There was a nasty shock in store for claimant lawyers and funders involved in competition collective actions last month. Sleepy August was rudely interrupted by an unexpected announcement from the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) that it has kicked off a review of the collective actions regime, with an open call for evidence that closes on 14 October.

In explaining the reasons for its review, the DBT was careful to acknowledge the need for consumers to be able to achieve redress where they are harmed by anti-competitive behaviour. But reading between the lines, the impetus for this review has surely come from the business lobby, which has managed to convince the government that the current collective actions regime is harming business and threatening the holy grail of economic growth.

The DBT’s call for evidence makes several references to the ‘burden on business’, and the need to ensure that this is not disproportionate. In justifying the need for a review, it highlights the gulf between the present caseload and what had been originally anticipated. The impact assessment undertaken before the regime came into being in 2015 had estimated its total cost to business at an annual £30.8m. However, the DBT points out that in fact, tens of billions of pounds have been claimed in damages under the regime, with hundreds of millions spent on legal fees.

It is not only the size of cases that concerns the government, but also their nature. It had been envisaged that most cases before the Competition Appeal Tribunal would be ‘follow-on’ actions in which the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) or European Commission had already investigated anti-competitive behaviour and made an adverse finding. In fact, the DBT states, some 90% of the CAT’s current caseload is standalone cases. Why does this matter? The concern seems to be that the regime has gone well beyond cases in which a regulator has already found wrongdoing, with businesses instead facing a far broader exposure to large-scale lawsuits and what business lobbyists term predatory litigation.

Read more by Rachel Rothwell

There is no doubt that collective actions pose a significant threat to any business that breaches competition law, or sails close enough to the wind in that regard. The financial consequences of being on the receiving end of one of these class actions can be astronomical. Meanwhile, the potential amount of compensation for each individual class member can seem tiny compared with the possible payouts for lawyers and funders. It is worth remembering, however, that funding arrangements must be approved by the CAT; and as demonstrated in May’s Merricks v Mastercard settlement, the tribunal is prepared to slash a funder’s return if it so wishes. The funder in Merricks is now bringing a judicial review of the CAT’s decision on how the £200m settlement should be distributed.

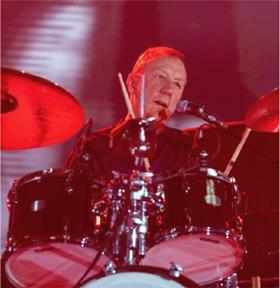

Meanwhile, in a new CAT decision this month, the tribunal refused to certify a proposed claim by solicitor and Blur drummer Dave Rowntree (pictured) on behalf of songwriters, concerning the distribution of royalties. While not part of its main reasoning, the CAT commented: ‘We are alert to the fact that where preparation of class actions are initiated by lawyers, rather than members of the class – as in this case – it may be that it is the revenue stream to the lawyers and the funder which is the principal incentive to the pursuit of these proceedings rather than the benefits to the class.’

So the signs are that the CAT is ready and willing to take an active role in monitoring the cost of collective actions and ensuring a proportionate relationship between the cost of claims and the financial benefit to individual class members. But it may be too late. The pro-business tone of the DBT’s announcement suggests that the collective actions regime will be significantly curtailed. In its place, in keeping with the direction of travel we are already seeing from the judiciary, will be a predictable push towards the far cheaper option of voluntary redress schemes and alternative dispute resolution.

Claimant lawyers will protest that the collective actions regime is still in its infancy and it is too soon for change. They will argue that while it has technically been in place for 10 years, it did not really get going until the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in December 2020, which clarified that a low threshold applied for certification of proceedings. What is more, these cases take a long time to progress, and defendants have been astute at challenging every aspect of the new rules. These are solid points, but my guess is that claimant lawyers will find themselves shouting into the wind. Reform is coming, and the collective actions regime is about to have its wings considerably clipped.

Rachel Rothwell is editor of Gazette sister magazine Litigation Funding, the essential guide to finance and costs.

For subscription details, tel: 020 8049 3890, or go to Litigation Funding

No comments yet