week, at which a panel discussion will be held on where the profession goes from here.

Young solicitors in particular are vulnerable – they do not get their twenties and thirties back when the burdens of the office ease.

‘At the junior lawyers summit last year, I was asked what advice I’d give looking back on my own life. My answer was, “don’t stop doing the things you enjoy”. We get into our twenties and our career takes over, and our family perhaps takes over. If I could have changed anything, maybe I should have carried on doing some of those things.’

Like all Chancery Lane presidents, Evans also gets to enjoy 12 months in the political spotlight as the Society’s public face. Not easy, when problematic policies ranging from junking jury trials to leaving the European Convention on Human Rights have landed squarely in the mainstream. As the flags flutter from a lamppost near you, Westminster is turning feral. Even a Labour home secretary and former lord chancellor wants to slap further proscriptions on octogenarians waving placards.

'Solicitors provide a community service that is just as important as the health or education services'

How does Evans plan to get past the tired and time-dishonoured ‘fat cat’ and ‘ambulance-chaser’ stereotypes, to make sure the profession gets a fair hearing?

‘An area of major importance to me is the impact of the legal sector on the economy,’ he replies.

A good point. The Law Society calculated in March that the legal sector has a combined direct and indirect contribution to the economy worth £74.4bn and exported £9.5bn in 2023. But Evans takes a less Olympian view, reverting once again to the ‘C’ word.

‘The local legal sector is integral to and supports the local community,’ he stresses. ‘We are on virtually every high street in every town in England and Wales. Contrast that with most banks and building societies, which have left. What I will say to politicians is that solicitors provide a community service that is just as important as the health or education services. At a Friday constituency, what are the issues that confront MPs? They’re legal issues. Problems with housing, or the local authority, for example.’

He concludes: ‘The vast majority of solicitors are doing incredible work, day in and day out, over a wide variety of transactions. Yet they get very little credit or gratitude for it.

‘If they [politicians] can be positive about the important role we play in communities and in society, then maybe we can change the narrative around how solicitors are portrayed by the press and subsequently viewed by the public.’

No comments yet