Government claims that outsourced criminal justice services are working well are routinely greeted with scepticism by frontline lawyers. Eduardo Reyes investigates

The low down

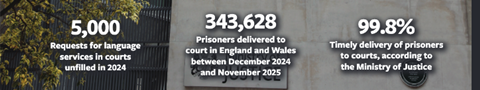

The Ministry of Justice claims staggeringly high performance levels for key outsourced services upon which the conduct of criminal trials depends. Timely delivery of prisoners to courts is apparently achieved 99.8% of the time. Only 0.7% of ineffective trials are delayed due to the lack of an interpreter. Court interpreters surveyed are happy with their lot. So why does the Bar Council’s new chair single out prisoner escort service problems as ‘the whine that became a roar’? In truth, it is easy to find routine examples of late transport delaying trials, adding to the backlog. And ‘satisfied’ interpreters have been striking over pay and unreasonable work demands. The scale of these outsourcing problems has the potential to undermine the government’s criminal justice reforms.

The scene: a juvenile murder trial at the Central Criminal Court last year, a little after 2pm. The judge enters the court and we all rise, only for the judge to wave us back down to our seats. He has appeared only to apologise for a delayed start. The prisoners, he says, cannot be brought up yet, because staff from the outsourcer company responsible for escorting them have not yet had a full hour for lunch. The morning over-run, he adds for good measure, was caused by these same prisoners’ late delivery to court that morning by the same provider. The judge names the outsourcing company responsible for the service and leaves.

As an observer, I feel a point is being read on to the record by a jurist who is clearly irritated by the scenario. And so we all sit and wait – defence and prosecution barristers, defence solicitors, Crown Prosecution Service lawyers, technicians and other court staff. Ranks of passive, unoccupied – and expensive – professionals.

When prisoners are not delivered on time, the delay leaves many, many people waiting and uses up precious court time. With the criminal justice system universally acknowledged to be in crisis, is there something about this outsourcing arrangement that is adding to the system’s failures?

Denial

Not according to Serco, one of two companies that holds a contract for prisoner escort, and not according to the Ministry of Justice, which awarded the contracts in 2019. The Prisoner Escort and Custody Service (PECS) contracts boast exemplary performance, both tell the Gazette.

‘Serco delivers over 99.8% of prisoners to court on time,’ the company’s spokesperson says. ‘Delays are rare and are caused by multiple factors, the majority of which are outside of our control, including traffic incidents or lengthy wait times at prisons and police stations for prisoners to be handed over.’

The company also draws attention to the terms of the contract under which it should be held to account. Fines of up to £625 can be levied for every 15-minute delay in the delivery of prisoners to court.

A spokesperson for the second company, GEOAmey, replies in a similar vein. The company has been delivering services under the PECS contract since 2011, and since August 2020 has been responsible for the north of England, the Midlands and Wales.

‘Our contracted performance for delivering people to court on time was 99.7% in 2025. There were only 49 instances where we failed to provide a dock officer out of 187,238 individuals presented to court in our contracted area,’ the spokesperson says. ‘The process of escorting and delivering those in custody to court is highly complex and has multiple dependencies, some of which are outside of our control, not least the ongoing prison population pressures. We are very proud of our role in supporting the court service by delivering those that are required in court, safely, securely and in the overwhelming majority of cases, on time.’

Serco and GEOAmey have the full confidence of the Ministry of Justice. An MoJ spokesperson responded to the Gazette’s questions on Serco and GEOAmey thus: ‘We recognise that delays can arise for a range of reasons across the justice system, and even short disruptions can have an impact – but prisoner transfer delays are not driving significant delays in the Crown court. Prisoner escort contractors deliver over 99.8% of prisoners to court on time and face significant financial penalties when they fail.’ Asked what fines have been levied on Serco and GEOAmey for delays, the MoJ stated that this is commercially sensitive information.

The Gazette also asked the MoJ about the impact of delays due to the unavailability of interpreters – another vital service that has been outsourced to a private provider. ‘More than 99% of trials needing interpreters go ahead as scheduled,’ it said.

Sir Brian Leveson will deliver

The conviction that problems in the criminal justice system lie elsewhere underpins justice secretary David Lammy’s view that Sir Brian Leveson – and not frontline trial participants such as solicitors, barristers and interpreters – will provide the answers to the crisis in the criminal justice system.

First, that is to be achieved through Leveson’s proposals to limit jury trials, though these have run into trouble at Westminster.

Second, there will be a set of recommendations made in part two of Leveson’s review, yet to be completed.

‘Alongside our major reforms,’ the MoJ spokesperson adds, ‘we are also investing £450m per year more into our courts.’

99%

The staggeringly high success rates achieved by Serco, GEOAmey and the MoJ are dutifully and transparently reported. The PECS suppliers’ contractual performance indicator for prisoners delivered to court when a delay is the responsibility of the supplier is 99.2% – 99.8% at Serco, which covers southern England; with GEOAmey on 99.7%.

According to published key performance indicators for government’s most important contracts, of the 343,628 prisoners delivered to court between December 2024 and November 2025, there were 273 contracted failures.

At a time when so many public sector functions are routinely pronounced ‘broken’, it should be a welcome break to celebrate services that work. A pleasant change, perhaps, for hard-pressed professionals to find an interface with state-linked legal services that operate properly. Look past the wreckage of the Legal Aid Agency’s superintendence of its responsibilities and you can see the glittering examples of prisoner escort delivery services; beyond that, perhaps caught by a shaft of sunlight, punctual, word-perfect translators.

Yet plaudits are rare. In reality, complaints from frontline practitioners are common, and their expectations of these high-scoring outsourced services are low. Indeed, it is very easy to find examples of consequent delays to trials, which are described as commonplace.

The Gazette contacted criminal defence solicitors across England and Wales, asking about their experience of court delays attributable to prisoner transport in the magistrates’ and Crown courts. For experiences of the interpreter contracts, held by companies thebigword and Clarion UK Ltd, we draw on the House of Lords’ Public Services Committee’s work, relevant professionals (including unions who directly relate the experience of MoJ staff) and the department’s official responses to our questions.

Language barrier: ministers and interpreters

‘More than 99% of trials needing interpreters go ahead as scheduled,’ says the Ministry of Justice in response to the Gazette’s questions about the delivery of interpreting services in criminal trials. Two companies hold the contract for these outsourced services: thebigword and Clarion UK Ltd. An MoJ spokesperson adds: ‘The majority of interpreters were satisfied or very satisfied with their experience of interpreting assignments for the MoJ.’

That picture is fiercely contested. In 2024, the House of Lords Public Services Committee gathered evidence on the standard of interpreting services provided through these outsourcing contracts. Its findings were published in March 2025.

The committee concluded that the current state of interpreting services in the courts is inefficient and ineffective, and poses a threat to the administration of justice.

Peers identified ‘a clear disconnect between what the government thinks is happening, what the companies contracted to deliver the services believe is happening, and what frontline interpreters and legal professionals report is happening with interpreting services in the courts’.

The mismatch, the committee continued, suggests that ‘significant issues with court interpreting may be missed in the data the MoJ gathers, making it difficult for the MoJ or parliament to assess the scale and impact of problems in this system and the impact of these problems on access to justice’.

The committee noted that in 2024, over 5,000 requests for language services in courts went unfilled. It added: ‘Many failures are not officially recorded as complaints.’

Interpreters who provide their services through thebigword took strike action in 2024 and 2025. Grievances included inadequate rates, not receiving payments to which they were entitled and being required to cover multiple cases for no additional cash.

On behalf of its members, the National Register of Public Service Interpreters published a statement: ‘As long as bookings continue to be outsourced by agencies at inadequate rates offered to qualified and regulated interpreters, the current backlog… will continue growing.’

The Lords committee recommended the MoJ halt the procurement process for a new interpreting services contract, due to complete later this year. The department has rebuffed the plea.

A spokesperson for thebigword tells the Gazette: ‘Our priority is delivering a high-quality, value-for-money interpreting service that helps courts function effectively and ensures access to justice. We greatly value the professionalism of our interpreters who are at the heart of what we do and we constantly review performance to look for ways of strengthening the service.’

Clarion UK Ltd was approached for comment.

Waiting for a ride

The Gazette has been told about persistent problems with prisoner transport to the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey. This includes entire morning hearings being lost due to late delivery of prisoners. Frustrated practitioners also point out that it is not satisfactory for prisoners to simply arrive for a start time of 10am. Prisoners need to be at court in time to meet with their lawyers, who also need time to take their instructions.

The biggest problems relate to the magistrates’ courts – a particular concern in the context of the MoJ’s planned programme for reform (see below). Comments were provided on condition of anonymity.

‘It seems clear that to Serco, the Crown court takes priority,’ says one, who notes few delays in transport from the local remand prison to the Crown court just a mile away. ‘Perhaps they are bollocked more by Crown court judges.’

In magistrates’ courts in the same area, the prisoner transport issue is routinely dire, others add. ‘I’m Saturday court duty,’ says one practitioner, emailing me while they wait. ‘It’s now 10.10am and not one police station detainee is in court. These remands are expected at 10.40.’

‘For weekend cases on a Monday,’ says a solicitor, ‘it’s not unusual to have people not brought till Tuesday.’ Another relates ‘waiting at court till 1.30pm for two people from **** Custody Centre’.

‘There is a significant problem getting overnight remands from across [the county] to the magistrates’ court, where all first appearances in custody are held. This includes, for example, an accused refused bail,’ says another solicitor. ‘The vans seem to take a circuitous route and rarely arrive before 9.30am and often as late as 11.30am or noon.’

The courts referenced so far are serviced by Serco. In Wales, where GEOAmey is the PECS contractor, ‘there are significant issues with prisoners arriving late to court’, a criminal defence solicitor continues, ‘mainly in the magistrates’ court’. She adds: ‘Routinely, overnight prisoners don’t arrive till 11.30am or noon, which means that there is a delay in getting things started and [this] disrupts the court. Coupled with the delay in getting papers uploaded to the Common Platform, this means that despite being in court for 9am, we often can’t do anything till after lunch.’

On Monday, Kirsty Brimelow KC, a former chair of the Criminal Bar Association, highlighted the issue of delayed prisoner transport in her inaugural address as new bar chair.

‘The call for prisoner escort and custody service reform is the whine that became a roar,’ Brimelow said. ‘The combined value of the two contracts, for north and south, is nearly £1.4bn. The annual cost is around £138m. And yet hours are lost in courts each day due to prisoners not being brought to court on time and when at court, not taken up into the dock due to lack of staff.’

Read more

Counting and not counting

Where a problem applies to only 0.2-0.3% of cases, it should be hard work finding people involved in the process who describe problems as routine. In fact, it is incredibly easy. Not a single criminal law practitioner the Gazette contacted believes the MoJ figures on prisoner transport for trials are accurate. Trade unions who represent MoJ staff relate that the experience of their members is that this dismal picture holds true across England and Wales. Serious delays have been a feature of the service since it was outsourced, and have worsened.

So what is going on? Richard Miller, head of justice at the Law Society, explains: ‘There are a number of background issues that need to be understood about these delays and why they are not properly recorded.’ For example: ‘We understand that it is not counted as a “late arrival” if the prisoner is in a prison which is far from the court; they only count prisoners brought from the nearest prison.

‘At any one time, large numbers of prisoners are not in the prison closest to the court where their hearing is scheduled, so will frequently be late but not recorded as such. The crisis in prison accommodation has exacerbated this position.’

Miller adds: ‘Court legal advisers are supposed to complete “exception reports” when the defendant is brought late to court, however the practitioners say that they rarely do this as there is rarely any follow-up. Very little, if anything, appears to be being done to improve the situation.’

Andrew Bishop, consultant at Bishop & Light Solicitors and Law Society Council member for Sussex, says: ‘I understand that unless the court clerk completes a form and makes a formal complaint, then the lateness is not recorded. I have no doubt that only a small percentage of late arrivals are recorded, as it isn’t primarily the clerk’s problem. We are cross but rather resigned to it.’

‘I don’t think that the delays are being accounted for properly,’ is the view of Katy Hanson, chair of the Criminal Law Solicitors’ Association. She echoes Miller: ‘There is an issue in that if the prisoners are not in their local prison, then I don’t think [the PECS contractor] has to get them to court by a certain time. Due to the prisons all being full, this is happening more and more.’

So what?

Failings in outsourced criminal justice services have significant consequences, though, of course, they are contested by the contractor companies and the MoJ.

Take the welcome uplift in criminal defence practitioner remuneration. Announcing the government’s ‘swift and fair plan for justice’ on 2 December, justice ministers lauded the fact that ‘criminal legal aid advocates will get up to a £34m funding increase every year’. This ‘comes on top of an up to £92m per year boost for criminal solicitors confirmed earlier this week’.

The uplift is designed to stem the exodus of lawyers from publicly funded criminal defence work and attract more juniors to join their ranks. But the impact of the uplift will be blunted if delays exist and persist. Part of the financial challenge criminal defence lawyers, and/or their firms, currently face is that delays are not reflected in their fees. Delays also create a cashflow headache, as most solicitors are not paid until the conclusion of a case.

Lammy’s justice reforms, based on Leveson’s recommendations, are predicated on a substantial shift of criminal cases to the magistrates’ courts, and to a forum where a judge will sit alone. Yet the magistrates’ courts are the very forum from which the most serious and widespread reports of late prisoner transport emanate. Currently, the overcrowded prison estate, placing thousands of prisoners a day away from the court they must attend, gives transport services ‘a pass’.

Delays due to a lack of defence solicitor or counsel, counted as a cause of delay, may be due to the late delivery of a different prisoner to court. That is especially true where a duty solicitor is covering five or six cases at the magistrates’ court.

A question sits behind the critical issues raised by contributors to this article. Are Whitehall and the outsourced service companies it contracts with, too co-dependent? Does the success or failure of one define the other?

Justice ministers are quick to label so many elements of the criminal justice system as ‘broken’, and to attribute blame for the breakage.

Yet there is an unwillingness to question, based on negative feedback, the performance of outsourced services. This is evident in courts minister Sarah Sackman’s response to the review conducted by the Lords’ Public Services Committee into interpreter contracts.

Sackman is punctiliously polite in her correspondence. Yet her response to damning evidence gathered by the committee on the performance of the contracts, including a direct assertion that MoJ assessments must be at fault, is simply to double down on the virtue of the contracts and their operational performance.

But what if the Lords’ assessment is correct, and the real state of interpreter services in the courts is so dire as to threaten the very administration of justice?

And what if the stunning ease with which commonplace delays in prisoner transport are evidenced, especially for the magistrates’ courts, are correct, and the MoJ’s monitoring is at significant fault?

In that scenario, judge-only hearings will be delayed while a lonesome justice waits on the arrival of prisoners, an experience they will hold in common with the massed ranks of newly minted magistrates the ministry hopes to recruit.

In place of doubt on these points, the MoJ has certainty that its outsourcing arrangements are, as Sackman says of the interpreter contract, simply the best: ‘Outsourcing remains the best way to obtain these services as they allow us the ability to respond to changing … need and market expertise.’

No comments yet